With false promises, Florida sent migrants to Sacramento a year ago. Where are they now?

On a recent sweltering June afternoon, Jorge Gil Laguna smiled as he walked into his shoddy motel to greet Olglaivis Barrios.

Markers of their last year in Sacramento surround the young Venezuelan couple. Heaps of donated clothes, shoes and purses in the corners. Barrios’ laptop, gifted to her last July, lay on the small dining room table. And a framed photo of a classic blue car, given to Laguna by a former employer, hung on the wall.

But in his hand, Laguna, 34, held their most important item yet: paperwork providing temporary protected status. The designation allows the Venezuelan to legally stay and work in the United States until April 2025.

“If I was working without one, imagine now,” Laguna said, before grinning. “It’s time to work like a donkey.”

This legal permit has the potential to provide stable work opportunities, allowing the couple to move out of this Rancho Cordova motel, where housing costs $72 a day. They also hope to send more money back to their three children and Barrios’ mother, who is caring for them in Venezuela.

Just more than a year ago, Laguna and Barrios, 29, doubted this day would come.

They were among the 36 Latin American migrants who unknowingly boarded planes for Sacramento and promised free housing, high-paying jobs and help with their immigration cases. Instead, the flights, under the direction of Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, left the migrants stranded in California and at the center of a political battle over immigration.

Their arrival elicited national headlines, public outrage from state officials and a community-wide response, largely shouldered by nonprofit and faith-based organizations. The attention eventually faded away and federal, state and county governments failed to provide resources. In this void, groups and volunteers have borne the unexpected costs of helping the migrants.

“If you look at where the time, resources and volunteers came from, it was local organizations figuring it out,” said Jessie Tientcheu, the CEO of Opening Doors, a nonprofit that provided some migrants with short-term housing.

Despite these challenges, members of the group are likely better positioned than most migrants who have entered the country in recent years. The organizations that provided stipends and free housing also emphasized the importance of building community relationships. So today, months after formal aid subsided, help finds those who chose Sacramento as their home.

“The support hasn’t really ended as a result of the fact that we’ve made friends among the group,” said Shireen Miles, a volunteer with Sacramento Area Congregations Together, the faith-based community organization that spearheaded support for the migrants. “And you don’t ever move on from your friends.”

‘Their new life here’

Most of the original 36 migrants, which included natives of Colombia, Mexico, Guatemala and Venezuela, have left the capital region. Some moved to bigger cities such as Los Angeles, San Diego and Chicago, while others sought out smaller states such as South Carolina and Tennessee.

They left for a host of reasons, including California’s high cost of living, lack of employment opportunities and personal connections in other locations, according to Gabby Trejo, executive director for Sacramento ACT.

Twelve members of the group remain in Sacramento — some sharing hotel rooms, others living for free at their work sites in Folsom and Rio Linda and a group of four splitting the costs of a townhouse in Rancho Cordova. By staying in the region, these members of the group benefit.

“They know that they’re not alone, and there’s this larger community that sees them and wants them to be successful in their new life here in the U.S.,” Trejo said.

Take Jose Castellanos, 34, and his wife Margarita Yanez, 35. They are a recently married Venezuelan couple expecting a child this December. The two migrants have not paid for housing since arriving in Sacramento.

“It’s been a help, a huge help, I’ve seen rents for $1,500,” said Castellanos, while shaking his head.

During the initial weeks, they slept at a church alongside the other migrants. Sacramento ACT transitioned the group to motel rooms in Rancho Cordova. The organization raised roughly $307,000 in donations and grants over the last year to assist the migrants.

When that funding dropped to low levels last October, Opening Doors, an organization specializing in resettlement, offered to house 17 of the migrants for up to six months.

Temporary housing is critical for asylum seekers, refugees or individuals in similar situations, said Tientcheu. In this case, the organization rented multi-room family homes to accommodate the migrants.

Nearly all of them left the housing before the six months was up.

“They usually just need a safe place to land for short periods of time so they can get their next steps in order,” Tientcheu said.

La Abeja, a newsletter written for and by California Latinos

Sign up here to receive our weekly newsletter centered around Latino issues in California.

Castellanos and Yanez found their next temporary home through Miles, who has grown close to many of the migrants in the last year through Sacramento ACT.

The migrants were introduced to Miles in the days following their arrival. She drove them to thrift stores for clothing, taught them how to use regional transit and showed them around Sacramento.

