The Biggest Success Story the Country Doesn’t Know About

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Over the last few weeks, an extraordinary series of events has altered the course of an election that previously seemed to have few surprises in store. Eight days after Donald Trump survived an assassination attempt, President Joe Biden announced his historic decision to withdraw from the presidential race and cast his support for Vice President Kamala Harris to run in his stead. It will be some time before we know all the political ramifications of these events, but whatever they may be, they will not change the past.

What can the past tell us about what’s to come? Perhaps the most critical element of a candidate’s platform is their approach to the economy. In assessing Harris as a presidential candidate, people will want to look at the economic track record of the Biden-Harris administration. As always, the president takes the lead role in setting the economic course for the administration, but throughout Biden’s term in office, Harris was standing alongside him. The Republicans will surely blame her for everything that went wrong and many things that didn’t. On the other hand, Harris can take credit for what went right, and there is much here to boast about. Indeed, she can (and should) run on the outstanding—and criminally underappreciated—economic record of the Biden administration.

Under Biden, the United States made a remarkable recovery from the pandemic recession. We have seen the longest run of below 4.0 percent unemployment in more than 70 years, even surpassing the long stretch during the 1960s boom. This period of low unemployment has led to rapid real wage growth at the lower end of the wage distribution, reversing much of the rise in wage inequality we have seen in the last four decades. It has been especially beneficial to the most disadvantaged groups in the labor market.

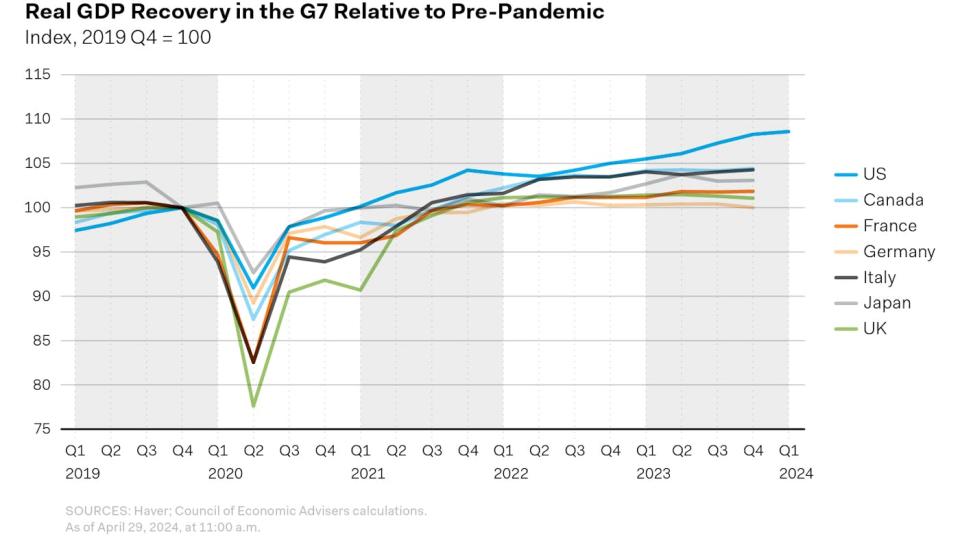

The burst of inflation that accompanied this growth was mostly an outcome of the pandemic and the invasion of Ukraine. All other wealthy countries saw comparable rises in inflation. As of summer 2024, the rate of inflation in the United States has fallen back almost to the Fed’s 2.0 percent target. Meanwhile, our growth has far surpassed that of our peers.

Furthermore, the Biden administration really does deserve credit for this extraordinary boom. Much of what happens under a president’s watch is beyond their control. However, the economic turnaround following the pandemic can be directly traced to Biden’s recovery package, along with his infrastructure bill, the CHIPS Act, and the Inflation Reduction Act, all of which have sustained growth even as the impact of the initial recovery package faded. While the CARES Act, pushed through when Trump was in office, provided essential support during the shutdown period, it was not sufficient to push through the recovery.

Finally, the negative assessment that voters routinely give the Biden administration on the economy seems more based on what they hear from the media or elsewhere. They generally rate their own financial situation positively and say that the economy in their city or state is doing well. It is only the national economy, of which they have no direct knowledge, that they rate poorly.

Let the Good Times Roll!

