A car crash killed a cyclist grandfather on a Sacramento road with an unprotected bike lane

Sau Voong, a vibrant former farmworker who raised a close-knit family in Sacramento and relished every opportunity to sport a leather jacket, was hit by a car and killed in Natomas Park on his morning bike ride June 11. He was 84.

The youngest of Voong’s eight children, Kwan, said that when her father was hit, he was riding south on Banfield Drive in the crosswalk at Club Center Drive, headed home. Voong usually rode his bike on sidewalks at the insistence of his family, said one of his granddaughters, Amanda, 31.

While he did have a car, he rarely drove, preferring to walk or cycle for the exercise. His children and grandchildren would frequently spot him pedaling around Natomas.

The Sacramento Police Department did not release much information about the circumstances that led to Voong’s death at the four-way stop in a residential neighborhood. His family said he was found on Club Center Drive, east of Banfield.

In the area of the crash, the law is inconsistently observed: On a recent Wednesday between 10:21 and 10:28 a.m., 22 vehicles passed through the intersection, and 15 of the drivers made an incomplete stop just a few hundred feet away from a small memorial to the great-grandfather and cyclist.

“Some intersections here are very busy, especially in areas that open up to the big roads,” said one of his daughters-in-law, Chelsea Wong, who is married to his son, Tony Wong. Voong was hit a block away from the large intersection of Club Center and Natomas Boulevard, a major thoroughfare. At that crossroads, a teenage cyclist and two drivers were severely injured in 2017 and 2019.

Chelsea said she hoped that officials would make safety improvements to the intersection, adding that traffic deaths were “an alarming warning to the city.”

The vast majority of dangerous car crashes are preventable with changes to road infrastructure, and Sacramento leaders have made a “Vision Zero” pledge to eliminate all traffic fatalities and serious injuries by 2027. Though the city has made some improvements, it remains far from the goal.

The capital region was just named the 20th-deadliest metropolitan area for pedestrians in the U.S., and Consumer Affairs reported in June that Sacramento has the most deadly crashes per capita of any large city in California.

The Sacramento Bee has reported on 11 other pedestrians and cyclists who have died this year: Mattie Nicholson, 56, Kate Johnston, 55, Jeffrey Blain, 59, Aaron Ward, 40, Sam Dent, 41, Terry Lane, 55, David Rink, 51, Tyler Vandehei, 32, James C. Lind, 54, and — in the nine hours before Voong’s crash — Jose Valladolid Ramirez, 36, and Larry Winters, 76.

After Voong’s death, Councilwoman Lisa Kaplan, who represents Natomas, called for a bond to fund more safety enhancements.

How speed kills and hood height kill

Police said that the driver who hit Voong was in a 2022 Toyota RAV4. With a hood height of about 40 inches, the SUV is deadlier to people around it. According to a study of nearly 18,000 pedestrian crashes by the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety, vehicles with hood heights greater than 40 inches — compared to cars with a hood height of 30 inches are less — are 45% more likely to kill a pedestrian in a crash.

In Sacramento, these more-lethal cars are expressly permitted to travel at lethal speeds. A study in Accident Analysis and Prevention found that when a vehicle strikes a pedestrian at 24.1 mph, that average risk that the pedestrian will die is 10%, and at 32.5 mph, the average risk that the pedestrian will die jumps to 25%.

The speed limit on Club Center, which has unprotected bike lanes and winds through a residential neighborhood, is 35 mph.

Speed bumps west of Banfield slow down cars, but to the east, nothing forces drivers to reduce their speed. A Sacramento Bee reporter spent 10 minutes standing 200 feet east of Banfield on a recent Wednesday with a small speed radar gun. Between 10:35 and 11:45 a.m., 15 westbound vehicles approached the stop sign with a median speed of 24 mph — already a risky speed made more dangerous when the vehicle is larger.

And while the investigation into Voong’s death remains ongoing, his large family has been left feeling as though his final years were stolen. They were already in mourning: The crash happened just three months after the death of Bat Su, Voong’s wife of more than 60 years.

A huge, loving Sacramento family

Sau Ngan Voong was born Jan. 15, 1940, in the Guangxi region in southern China. He married Su when they were both young, and they farmed alongside each other. Their first child, a son they named Sang, was born March 25, 1961. The pair went on to have seven more children: four daughters — Cu, Joanna, Emily and Kwan — and three sons — Tony, Menh, and Yee.

In 1984, the couple immigrated to the California capital with all eight children. Their youngest, Kwan, was just 2; their oldest, Sang, was 22. Hoping their kids would have more opportunities in the U.S., they all squeezed into an apartment in south Sacramento, with Su’s brother serving as their immigration sponsor.

Voong and Su continued agricultural work in the Sacramento region to support their kids. It was, Kwan said, “very difficult.”

“Our parents, they tried to provide everything for us as much as possible. They were farmers: They worked day and night,” Kwan said. “As immigrant parents, they did a lot.”

Despite the hardships, the couple filled their home with love, and as adults, all of their children structured their lives to stay in Sacramento so they could remain close together

Voong’s daughter-in-law Chelsea began to cry this month as she described how warmly the patriarch had welcomed her into the family. She called him “father.” When Tony bought a house in Natomas around 2000, almost the entire family followed suit and relocated from south Sacramento to the northwest pocket of the city so they could live near each other.

