Old nuclear missile silo plagues Placer County minds. What lurks outside their homes?

Stan Everhart looked out from his backyard in Sun City Lincoln Hills and saw an open field — green and lush in the rainy seasons and more like dry kindling in the summer, peppered with a few trees along the horizon and the occasional rabbit sprinting through. At one point in the distance, the landscape slopes upwards, blocking his view of a mostly abandoned road and what lies beyond.

Recently, his view has changed. Now, along the perimeter of his neighbor’s fences thick yellow poles jut out from the ground, each surrounded by three more poles that act as a barrier. Perhaps a bit unsightly, Everhart knows that they are an important part of a cleanup effort he and his neighbors have been petitioning for over the last two years.

“When we bought the house, it was like ‘quick, hurry up, buy it fast,’” Everhart said. “So we bought it and then about six months later, we started hearing about contaminated soils out back.”

Everhart had no idea about what was hiding behind the field when he moved into his Sun City home, a common experience of those living in his neighborhood.

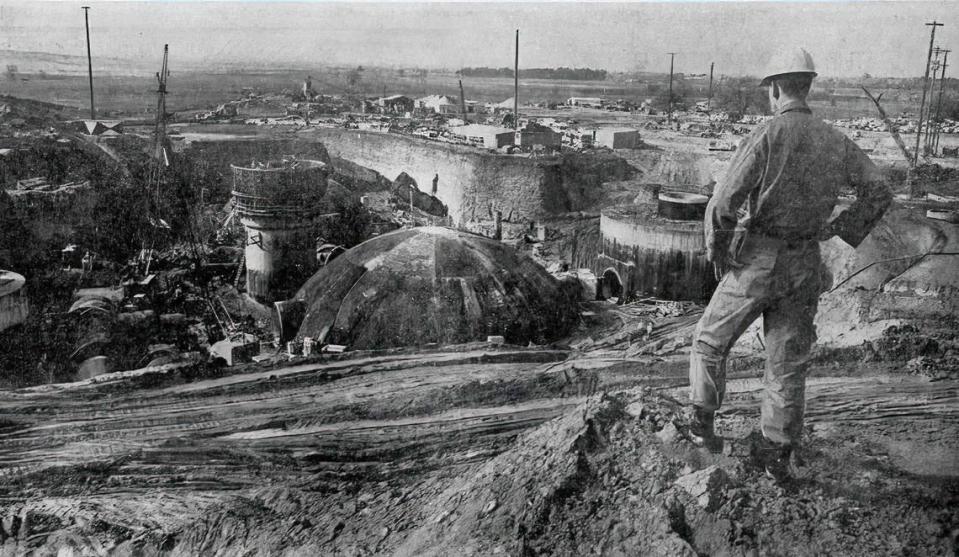

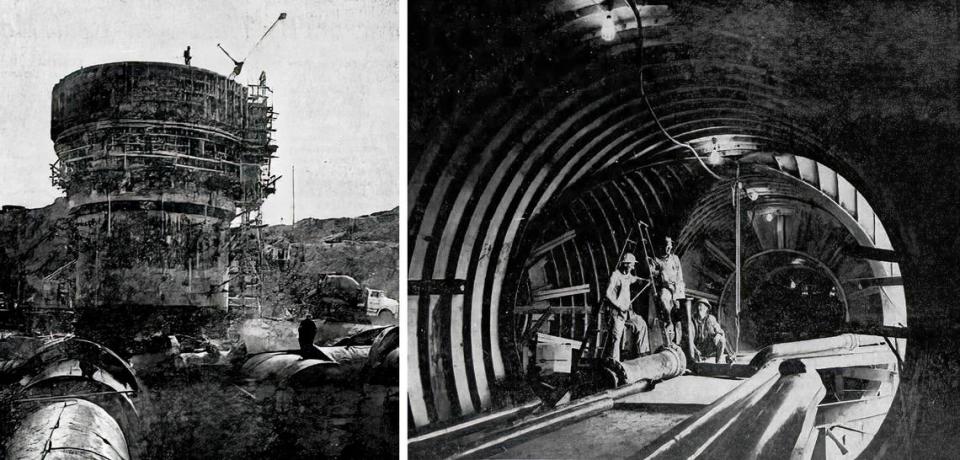

Just past the upward slope that hides the road, small piles of concrete sit behind a metal fence. Also difficult to see from the road, they are the only visible signs of a once fully operational nuclear Titan-1 missile silo site that the U.S. government built in 1962 for $44 million, or roughly $440 million in today’s dollars.