Before going through what is positive about the Biden economy, I’ll just state the obvious. Tens of millions of people are struggling to get by, or not getting by at all. This is a horrible situation, which we should be trying to change every way we can. However, this has always been the case. We have a badly underdeveloped system of social supports, so that people cannot count on getting the food, health care, and shelter they need.

It’s also the case that the spurt of inflation in 2021 and 2022 was a shock after a long period of low inflation. People found themselves paying considerably more for food, gas, shelter, and other essentials, and in many cases their pay did not keep up, especially at the time these prices were soaring.

But the Biden administration has taken important steps to directly improve the situation for low- and moderate-income people, notably by making the subsidies in the exchanges created by the Affordable Care Act, or ACA, more generous and expanding the Child Tax Credit, or CTC. He increased the benefits in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, or SNAP, by 21 percent. Unfortunately, the expansion of the CTC, which was included in the initial recovery package, was only temporary. It expired at the end of 2021, and Biden has been unable to get the support needed in Congress to extend it.

While we should always recognize the enormous work left to be done, we need as well to acknowledge when we are making progress, and we have made an enormous amount of progress in improving living standards during Biden’s presidency. Also, the suffering of tens of millions of people at the lower end of the income distribution can’t possibly be the explanation for negative views of the economy. People at the bottom were suffering at least as much in 2019, when most people gave the economy high marks.

And it is important to note two big Biden administration victories in expanding the welfare state. His enhanced subsidies in the ACA have led to a substantial reduction in the uninsured population. The number of uninsured was down by more than three million in 2022 (the most recent data available) from 2019, a drop of more than 10 per-cent. It had risen by more than two million under Donald Trump.

The other big Biden victory came in reducing the burden of student debt. Although the Supreme Court blocked his major debt forgiveness package, he has reduced or canceled the debt of almost five million people. These are mostly victims of for-profit scam colleges or people who had largely met terms of prior forgiveness programs but were thrown out due to paperwork mess-ups.

More importantly, he made the Clinton-era income-driven repayment plan far more generous, so that paying back student loans should not be a serious burden for most borrowers. A single person earning $32,000 a year now pays nothing, and a person earning $40,000 would pay just $60 a month. Unfortunately, this plan is not widely known by many, including people who write on the topic for major news outlets, but a Republican court challenge is at least now helping to call attention to the plan.

The Biden administration has made important improvements to the system of social supports, but he has been severely limited by what he could persuade Congress to do, even when the Democrats controlled both chambers. Lyndon Johnson was able to get the big Great Society programs passed because he had supermajorities following the 1964 elections. Until we see a decisive political shift, progress will have to take the form of incremental, but important, measures along the lines Biden put in place.

The American Rescue Plan

Just as President Barack Obama faced an economic crisis when he took office, and rushed through a stimulus, Biden also faced a crisis. Obama went in with a modest package, due to both political constraints and concerns about the deficit. The result was a slow recovery, with the economy taking a decade to get back to full employment.

Biden seemed determined not to repeat this mistake, proposing a $1.9 trillion (3.9 percent of GDP) package to be disbursed over two years. This included a number of items to protect people against the impact of the pandemic, such as enhanced unemployment benefits and the $1,400 stimulus checks he promised in the campaign, which helped get two Democrats elected to the Senate in Georgia.

In addition to the expansion of the CTC, it included funding to make the subsidies for the ACA exchanges considerably more generous. A family of four, earning $45,000 a year, can now get a standard insurance plan at no cost in the exchanges. At an income of $60,000, they would pay just $1,200 a year. It also provided hundreds of billions of dollars to help states deal with pandemic-related problems, like improving ventilation in public schools and distributing vaccines.

In addition to addressing immediate needs, the money was supposed to kick-start the economy, and it did. It is not generally recognized that job growth had slowed to a crawl in the period just before Biden took over.

There had been a huge bounce back in employment over the summer of 2020, following the spring shutdown, but job growth averaged just 140,000 a month in the last three months of the Trump administration. At that pace, it would have taken us five and a half years to get back the jobs we lost in the pandemic. Thanks to Biden’s recovery package, we got the jobs back in less than a year and half.

