Is There a Good Reason Not to Panic? Well, No, Not Really.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

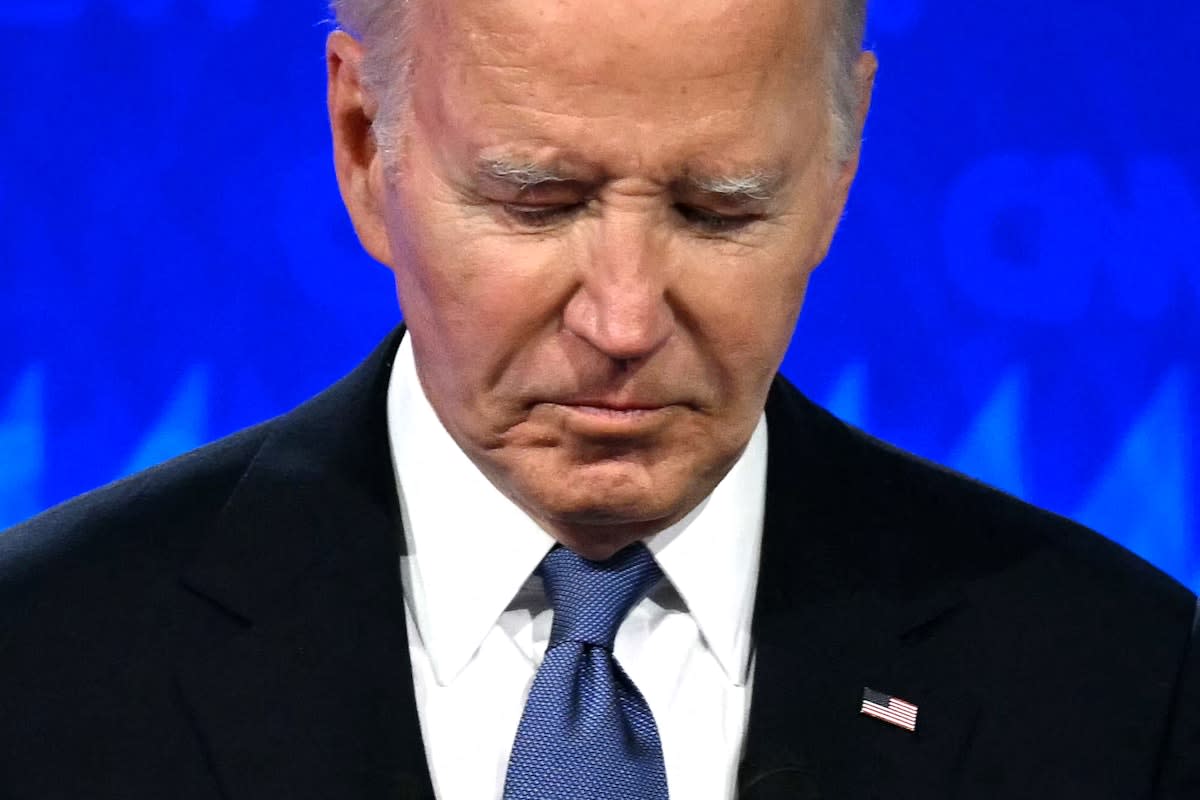

Joe Biden had barely opened his mouth last night when I gasped and said to myself, “Oh God, this might be really bad.” His voice was thin and raspy and weak. His words, ostensibly about how badly Donald Trump botched the pandemic, were unfocused and constituted a huge missed opportunity. And that kept happening over and over and over again.

Trump lied like crazy, sure. Nobody’s aborting a fetus after it’s born. “Everyone” did not want Roe overturned. Millions of people from prisons or mental institutions have not crossed the border. Food prices haven’t “quadrupled.” It went on and on—CNN’s fact-checker said he counted at least 30 outright lies. Jake Tapper and Dana Bash never stepped in to fact-check Trump. All that is true. But none of that changes the overwhelming fact. Biden confirmed Democrats’ worst nightmares. “We finally beat Medicare”? Dear God.

CNN’s flash poll had respondents saying Trump won by 67 to 33 percent. Frankly, I’m not sure who those 33 were. The die-hardest of die-hard Democrats, I guess, or maybe single-issue voters who heard Biden say one thing they liked. But 33 percent means a ton of Democrats admitted that their guy lost, and the guy they really hate and rightly consider a direct threat to the country won. And probably half of that 33 were voting with their heart.