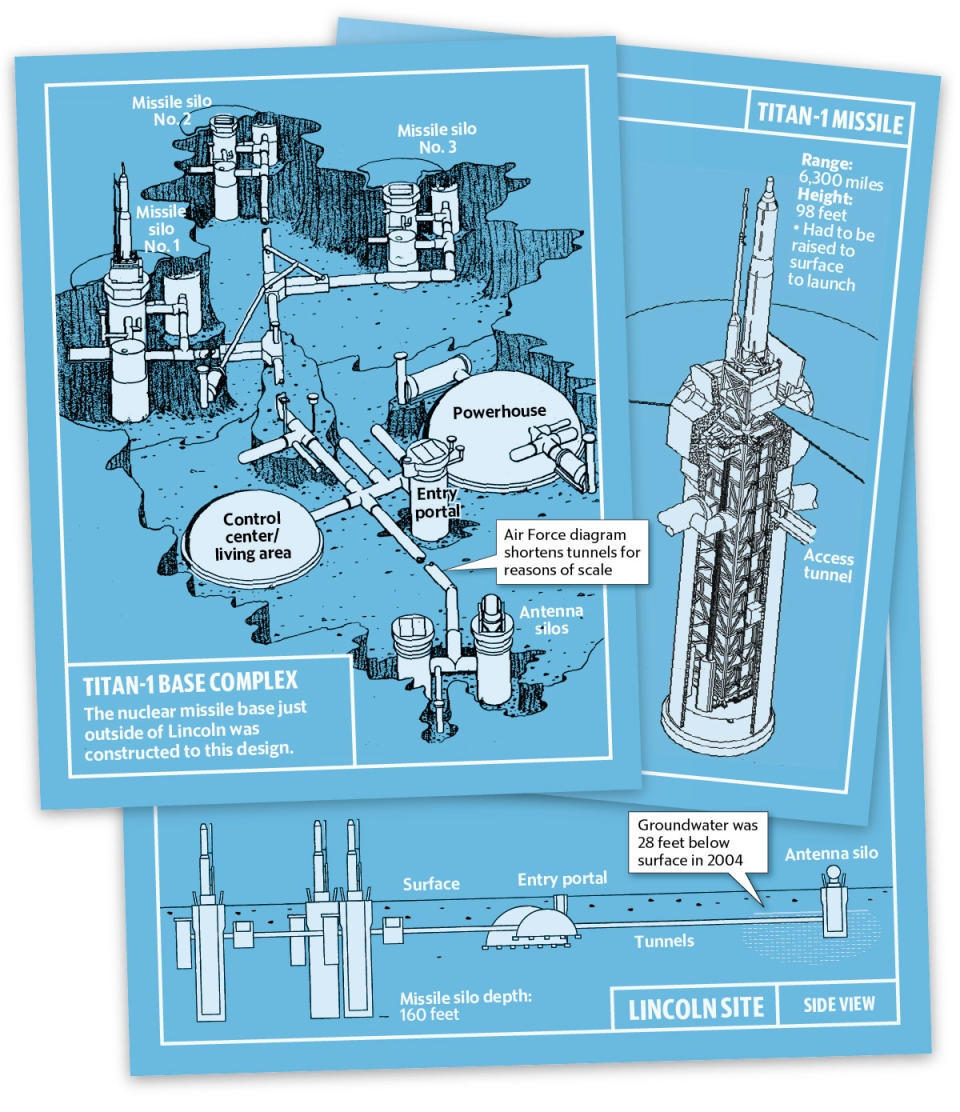

Titan-1 missiles were a Cold War-era project, the nation’s first intercontinental ballistic missiles. The Lincoln site, one of three in California, took up dozens of acres in a remote part of Lincoln, near what’s now the intersection of Sierra College Boulevard and Highway 193 — with miles of tunnels, three silos that were 160 feet deep and other operation and housing rooms all buried underground.