Click here for a sampling of innovative projects made possible by the Biden legislative wins

In the two years after the American Rescue Plan, or ARP, was passed, the economy generated almost 11 million jobs, an average of more than 450,000 a month. The unemployment rate had fallen to 3.9 percent by the end of 2021. It ticked up to 4 percent in January 2022, but then fell back below 4 percent the following month. It had been below 4.0 percent, until it just crossed over to 4.1 percent in June. (It was 3.96 percent in May, which is still below 4.0 percent.) This is the longest streak of below 4.0 percent unemployment in more than 70 years.

It is important to emphasize that the ARP was entirely Biden’s work. Not a single Republican in either house of Congress voted for it. And he got enormous pushback even from Democrats. Most notably, Larry Summers, a top official in both the Clinton and Obama administrations, pronounced the ARP the most reckless macroeconomic policy in 40 years. This complaint was echoed endlessly in the media.

Biden could have easily opted to go smaller and taken less heat. But he and his economic team recognized the mistake of the Obama administration: that it didn’t go big enough in responding to crisis. Team Biden was determined not to make the same error.

The Benefits of Full Employment

Many of us have long extolled the benefits of full employment. In a society where most people get most of their income from their jobs, being able to get a job is a really big deal. Also, a tight labor market gives workers, especially those at the lower end of the wage distribution, more bargaining power to push for better pay and working conditions.

Before going into this issue further, we should clear up a major source of confusion about unemployment and the labor market. Many people have trivialized the benefits of low unemployment, arguing that a 1 to 2 percentage point difference in the unemployment rate affects only two to three million workers.

This argument seriously misunderstands the nature of the labor market. In a normal economy, more than 5.5 million workers lose or leave their jobs every month (roughly 60 percent are voluntary quits), with the vast majority looking for new ones. This implies that nearly 70 million people are looking for jobs over the course of a year, although some do change jobs more than once. This means a very large share of the workforce is directly concerned with the strength of the labor market.

We saw this story play out in a big way in the recovery from the pandemic. The quit rate—the number of people who quit their jobs in any given month—soared over the course of 2021 and into the spring of 2022, hitting record highs. In the healthy pre-pandemic labor market, we saw around 3.5 million people quit their jobs in an average month. We crossed 4.5 million at peak quitting in April 2022.

While the news reporting was filled with gloomy stories about employers being unable to find workers, the much happier—and far less widely reported—flip side of this was that workers, including those at the bottom rung of the pay ladder, gained unprecedented market power. These workers had the ability to quit jobs that paid poorly, had bad working conditions, offered limited opportunities for advancement, or where the boss was a jerk.

The result was that the huge burst of job shifting did allow tens of millions of workers to end up in better jobs. The Conference Board’s survey on workers’ self-described level of workplace satisfaction hit a record high in 2023. Since workers spend much of their waking life at their workplace, this is a big deal.

Worth noting in this respect are the additional 19 million workers who are now able to work from home. The shift to remote work was a necessity in the pandemic, as many businesses could not operate normally. However, as vaccines became widely available and the situation normalized, many employers wanted to force workers back into the office. But the strong labor market meant that millions of workers were able to resist this demand. As a result, they are saving hundreds of hours a year in commuting time, and thousands of dollars a year in commuting-related expenses. While those able to work from home tend to be better-off workers, an increase of 19 million has to stretch well beyond a small elite. The benefits to this group—they’re saving money on commuting and spending more valuable time with their families—is a remarkably underreported story of the recovery.

We also have seen a huge uptick in new business formation. The Commerce Department reports that new business applications are up more than 30 percent from the pre-pandemic level. Applications of businesses with a high propensity to have a payroll have risen even more sharply. Those starting new businesses are disproportionately women, and especially Black and Hispanic women.

Other benefits of full employment came through as promised by those who have championed it. The unemployment rate for Black Americans hit a record low of 4.8 percent in April 2023, with the ratio of Black to white unemployment hitting its lowest level on record. The unemployment rate for Black teens hit an all-time low of 10.0 percent in the summer of 2021. The unemployment rate for Latinos tied a record low of 3.9 percent in 2022.

These numbers are still too high, and we have far to go to eliminate the effects of discrimination in the labor market. But we have seen serious gains as a result of the ARP.