In the mid-’90s, Voong retired. As the family resettled in Natomas, the couple moved in with two different children — Voong with Sang, and Su with Menh — so that they could better divide the work of caring for their many, many grandchildren. At the time of his death, Voong had almost 40 grandchildren and great-grandchildren, all of whom he had a hand in raising.

Though they slept in separate homes, the couple still spent most of their days together. And when Su was hospitalized in January, Voong was at her side all day, every day, said his granddaughter Amanda. The family group chat made sure he had a ride every morning, that the two of them always had a lunch companion, and that the grandfather had a ride home every night.

Su died March 13, and Voong was shaken by the loss. He had spent more than 60 years — his entire adulthood — with her. For a while, he seemed far from his normal self. In what would be the last few weeks of his life, he took solace in his routines: Calling his children. Tending his garden. Riding his bike.

Passing down traditions and a love of family

Voong instilled an appreciation for tradition through multiple generations. Though Voong and Su passed on hosting responsibilities to younger relatives in recent years, for a long time, the couple would make a huge Lunar New Year feast for the family. Voong would prepare his famous sweet and sour pork, and they’d splurge for shark fin soup. Su would do much of the prep work, and Voong would do much of the cooking.

Although most of the Voong family lives close by, there are so many of them that it is a logistical struggle to gather them all at once; on this holiday, though, “everyone,” Amanda said, “showed up.” For the last Lunar New Year, in February, the mood was a little different because Su was in the hospital. But still, Amanda said, laughing, it was “the same loud chaos.”

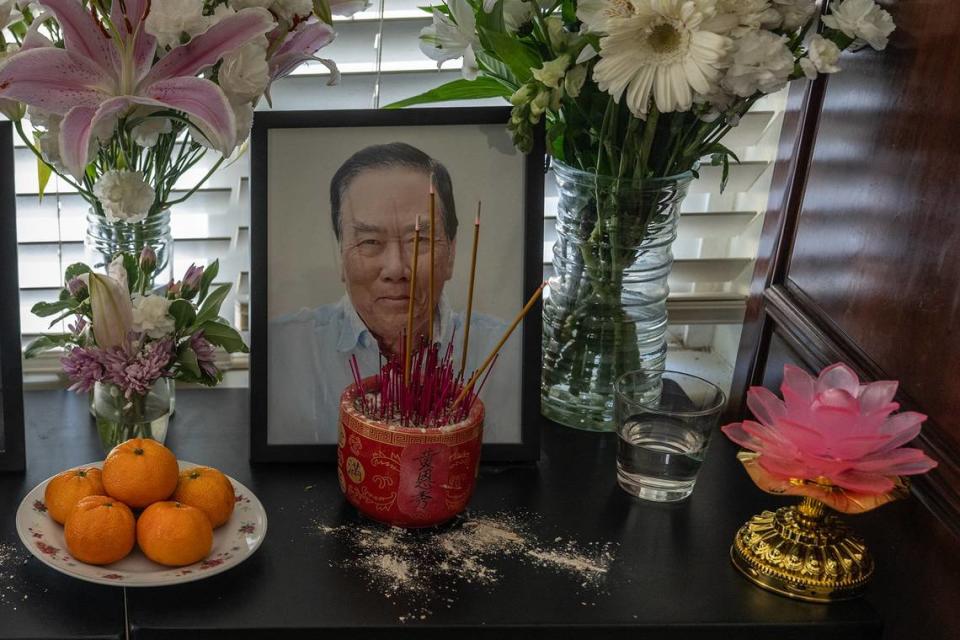

A large, ornate altar to the family’s ancestors stands in his son Menh’s home. Next to the altar, two small folding tables each hold a framed photograph: Bat Su and Sau Voong. They smile: Su’s hair gray, and Voong’s hair dyed black because he thought it looked sharper that way. Last Monday, Amanda lit one stick of incense for her grandfather, one for her grandmother, and two more for previous ancestors.

“This is what grandpa took care of,” Ken said, gesturing to the altar. “Generational stuff. This is our great-grandparents’, our great-great-grandparents’ stuff. They’re in there, watching over us, is what the blessing is.”

Voong insisted to his grandchildren, Ken said, that even his great-grandchildren should be close to one another. “He was big into family,” Ken said. He recalled his grandfather telling him “specifically” to “‘make sure they know each other.’”

Voong’s granddaughter, Jamie, 22, said she will take over caring for the fruit trees he and her grandmother planted in her parents’ backyard. Voong, who loved to make things grow even after his retirement from decades of farm work, cared for a stand of trees that included a nectarine tree, a peach tree, a fig tree, a persimmon tree, two small trees whose leaves he used for tea, as well as an herb garden and plants to ward off mosquitoes. He could be resourceful: Some of his garden was planted in buckets.

The garden is just a few blocks away from the street with the unprotected bike lane. On the side of the road, his children and grandchildren placed 10 votive candles, a small bowl for incense, a photo of Voong on vacation in Cozumel, and two miniature candy bars for the great-grandfather with a sweet tooth. A small handmade card wished him “happy father’s day” in a child’s handwriting — a message, the family thought, that should have been delivered in person.

Sau Ngan Voong

Great-grandfather, avid gardner and Natomas Park resident.

Age: 84.

Died: June 11, 2024. He was struck by a car at Banfield and Club Center drives as he headed home from his morning bike ride.

Survived by: Children Sang, Tony Wong, Menh, Cu, Yee, Johanna Delizo, Emily Cruz and Kwan, and dozens of grand- and great-grandchildren.