The site of the first free Black town in the U.S. is being rebuilt near St. Augustine

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

It all started as a term paper.

In the mid-1980s, then-University of Florida graduate student Jane Landers hit the archives to research something for a class assignment. There, she stumbled upon something rather unique: an Underground Railroad that went south to Florida as far back as 1687. Landers was baffled and knew the subject needed more “scholarly attention.”

“I care about what kids think of themselves and I don’t want every child to think their whole background is getting off barefoot from the slave ships,” Landers said. “There were all these other kinds of experiences; there were free people.”

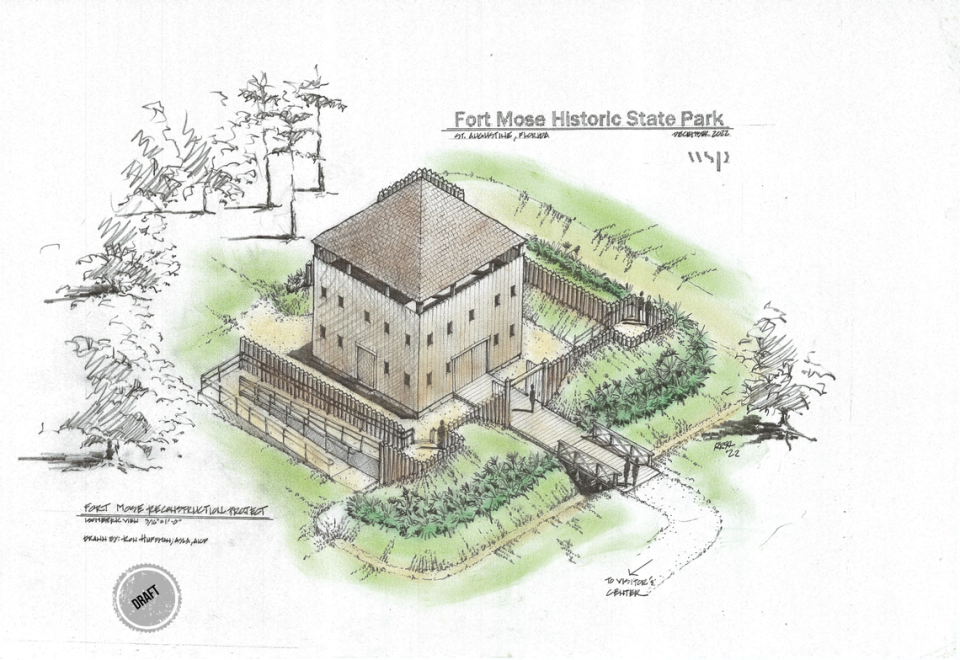

What Landers ultimately discovered was Gracia Real de Santa Teresa de Mose, better known as Fort Mose, the first town for free Black people in what would become the United States of America. Established in 1738, the town sat just a few miles north of St. Augustine, the oldest city in the country, until the Spanish sold Florida to the British in 1763. And while this history lay dormant for years until the mid-80s, its importance to not only Florida but this country will be enshrined forever once the reconstruction of the fort is finished in 2025.

“We decided to reconstruct the 1738 fort because that was the first site of freedom,” said Julia Gill Woodward, the CEO of the Florida State Parks Foundation, a nonprofit that’s helping to oversee Fort Mose’s resurrection.

Without Landers, the reconstruction might not be possible. It was Landers who brought the records she discovered to her UF professor Kathleen Deagan, an archaeologist who commissioned two digs on the site where remnants such as musket balls, ceramic wears and even a handmade medal were found. Soon after, Fort Mose became part of the Florida State Parks system, was added to the National Register of Historic Places and a museum was built on the site. In the years since, the Fort Mose Historical Society has worked to uplift the story through reenactments and events.

“They keep it alive,” Landers said. As for the reconstruction of Fort Mose, she was thrilled. “It helps tell the story. Not everybody will read my footnoted work but they’ll take their kids and their families to that place. It makes it more physically real if you have something that they can visit.”

Fort Mose arose during the colonial conflicts between England and Spain. Enslaved peoples, primarily from the English-owned plantations in the Carolinas, began to hear rumors that Spanish Florida provided a refuge from slavery. The first freedom seekers – eight men, two women and a three-year-old child – arrived in St. Augustine in 1687.

“People in search of freedom were doing it well before the Civil War,” said Chip Storey, a historian and board member of the Fort Mosey Historical Society.

As rumors spread, more and more enslaved people began to make the journey to Florida. The Spanish then saw an opportunity: in 1693, King Charles II issued a decree that all who fled to his territories and converted to Catholicism would be free. Spain’s somewhat different system of slavery – enslaved people could eventually gain their freedom unlike that of the English settlers who kept people in bondage for life – likely motivated this change as free Blacks had existed in Spanish society for quite some time, according to Landers.

“There was still legal slavery but there were all these legal routes to get out of slavery too: self-purchase, service to the military, owners can free you, baptism,” Landers added. “It wasn’t a closed system like the Anglo-Saxons. A different legal system, religious system and social system.”

By 1738, the Spanish governor of Florida chartered Fort Mose, which would become home to roughly 100 freedom seekers at its peak, as a defense system of sorts.

“Fort Mose was kind of a buffer for Spain,” said Marvin Dunn, the author of “A History of Florida: Through Black Eyes.”

And it worked. When the English raided Florida in 1740, it was a free Black militia, working alongside the Spanish and Native Americans, that squashed the attack in what became known as the Battle of Bloody Mose. The fort, however, suffered severe damage and the community abandoned it in favor of St. Augustine. In 1752, its former inhabitants rebuilt and returned to Fort Mose, where they stayed until the British purchased Florida.

“They established a successful community that was not entirely self-sustaining – they sometimes got assistance from the surrounding St. Augustine – but these people were working the land, scrounging for food and self-governing in the early 18th century,” Storey said.

Unwilling to return to their enslavement, many of the residents of Fort Mose would flee to Cuba. The military would occupy the fort itself until it was abandoned in the early 1800s. Fort Mose’s history remained hidden until Landers and Deagan who used NASA imagery to uncover the second fort as well as submerged fragments of the first.

Despite Fort Mose’s rather recent discovery, its importance to the story of this country cannot be overlooked.

Fort Mose shows “how desperate people were to gain freedom – going through these marshes where there were alligators and snakes and all the Florida fauna of the southeast which is in some ways more difficult to traverse than if you were going north to Canada,” Storey said. “The people wanted this and they were determined.”

“That was a community that thrived, survived and then was destroyed but the people there survived,” Dunn added. “The fort was wiped out but their legacy, their history, their presence in St. Augustine and other parts of Florida continued. They didn’t disappear.”

For information about Fort Mose visit https://fortmose.org/museum.