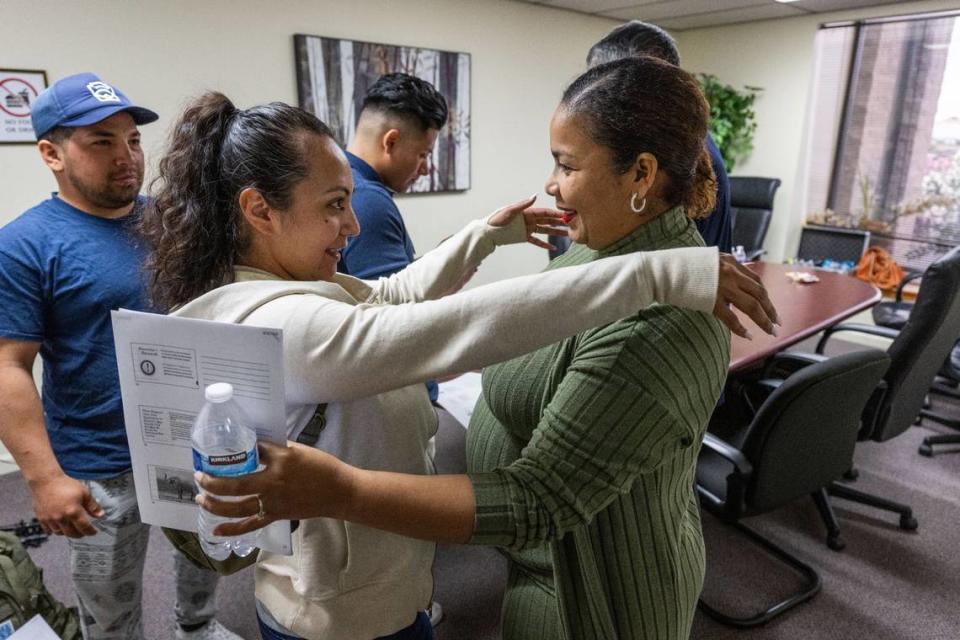

Even now, Miles sees some migrants a few times a week — driving them to immigration appointments or the DMV. She often starts her interactions with migrants with a firm hug.

“I have them calling me Tia (aunt),” Miles said.

‘I’m fine staying’

A year since they met, Miles considers Castellanos and Yanez her friends.

She was a witness to their wedding last October and invited them to her home to celebrate Christmas. When the couple needed a temporary place to stay, Miles introduced them to a friend who needed a house and dog sitter while traveling.

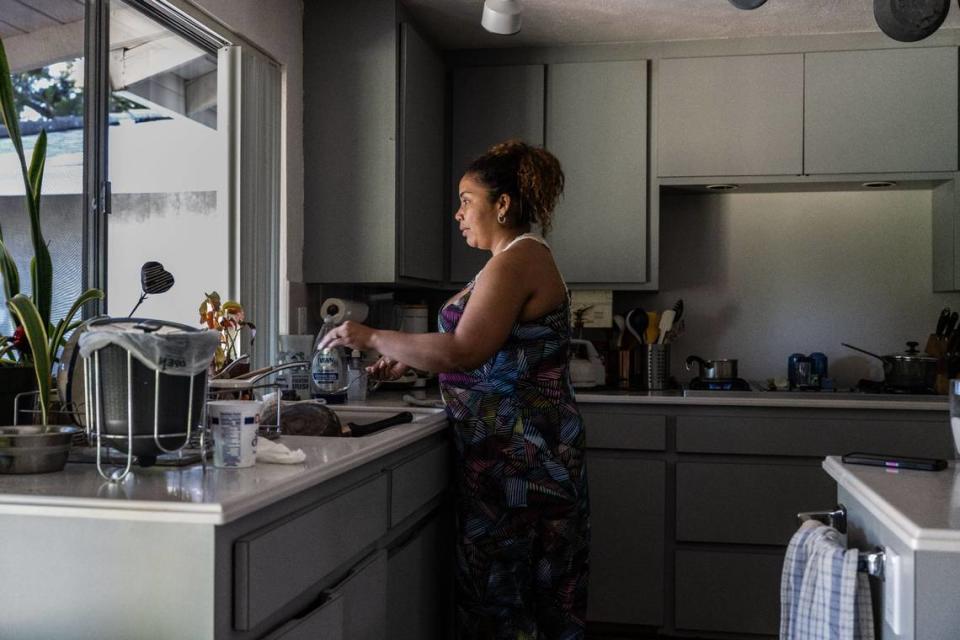

The Carmichael home offers peace for Yanez, who is nearly four months pregnant and dealing with ongoing headaches and vomiting. Most days, she’s alone cleaning the home while Castellanos works. Other times, Miles accompanies Yanez to her prenatal appointments.

Castellanos’ days have largely consisted of work since securing his temporary protected status in March. He is employed at a construction company Monday through Friday and also serves as a gardener for about a dozen homes in Sacramento. Occasionally, he picks up odd jobs such as moving around furniture or housekeeping.

“I’ve met many people (over the last year) and have the numbers of those people, so whenever they need a job done, I’m there,” Castellanos said.

His opposition to the current political Venezuelan regime influenced the couple’s decision to immigrate last year. Castellanos, who was in the country’s military, said he had an order for his capture by the government.

Their decision to return to Venezuela hinges on the administration.

“If the politics change, I’ll head back,” Castellanos said. “If not, I’m fine staying here.”

For now, Castellanos and Yanez are concentrating on their immigration cases. They have filed asylum cases and plan on exploring their options for a U visa, which opens eligibility for public benefits and creates a pathway for citizenship.

But that means more time away from their family. The two immigration options are often yearslong processes.