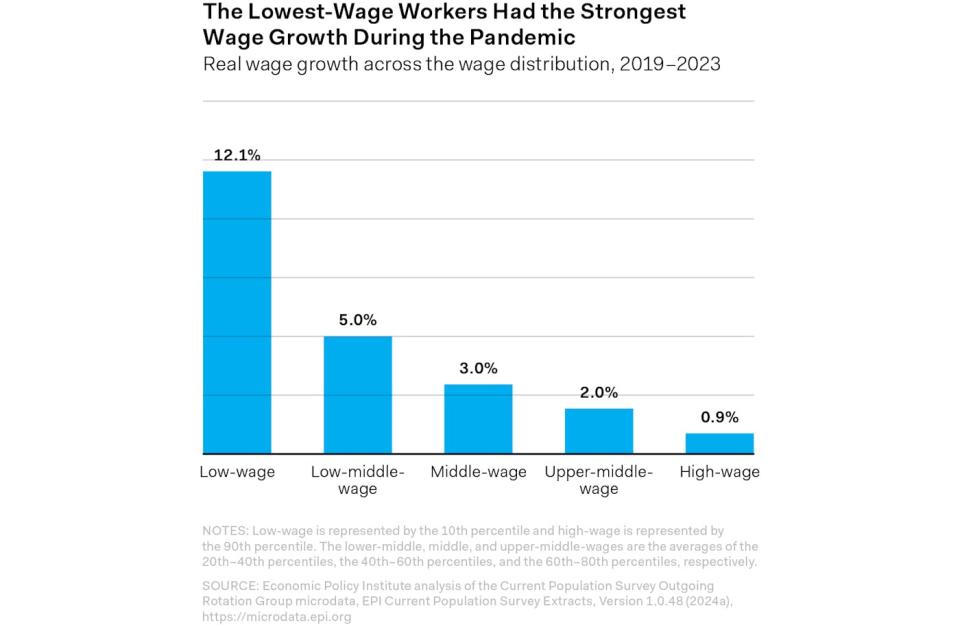

We have seen very impressive wage growth at the lower end of the labor market. A recent paper by Arindrajit Dube, David Autor, and Annie McGrew found that much of the wage inequality built up over the prior four decades was reversed in the recovery from the pandemic.

An analysis by Elise Gould and Katherine deCourcy of the Economic Policy Institute showed workers in the bottom decile getting real wage gains of 12.1 percent since 2019. Workers in the second-lowest quintile saw real wage gains of 5.0 percent. Given decades of stagnant or declining real wages, this is a big deal.

The Real Inflation Story

As we all know, we have seen the largest spike in inflation in more than four decades. This was bad news, but it was inevitable after the pandemic, which disrupted economies all over the world, reducing production in many areas. It also led to a huge increase in demand for goods, as people unable to spend their money on travel, restaurants, and other services instead looked to buy cars, computers, and refrigerators. This led to the massive supply-chain problems that featured prominently in news stories in the first two years of Biden’s presidency.

The impact of the pandemic was compounded by the fallout from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. This sent oil and gas prices soaring, in addition to the price of the grains that Ukraine was at least temporarily unable to export.

That was the bad news part of the story, but the good news is that we are clearly not seeing spiraling inflation of the sort that people like Larry Summers warned about. Inflation by many measures has fallen back to nearly its pre-pandemic rate.

Over the last year, the inflation rate in the Consumer Price Index, excluding owners’ equivalent rent, was 2.4 percent as of May. That compares to 2.2 percent in January 2020 before the pandemic hit. Pulling out OER is not just a cheap trick to make the numbers look better. OER is supposed to measure the rent that homeowners would be paying on the house they live in if they rented it. It is literally paid by no one, so excluding it from a measure of inflation does not seem unreasonable.

We also know that inflation in the OER category and the index for regular rent, which is 5.4, will be headed sharply lower in the months ahead. Indexes that measure the rents on units that change hands are showing sharply lower rents.

The CPI rental indexes are high now because they’re based on leases signed one or more years ago. When these leases are up for renewal, they will show much lower increases, and many may report declines. As these new leases get incorporated in the CPI, the inflation shown in its rental indexes will fall sharply, possibly to near zero. Instead of being a factor pushing up the overall inflation rate, rent may be a factor pulling it down.