The silos leaked a chemical, trichloroethylene, or TCE, after it was used to clean the site during its three years of operation, and groundwater and soil vapors holding the toxic contaminant have spread, nearing Sun City homes. The yellow poles, or more accurately monitoring probes, see how far the plumes have reached and how concentrated with TCE they are.

A Placer County grand jury report released last month found that nothing substantial was ever done to clean TCE from the site, which was first discovered in 1991 to have leaked into the surrounding area.

Despite the now-dated discovery of TCE, in 2022 a group of residents became aware of the hazardous materials that were spreading in through the site, in part thanks to retiree Anne Constantin Birge, a resident who worried about what was left at the site after seeing lead bullet shells while walking there with her husband. The bullet debris turned out to be from a former shooting range – but her research into the site led her to learn about the TCE contamination.

Map: Sacramento Bee | Source: U.S. Army Corps of Engineers

“It has never been cleaned up. It’s been getting bigger and bigger, it’s been moving,” Birge said.

Birge learned that TCE was used to clean oxygen lines, which was important due to the highly reactive nature of the missiles. Despite being an ingredient in some household cleaning products, TCE has long been known to be harmful to people who ingest or are exposed to it for long periods of time.

As she began finding out more, Birge collected documents, newspaper clippings and maps that now fill a dozen four-inch binders. She also assembled a citizen remediation committee with Everhart, other concerned neighbors and Lenny Siegel, the executive director for the Center for Public Environmental Oversight.

What does the grand jury report mean for the site?

In the early 2000s, cleanup efforts were piloted by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, using extraction trenches and wells that removed 10 pounds of TCE from groundwater.

Efforts were paused in 2009 when the Army Corps began questioning if the county should be in charge of cleanup because of their ownership and uses of the site, The Sacramento Bee reported in 2011. The questioning prompted a back-and-forth with the county.

Though this put cleanup on hold, it was a fair question for the Army Corps to ask, Siegel said, because the county had built on the site after the missile silos were decommissioned and used it as a shooting range. But the Army Corps ultimately took responsibility for the TCE leak and reinitiated a remedial effort investigation in 2018.

“Everything stopped for a decade. The official reason is that they couldn’t agree who was responsible for doing the cleanup,” Siegel said. “But the technical term is called asleep at the switch. Somebody just let the whole thing slide as the contamination, the plume of TCE, moved toward the residential neighborhood and contaminated land.”

From 2000 to 2022, the plume moved southwest toward Sun City at an average rate of 87 inches per year, the grand jury found, and has moved a total of 1,800 inches, or 150 feet.

The grand jury concluded that clean-up and public awareness need to be a priority, though Siegel said they are limited as it is not in their jurisdiction to make recommendations to federal and state agencies, the Army Corps and California Water Board, respectively.

Instead, the report will act as a “squeaky wheel” for the Army Corps, Siegel said, which has more formerly used defense sites, or FUDS, to clean than it has funding for.

“The fact that the grand jury has weighed in means politically that the Army Corps and Water Board are going to feel more pressure to clean it,” Siegel said.

The Army Corps has been feeling that pressure as residents spread the word to an unaware community.

Last fall, the site was ranked in the top 10 priorities of the Army Corps at a national level, Carmen De Fazio, the FUDS program manager said. That designation doesn’t refer to risk, but rather is a response to the public concern and the priority the Army Corps is placing on hazardous, toxic and radiological waste sites.

Tyler Stalker, chief of public affairs for the Sacramento division of the Army Corps said they didn’t realize the public knew so little about the work being done to clean the site, which started again in 2018.

To gauge public sentiment, the Army Corps mails out a public survey every two years, and never received many responses, Stalker said. That changed significantly during last year’s survey, which prompted the Army Corps to form a Remediation Advisory Board.

“We’ve been communicating out, perhaps we could’ve done it better,” Tim Crummett, an Army Corps project manager said. “All of a sudden it became a little bit sensationalized in the community.”

