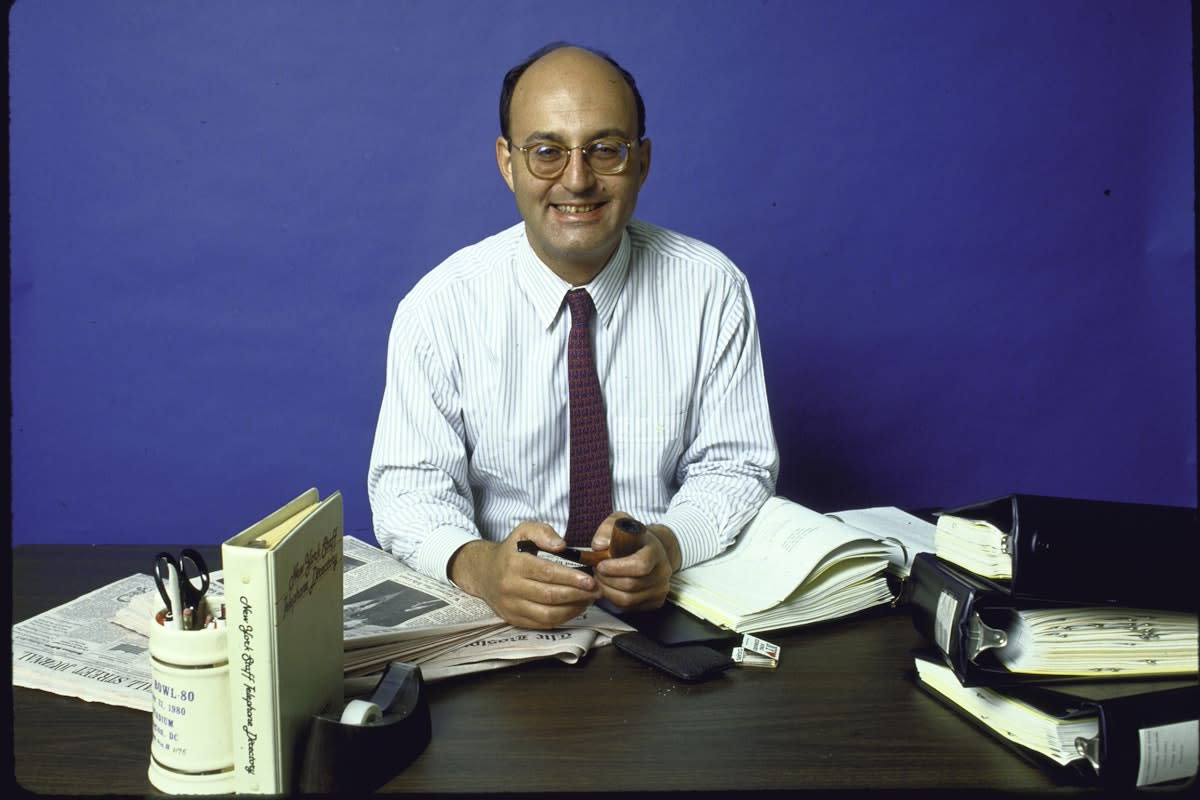

The Irrepressible Walter Shapiro

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

It was October 27, 1994, and a day earlier, Israel and Jordan had signed a peace treaty in the desert expanse that straddled the once-warring nations. It was just a year after the Oslo Accords. Bill Clinton and his press corps were on the road to Damascus, where he would be the first president to meet strongman Hafez Al Assad in Syria in almost 20 years. When our charter flight touched down at Damascus International Airport, amid propaganda posters of Assad and plenty of menacing Syrian security forces, my friend Walter Shapiro asked me to snap a few photos. One Jewish kid from the New York suburbs to the other, we looked at each other with the same can-you-believe-this grin.

What I can’t really believe is that Walter is gone, having died on Sunday morning after less than two weeks in a Manhattan hospital where he battled Covid-19, pneumonia, a brain bleed, and other ailments that came as a surprise to those who loved him.

Walter was my friend for over 30 years, a surrogate parent, and a comrade to my son, Benjamin. He was an alumnus of the Washington Monthly, the little magazine where we both served under the legendary editor Charlie Peters (see James Fallows’s tribute here). We were colleagues and competitors who worked at the then–big weekly news magazines Newsweek and Time, as well as The New Republic, but never simultaneously. Walter and his wife, the writer Meryl Gordon, took an apartment in Washington in the same Art Deco building where I lived in the 1990s—an echo of their glorious rent-controlled apartment on the Upper West Side. We’d see each other on Martha’s Vineyard, where Walter shucked corn and uncorked wines he’d driven up from the city, and skipped the popular beaches to swim in Lambert’s Cove’s quieter but bracing waters—the only time I saw him without his big trademark glasses.