Apart from the measurement issues, it is important to realize that we are not seeing a story of higher inflation expectations, which was a central feature of the wage-price spiral we saw in the 1970s. Expectations of inflation did rise modestly earlier in the recovery, but by many measures they are back to, or at least very close to, the inflation expectations people had before the pandemic.

Inflation had remained moderate under Trump, before plunging in 2020 with the start of the pandemic. When the economy shut down in March, demand for many items collapsed. Gas was selling for less than $2.00 a gallon as GDP plummeted and unemployment reached close to 20 percent. The cheap gas during the pandemic can make an effective political talking point, but it’s unlikely many would consider it a good trade to shut down the economy and be stuck in your house to save $1.50 or so on a gallon of gas.

Biden’s Big Three Bills: Infrastructure, CHIPS, and IRA

In addition to the ARP, Biden managed to get three major economic packages through Congress. In the fall of 2021, Biden got Congress to approve a bipartisan infrastructure package. The bill provided $1.2 trillion (2 percent of federal spending) for maintaining and improving infrastructure. While Trump had repeatedly tried to push infrastructure, he never produced a bill that came close to passing.

In addition to the standard bridges and roads infrastructure, this bill included funding for replacing lead pipes to ensure safe drinking water, spreading internet access to currently underserved areas, and building a nationwide network of charging stations for electric vehicles.

The CHIPS and Science Act was the second bill, passed in the summer of 2022. This was a package of incentives and research spending designed to put the United States at the forefront in the production of cutting-edge semiconductors. It addresses our current dependence on foreign suppliers, most notably Taiwan. The package is projected to cost $80 billion (0.1 percent of the federal budget) over the next decade.

The third package was the Inflation Reduction Act, or IRA, which Biden managed to get through that summer. This provided an array of subsidies and direct payments to support the transition to a green economy, as well as tax measures to cover the cost.

Given the chaotic situation Biden faced in trying to push legislation through an almost evenly divided Congress, it would be hard to imagine that he had planned the timing of these three big bills. But if he had planned the timing, he could hardly have done better than the way it turned out.

As it stands, the spending from these measures is kicking in just as the boost from the ARP is waning. This is not only on the government-spending side, but more importantly in the private sector. These measures are having exactly the impact intended.

This is seen most clearly with factory construction. This began to soar almost immediately after these bills were passed, as companies rushed to build factories for making advanced computer CHIPS, electric cars, solar panels, and batteries. Real spending on factory construction was almost 74 percent higher in the fourth quarter of 2023 than it had been in the fourth quarter of 2022. It was almost twice the level of the fourth quarter of 2019, the last full quarter before the pandemic.

By contrast, factory construction was pretty much flat under Trump even before the pandemic. It was almost exactly the same in the fourth quarter of 2019 as it was in the first quarter of 2017. (It fell sharply in 2020, after the pandemic hit.) This is a bit ironic, given the importance Trump had attached to manufacturing in his 2016 campaign.

The impact on sales of electric vehicles and wind and solar installation is also very clear in the data. EV sales increased 60 percent from 2022 to 2023. They are expected to rise further in 2024, albeit at a far slower pace. Installation of solar power generation capacity was 51 percent higher in 2023 than in 2022. The installation of wind energy capacity did slow somewhat in 2023, but this followed two years of rapid growth.

There have been issues with the implementation of these bills. There has to be far more progress in building power transmission capacity, which is being blocked by an array of regulatory hurdles. Also, U.S. auto manufacturers have not been as successful in producing high-quality electric vehicles as they originally hoped.

But we have turned a corner whereby clean energy is now completely cost competitive with fossil fuels, and EVs can compete with gas-powered cars. The United States is late to the game in getting serious about combating climate change, but thanks to these bills, it is at least in the game. Major companies, with profits on the line, will now be fighting alongside environmentalists to hasten the green transition.

It’s worth a quick mention of Biden’s alleged turn away from free-market fundamentalism to “industrial policy” with these major bills. This mischaracterizes the nature of economic policy.

We always shape policy to favor certain sectors. The most obvious example is the pharmaceutical industry. The U.S. government will spend well over $50 billion (0.8 percent of the budget) on biomedical research this year, through the National Institutes of Health and other government agencies. During the last half-century, the government has benefited manufacturers by making drug patents and related protections longer and stronger. We will pay well over $600 billion this year for drugs that would likely cost us less than $100 billion in a free market without these protections. Administrations of both parties have made the imposition of these protections on other countries a central focus of every major trade pact during this period. If that is not industrial policy, the term has no meaning.