Gauge scope of the contamination

To increase transparency, the grand jury made recommendations to the Lincoln City Council to include a page on their website about cleanup efforts and request that the Army Corps publish videos of meetings held by their Restoration Advisory Board.

Crummett said that the Army Corps has already improved communication since the grand jury was evaluating them, but that they will help in any way possible.

The Lincoln City Council will also have to appoint a member of the advisory board.

“Places where there’s a lot of public interest tend to get a faster response and that’s what we’re seeing. I think it’s justified because the plume is heading towards a residential area,” Siegel said.

Birge said that the support of local U.S. Rep. Kevin Kiley, R-Rocklin, and bipartisan agreement on the issue has also been important to seeing more attention and funding from the Army Corps at the site.

Lincoln City Manager Sean Scully said that the city council agrees with all of the recommendations made by the grand jury, and have been assisting with advocacy and sharing information with the public in recent years.

“Everybody sort of wants the same thing,” Scully said. “What we advocate for is timeline, to get it done in an expedited manner.”

Since 2022, residents said they have seen some progress. The Army Corps contracted the Parsons Corporation and is monitoring soil vapor and groundwater throughout 2024 with probes and monitoring wells that they have installed over the years to get a better sense of the scope of the contamination. Mainly, they are looking at TCE concentration levels, and installed new wells this year to look specifically close to the Sun City homes, the ones Everhart sees from his backyard.

Though it is too early to say how long remedial action will take, the Army Corps should have a full written report done later this year that outlines their remediation plan, Scully said.

Per the Army Corps’s presented timeline, remediation should begin in 2027, following the ongoing investigation/feasibility study phase. According to Crummett, their current total cost estimate for remediation, which can change yearly as necessary, is $26 million.

“Clean it up as fast as you can, make it go away, it helps the developer, helps the city, real estate, people trying to sell homes” Everhart said. “They know they have to do it so instead of working on it 25% of the time, why don’t you work on it 100% of the time?”

What is the risk for residents?

Siegel said that when he first met with concerned Lincoln residents, he told them not to panic. Because the surrounding area does not get its water from the TCE-contaminated groundwater, residents are not yet at risk. For them to be affected by the chemical, they would have to be exposed to vapor intrusion, which occurs when contaminated soil gas is underneath a structure and harmful vapor moves up into the building.

There is a smaller soil vapor plume being studied, but Siegel said the TCE in the large groundwater plume nearing homes in Lincoln Hills can also vaporize into the soil, which is a concern. Unlike radiation, proximity is not a concern, because there needs to be a clear pathway of exposure, like living on top of soil with contaminated gas.

Exact perimeters of the groundwater and soil vapor plumes are being studied, though estimates from last year show the groundwater plume very close to some homes.

Siegel said that because of the unique nature of the community’s older demographics there may also be less concern for the health issues caused by long-term exposure.

“You don’t have young children living in the homes so people are probably less concerned about health issues than if there were young children there,” Siegel said.