Walter also enlisted me in his hobby, stand-up comedy. The venerable journalist who’d made so many people laugh in print and, later, in pixels, bravely took the stage at clubs in New York and killed, describing Iowa campaign motels so bad “they steal my soap.” I had given a funny enough toast at Walter’s birthday one year that he invited me to join him and a few other dabblers who regularly appeared at the Gotham Comedy Club but who also included future heavyweights like Jim Gaffigan and Lewis Black.

Walter was never a designated funny columnist like the late Art Buchwald or the very much alive Alexandra Petri of The Washington Post. But Walter always injected humor into the serious and found the serious truth in humor. This was a dexterous feat that not many journalists or comedians even attempt, let alone do well, but for Walter, it came naturally and earned him a big following.

In his last piece for The New Republic, published the week before President Biden withdrew from the presidential race, Walter lampooned President Joe Biden’s in-denial supporters: “A bad cold and a bit of jet lag at the debate would never be enough to upend a great president like the 81-year-old Biden at the top of his game. After all, the legendary George Abbott was directing shows in New York until he was 102; the self-taught Grandma Moses was still painting on her 100th birthday. Why should anyone expect Biden to step aside when he is still so young and vigorous?”

His two books are equally droll. His wonderful Hustling Hitler: The Jewish Vaudevillian Who Fooled the Fuhrer is the thrilling, madcap story of his great uncle Freeman Bernstein, an impresario and con artist who fleeced the Nazis by selling them 200 tons of what the Germans thought was Canadian nickel, an essential wartime metal. When Uncle Freeman’s cargo showed up in Hamburg, the much-needed material for lining guns and cannons was, in fact, a pile of junk from Canada: dented auto bodies, rusted railroad track, and such. “The Germans got a little miffed,” Walter said with characteristic understatement. Like most of Walter’s writing, amid the exquisitely timed punch line, there was a deeper truth in Hustling Hitler about family lore and a Casablanca-like call to end one’s neutrality about the battles of the day, as Humphrey Bogart’s Rick eventually did in the classic film.

Walter’s other book, One-Car Caravan: On the Road With the 2004 Democrats Before America Tunes In, an account of the pre-Iowa presidential race, captured the absurdities as well as the romance and importance of politicians trying to prove they have What It Takes. “My logic for such early-bird journalism was that the candidates would be the same people two years before the election that they would be in the fall of 2004,” Walter wrote in the Columbia Journalism Review. “The difference was that by getting out there in 2002, I could spend an entire day with John Kerry or Howard Dean without another reporter in sight. Of course, this arduous advance work did not prevent me from fatally misjudging John Edwards, but that was another type of problem.” Walter had run for Congress as a young man and always had a former candidate’s empathy for those in the arena.

Walter’s journalism was very good and held up over time, and when he was wrong, he acknowledged it. His opinions were always backed by reporting and encyclopedic knowledge. Like Flaubert, he understood le mot juste and had an eye for the perfect anecdote. Walter unearthed one of the most revealing tidbits of the 1988 presidential election: The Democratic front-runner, Massachusetts Governor Michael Dukakis, had spent a beach vacation reading a book on Swedish land-use planning. He knew that if you were standing around with a huge pack of reporters, that meant you weren’t doing it right. I remember how he befriended sources over long dinners or fantasy baseball sessions, including one extremely high-ranking national security official.

Being cutting without being snarky or cynical, patriotic without being trite and treacly, is not easy. Walter understood the difference, and that is one reason he built a big audience during a peripatetic career that took him to the publications mentioned above, as well as The Washington Post, Salon, USA Today, Esquire, Yahoo News, Roll Call, Yale University, the Kennedy School, and the Brennan Center. Walter was a brand in the best sense.

He was also endlessly kind, from the first time he held my son after his bris to a couple of weeks ago when Walter and Meryl dined with my now 25-year-old and his fiancée at their home. He was endlessly fun, buying cowboy Stetsons and toy MTA subway cars for him as an infant and dispensing wine and advice when he was older. Walter and Meryl, married for nearly 44 years, were the best company. They were who you wanted to be seated near at a dinner party or, better yet, have all to yourself. They always ate well. Walter told me how he kept a list of the regional runners-ups in the James Beard Awards, the Oscars of the food industry. I laughed when he started telling me about some restaurant in Topeka.

On Sunday, as I shared news with folk of Walter’s sudden hospitalization and turn for the worse, I was struck by how many people wrote me that Walter had mentored them; journalists whom I didn’t know Walter knew. Within hours of his passing on Sunday, social media was ablaze with tributes to Walter.

When a man dies at 77, it’s usually seen as sad but not tragic. Walter’s passing was not only surprising and mournful but tragic because he had not slowed down. He still had, and this is not a word you use with septuagenarians, so much potential. He still had at least four jobs by my count: Roll Call, Yale’s Political Science Department, the Brennan Center, and The New Republic. He was working on a Broadway adaptation of Hustling Hitler, a potential The Producers for our times, and God knows what else. He had another Democratic convention and Vineyard summer on his agenda. He still had so much more to do. He’s gone, and I still can’t believe it.