We can argue about what constitutes good industrial policy, and Biden has taken a sharply different, and far better, path here than prior administrations. But a decision to favor certain sectors, implicitly at the expense of other sectors, is not a departure from past practice.

In addition to the spending side in these bills, the tax provisions of the IRA are a big deal. The Trump administration and prior Republican Congresses had gutted the IRS’s enforcement capacities to the point that for many rich people and corporations, taxes were optional. The IRA sought to reverse this trend by restoring funding for enforcement. This is a major change for the better, both in getting revenue for the government and in maintaining respect for the law. If the very rich can get away without paying their taxes, it’s hard to argue that anyone else should.

The other big revenue feature of the IRA was a tax on share buybacks. In the last four decades, corporations have increasingly used buybacks rather than dividends as a way to pay out money to shareholders. The buyback tax is a backdoor way to increase the tax on corporate profits. It also puts a big foot in the door toward shifting the basis for the corporate income tax from profits to returns to shareholders.

The big advantage of this sort of shift is that returns to shareholders (capital gains plus dividends) are fully transparent and can be obtained from any financial website. By contrast, corporate accountants tell us what corporate profits are. This switch can ensure we get the intended revenue from the corporate income tax and put the tax-gaming industry out of business.

As it turns out, we have already seen a dividend from increased enforcement. In 2019, corporations paid just 12.0 percent of their profits in tax. In 2023, they paid almost 18.0 percent of their profits in taxes.

The Path Going Forward

While Biden got several important pieces of legislation through Congress, he has seen others blocked. However, his administration has also used executive authority in many areas that will likely produce dividends in future years.

At the top of this list is appointing people at the Federal Trade Commission and the key positions in the Justice Department who take antitrust policy seriously. Ever since the Carter presidency, administrations of both parties have largely looked the other way as major companies bought up rivals and increased consolidation in important sectors of the economy.

Biden has reversed this, most notably by putting Lina Khan, a leading scholar of antitrust policy, in charge of the FTC. In this role, Khan has challenged a number of major mergers, as well as long-standing business practices like the filing of dubious patents by drug companies to block competition.

The payoffs from having a serious antitrust policy in place will mostly be felt over time, but the days when companies assumed any merger would just go through unchallenged are over. Perhaps most noteworthy on the list of challenged mergers is the proposed linking of Albertsons and Kroger, the country’s two largest supermarket chains. While most of the story of inflation since the pandemic involved supply-chain issues, some of it is due to higher profit margins. It is a safe bet that if this merger goes through, many of us will be paying higher prices for our food in the future.

The Biden administration has also taken direct steps to limit or end some of the most abusive practices of corporate America, such as junk fees associated with air travel or hotel stays. Biden has attempted to limit credit card late fees and other nuisance charges that are disproportionately borne by low- and moderate-income households. The administration got authority in the IRA to negotiate the price that Medicare pays for a number of important drugs. This will translate into billions of dollars of savings each year. Biden also capped the price that seniors pay for insulin.

In a similar vein, the Biden administration has arguably been the most pro-union since FDR. Biden took the unprecedented step of walking a picket line during the United Auto Workers’ successful strike last fall. He has appointed solidly pro-labor people to the National Labor Relations Board. This can have a large effect over time, but laws and corporate practices have become hugely tilted against labor over the last half-century, so reversing course will not be easy. However, big contracts won by the UAW, the Teamsters with UPS, and several other major unions provide a serious basis for optimism, as do the organizing drives at Starbucks and other highly visible retailers. If Democrats keep the White House, we can look for real progress in rebuilding the power of organized labor.

There is also some evidence that we are seeing a productivity upturn. This is a tough one to call, since the productivity data is enormously erratic and subject to large revisions; however, in the last year, productivity grew 2.9 percent, compared to a rate of less than 1.1 percent in the decade prior to the pandemic.

It is likely that the labor shortages following the pandemic forced many businesses to find ways to do things more efficiently. Also, AI should allow for large productivity gains in many areas, although it is unlikely that we have seen much impact yet.