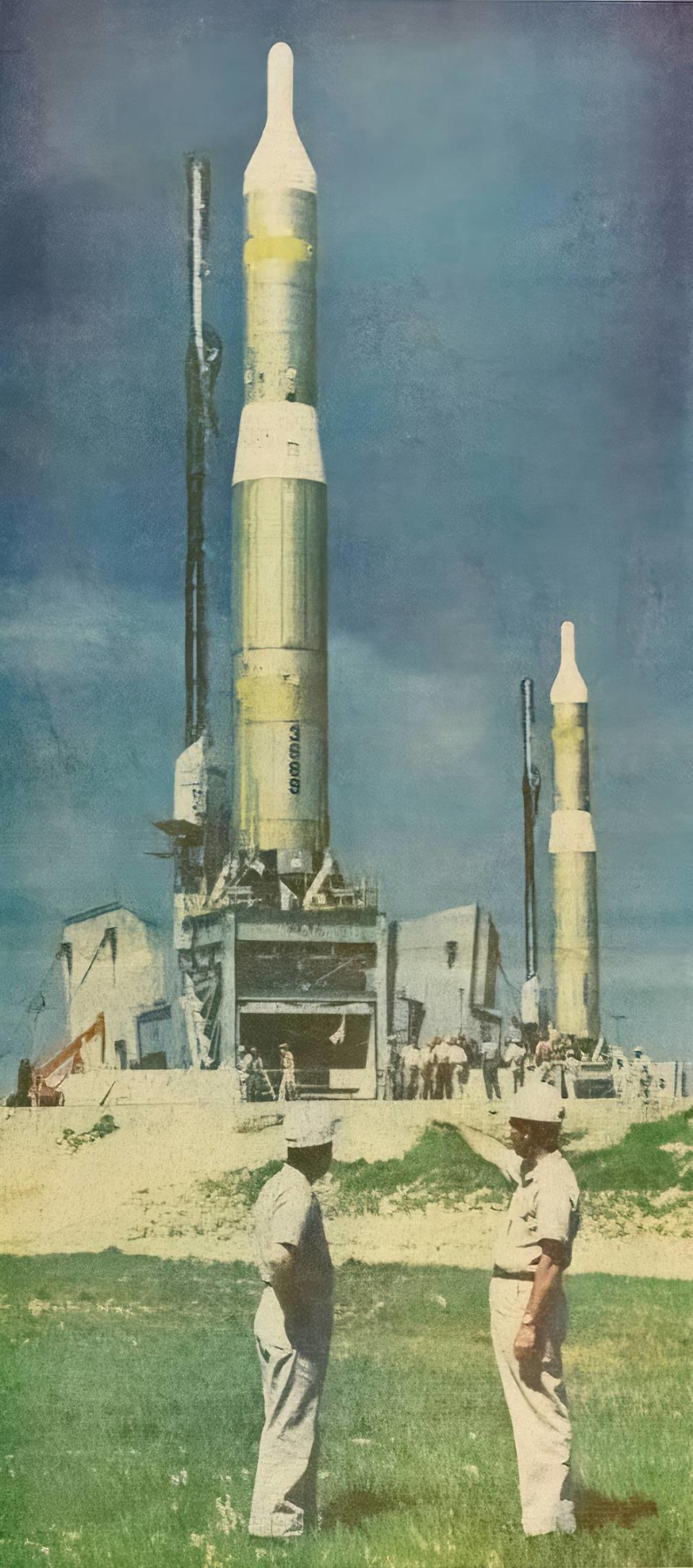

Graphic: Nathaniel Levine | Source: U.S. Air Force

Risks are also especially high for pregnant women because TCE can cause birth defects.

California’s Environmental Protection Agency set the maximum contaminant level in groundwater at 5 micrograms per liter. At the highest point of measurement so far, TCE was recorded at 530 micrograms per liter at the Titan-1 site, according to a water board report.

With long term exposure to TCE, the risk of cancer, psychological effects, liver and kidney damage can increase, the grand jury said.

Advocates worry that Sun City Lincoln Hills may not be the site’s only neighbor for long. One planned development, Hidden Hills, is currently starting underground infrastructure, Scully said, but is taking Army Corps advice on how to proceed cautiously.

“This area of Lincoln is planned for fairly significant residential growth,” Scully said. “It’s really important to us that we’re considering and approving projects that are going to be safe for people to live in.”

Another area planned for development, called Crocker Knoll, sits right on top of the groundwater plume, between the old missile silos and Sun City. Its owner has no plans to build houses on the land until he can guarantee it has been cleaned, but hopes that will be soon.

Though the grand jury also concluded that no nearby residents are exposed to immediate hazards right now, they stressed the urgency of remediation.

“It is essential for proper authorities to prioritize and initiate cleanup efforts to address these potentially serious hazards.”

Siegel might have told them not to panic, but the residents who began advocacy efforts two years ago are definitely not relaxed.

Everhart communicates with the Army Corps and water board often, asking about new information that has come up in his research and how Hidden Hills construction will be monitored.

Birge still fears for the area, reading Army Corps documents and worrying about environmental impact, how long cleanup will take and what other problems the silos may be causing while they lie dormant.

“We’ve been lied to a lot. We’ve been ignored. We’ve been treated like we don’t know what we’re talking about, and yet we’ve had the time to research all of this using their own documents,” Birge said.