What happens now? Let’s talk about the people who have the power to go to Biden and tell him to step aside. What kinds of conversations is Barack Obama having today? Who’s Chuck Schumer talking to? Hakeem Jeffries? Nancy Pelosi? How about Bill and Hillary Clinton, and Al Gore? The big donors and bundlers? And perhaps most of all, there’s Jill and his family.

All these people have known for a long time that the Democrats had three options. The first has been sticking with Biden. People knew he was a risky proposition. But until this debate, Biden was, plausibly, the least bad option. Because the other two options are these.

Option two is that Biden steps down and hands it to Kamala Harris. She’s his vice president, and how in the world do you sidestep a sitting vice president?

That’s the most likely non-Biden option, but I know no one who’s excited about it. She’s just not a good politician. What’s the scenario where she beats Trump? Maybe she generates some higher enthusiasm among Black women, and theoretically among younger voters to some extent. Maybe she’d have more success making the race a referendum on abortion.

Harris, though, has a huge weakness. She has never really been able to make a strong economic argument. Even back when people were gushing about her in early 2019, when she announced her presidential candidacy, I noticed she had nothing to say about economic issues. And they’re kind of important in a presidential election. And then, of course, there are the racism and sexism you have to factor in here that would hurt her unfairly. My guess is that she runs three to five points worse than Biden against Trump, and that turns a margin-of-error race into a decisive loss—and one that probably affects control of the House and/or Senate.

The final option, therefore, is to throw the thing open and try to get the nomination to one of the governors, or someone else. This has always had a lot of theoretical appeal, because several of these people look like they’d be good candidates.

But the two perceived problems with this scenario are these. First, how much bad blood would start boiling within the party if Harris were pushed aside? The assumed answer has always been: a lot. If Biden were to step aside, pollsters would start asking questions about Harris, and if those polls showed that Black women will basically bolt, going around Harris could be a nonstarter.

And second, is there really any proof that Gretchen Whitmer or Gavin Newsom or Josh Shapiro or Jay Pritzker or anyone else would be a better candidate? Governors sometimes just don’t have it when it comes to running for president. Look at Ron DeSantis.

Those are real problems. But in this break-glass moment, they start to look like smaller problems than staying with Biden or just handing it to Harris.

We’ll see what the post-debate polls say. They’ll start coming out early to mid-next week. My guess is that Biden will lose four points on average, maybe five. It might be a little less. But the coverage of this fiasco over the next two days will only amplify how bad it was.

Politicians fear the unknown. They don’t want to cast votes whose political fallouts they can’t predict. They don’t want their districts redrawn. And they sure don’t want to change a presidential candidate in July.

But this is an undeniable crisis. I don’t know the convention rules. And remember—this is made even more complicated by the fact that Democrats have decided to nominate Biden via Zoom (or whatever) two weeks before the mid-August convention, because they need to have a nominee by early August for the nominee to appear on the ballot in Ohio.

So: Is an abbreviated, multicandidate campaign even possible? Here’s a scenario. Biden drops out next week, releasing the delegates he’s amassed during the primaries to do whatever. Candidates announce—Harris, the governors I named above (along with a few others, like Kentucky’s Andy Beshear), Pete Buttigieg, Cory Booker, maybe another senator or two. Throughout July, they have an intensive schedule of debates. Six or seven. Over the course of those debates, some will rise, some will fade. In early August, in time for Ohio, let the rank-and-file decide via electronic vote. Make all the contenders commit to supporting the process and standing 100 percent behind the winner.

Weirdly enough, that could actually end up working out pretty well. A new nominee would be fresh, providing a new story and a new start. He or she would trip up Trump. This nominee could arguably then roll into the Chicago convention generating a lot more enthusiasm than Biden will. (That’s another thing—think about the anxiety that will precede his convention speech!)

Then the nominee leaves Chicago with his or her well-chosen running mate, and they spend 10 days barnstorming the swing states so that by the end of the summer, the nominee will have galvanized the party. Then that nominee would have the fall to persuade swing voters, who don’t pay attention until October anyway.

Such a process might reinvigorate a party base that today is feeling pretty dispirited and disgusted and terrified. The conversations that happen this weekend in the high precincts of the Democratic Party will help determine the party’s—and the country’s—fate. It’s risky. Lots of unknown unknowns. But it’s worth remembering that with risk comes reward.