In any case, productivity is a huge deal; if we can sustain more rapid growth, it allows for larger gains in real wages and living standards. More rapid productivity growth would also mean that we have less basis for concerns about inflation or the rising interest burden of the debt. It would make it easier to afford expansion of the welfare state in areas like free college or improving and extending Medicare.

We Can Tell People the Economy Is Good

In May, The Washington Post ran an editorial headlined “Telling Americans the Economy is Good Won’t Work.” Telling people that they are better off than they think they are would of course be foolish. But that is not the issue. For the most part, people actually think that they themselves are doing reasonably well, as this editorial notes. It’s just that for some reason, they think that everyone else is doing awful.

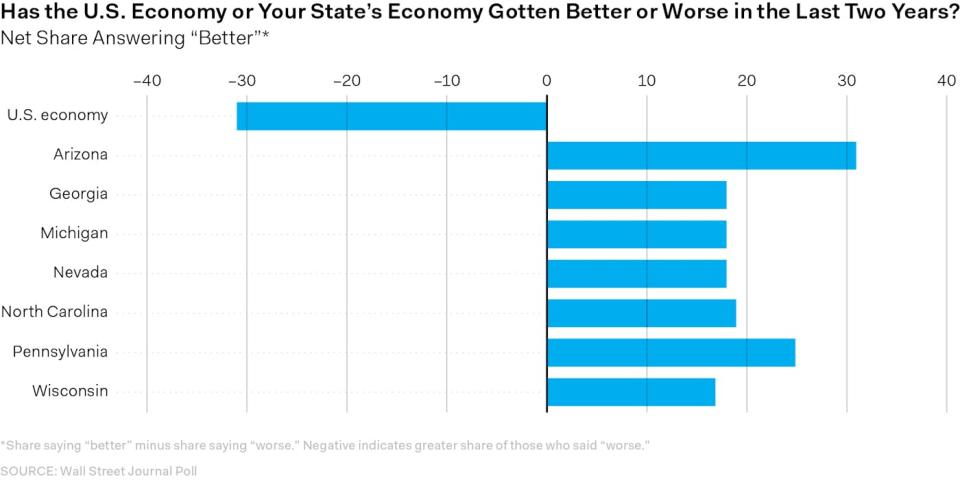

This becomes even clearer when we look at their assessments of their state economy as opposed to the national economy. A recent Wall Street Journal poll found that people in the seven swing states overwhelmingly thought the economies in their states were improving. Yet, by a margin of more than 30 points, they said the national economy was getting worse.

People do not have direct knowledge of the national economy apart from their own experience and what they see around them in their local economy. If they think the national economy is doing much worse than their state economy, it must be because of things they have heard, not what they directly experience and see. And we can see how that might work, even for people who don’t watch Fox News.

For example, CNN decided to highlight the retirement crisis at a time when the wealth of near-retirees was more than 45 percent higher than before the pandemic. And we keep hearing about young people never being able to own a home, even though ownership rates for the young are still above pre-pandemic levels. And The New York Times just told us recent college grads can’t find jobs, when in fact their unemployment rate is near a two-decade low.

We rarely hear about the 19 million additional people working from home, saving hundreds of hours and thousands of dollars a year on commuting costs. We also don’t hear about the 14 million homeowners saving thousands a year on interest from refinancing mortgages between 2020 and 2022. And we don’t see stories about record levels of workplace satisfaction.

The media have taken every opportunity to exaggerate or even invent bad news about the economy, while largely ignoring the positives. When the endless repetition of bad news gets amplified in social media outlets like X/Twitter and TikTok, it is not surprising that most people would have negative views of the economy.

When we tell people that the economy is good, it is this disinformation that we are contradicting, not people’s own experience of their economic situation. The Washington Post may not want us to do that, but there is every reason in the world to think that we should.

As a useful benchmark in this discussion, we should acknowledge the fact that if we had the exact same economy and Donald Trump was in the White House, he would be constantly saying “GREATEST ECONOMY EVER!” Every Republican politician and pundit in the country would be repeating this line. And the media would likely be telling us how the strong economy will make it difficult to defeat Trump in November.

It is important that people rely on the facts about the economy and not what the media tell them to think and say. The Biden economy is damn good by any measure, and he deserves credit for it. That’s the real deal.