Regardless, the couple is willing to make that sacrifice. Both send money back to their children from previous relationships.

“We’ve been able to help our families so much,” said Yanez, who is a mother of four.

Still, much of their free time is spent on the phone with their family in Venezuela.

When he gets home from work, Castellanos said he will often spend hours on the phone with his 10-year-old son watching him play online games like Roblox or Minecraft. He doesn’t mind ending his busy days that way.

“I prefer he plays with me then with someone else,” Castellanos said.

‘Grateful for an opportunity’

The nightstand in Jorge Gil Laguna’s motel room proudly displays four muddy baseballs and a red number 28 jersey — presents from his new recreational team.

Laguna’s journey to joining the Redbirds began last month at Carmichael Park when he walked up to a group of older men practicing for their softball league. He wanted to play with them.

The men struggled to understand Laguna, until they called over Dionisio Holmes, the only Spanish speaker among them. But Holmes, who was born in Panama, couldn’t fully comprehend Laguna’s request. He is way too strong and young to play with this team, Holmes recalled thinking.

“We were a bunch of old guys,” Holmes, 70, said.

But Laguna was persistent.

Baseball has been his passion since he was 8 in Venezuela. Luck wasn’t in favor, however, he said. He and Barrios grew up poor and started working as teenagers.

“Food is more important than sports,” Barrios said,“so he couldn’t really focus on baseball as much as he would have liked.”

The couple met more than a decade ago on the beach of Barrios’ hometown. They came to the United States to provide a better life for their three sons aged 10, 11 and 13. Their goal is to make enough money and return to Venezuela, where they can perhaps buy a home or open a business.

“I don’t see a dream here,” Barrios said. “My dream is with my sons.”

Even with the obstacles, Laguna’s baseball talent is undeniable. He impressed the group of retirees within minutes of joining them last month by hitting ball after ball over the 300-foot fence.

“This kid got talent,” Holmes said. “He’s just not talking stuff. I could see it in his swing.”

Holmes committed to finding a league for Laguna, who promised that his pitching was better than his hitting.

“As a human being, you try to help people out,” Holmes said.

A few weeks later, Holmes drove Laguna to try out for the Sacramento Men’s Senior Baseball League.

Again, Laguna only needed minutes to impress the coaches and players with his pitches of nearly 90 miles an hour.

“You can’t pitch like that in California,” said Erik Guimont, a commissioner and player for the league. “That’s Texas heat.”

By the end of the half-hour showcase, it was decided: Laguna would pitch that upcoming Sunday for the Redbirds.

Be informed, engaged and empowered residents of Sacramento

Sign up here to receive our weekly newsletter centered around equity issues in the capital region.

In a conversation afterward, the coaches asked if he felt comfortable starting the game. He said “yes.” They asked if he could pitch at least 60 balls. He said “yes.” Then, they asked if he had gray pants. He said “no.”

Guimont provided him with an extra pair of his pants. Laguna promised to dedicate the game — his first time pitching in a baseball game in more than two years — to him.

“I’m grateful for an opportunity to play, especially here,” Laguna said. “There’s nothing else to do, but give it my best.”

‘Our family’s destiny forward’

Though migrants who came to Sacramento last year are grateful, some feel their counterparts are getting more help from nonprofit groups, such as for housing, than is fair.

“I understand it’s not their obligation, but they are helping others who arrived the same as us and in the same position as us,” Barrios said, referencing those individuals not paying for housing.

That perception, Trejo said, is incorrect. No migrant is still receiving formal help through any organization. Any support they receive is through connections that they made in the community.

But, she said, the viewpoint shouldn’t be dismissed. It is likely affected by a disillusionment of America.

These migrants, like millions of others who have crossed the border, came for the desire of a better life. When they arrive at the “promised land,” Trejo said, they quickly realize there is “no real strategy or process to receive support.”

“That must be really disappointing. … The systems are not designed to help immigrants be successful,” Trejo said.

To make matters worse, Miles said, the group’s first weeks in the country began with lies and confusion.

Individuals approached them outside a migrant center in El Paso, Texas promising plentiful work and housing. Days later, they arrived in Sacramento. The group was thrust into the national spotlight and met with California Gov. Gavin Newsom, Attorney General Rob Bonta and several organizations. All the meetings created an impression that more help would follow.

“It’s confusing for new migrants who think there’s this system that all works together,” Trejo said.

The group’s members also have “personality differences.” Miles said those distinctions influenced each migrant’s current situation.

“Some of them are really outgoing, really gracious. Even though there’s a language barrier, they’re still finding a way to express their appreciation and build those connections,” Miles said. “Others are quiet, shyer and that’s just human nature.”

For his part, Castellanos isn’t worried about the others in the group. He’s grateful for his Carmichael housing as long as it’s available. His focus is solely on his family’s future, not hesitating when asked about what he wants for his soon-to-be born child.

“To at least learn English,” he said, laughing alongside his wife.

But their laughter faded and Castellanos’ expression grew serious.

Above all, Castellanos hopes for a healthy baby. Beyond that, he has another wish.

“To push our family’s destiny forward.”