One of the most dangerous roads in Sacramento saw third death this year: A dad on a bike

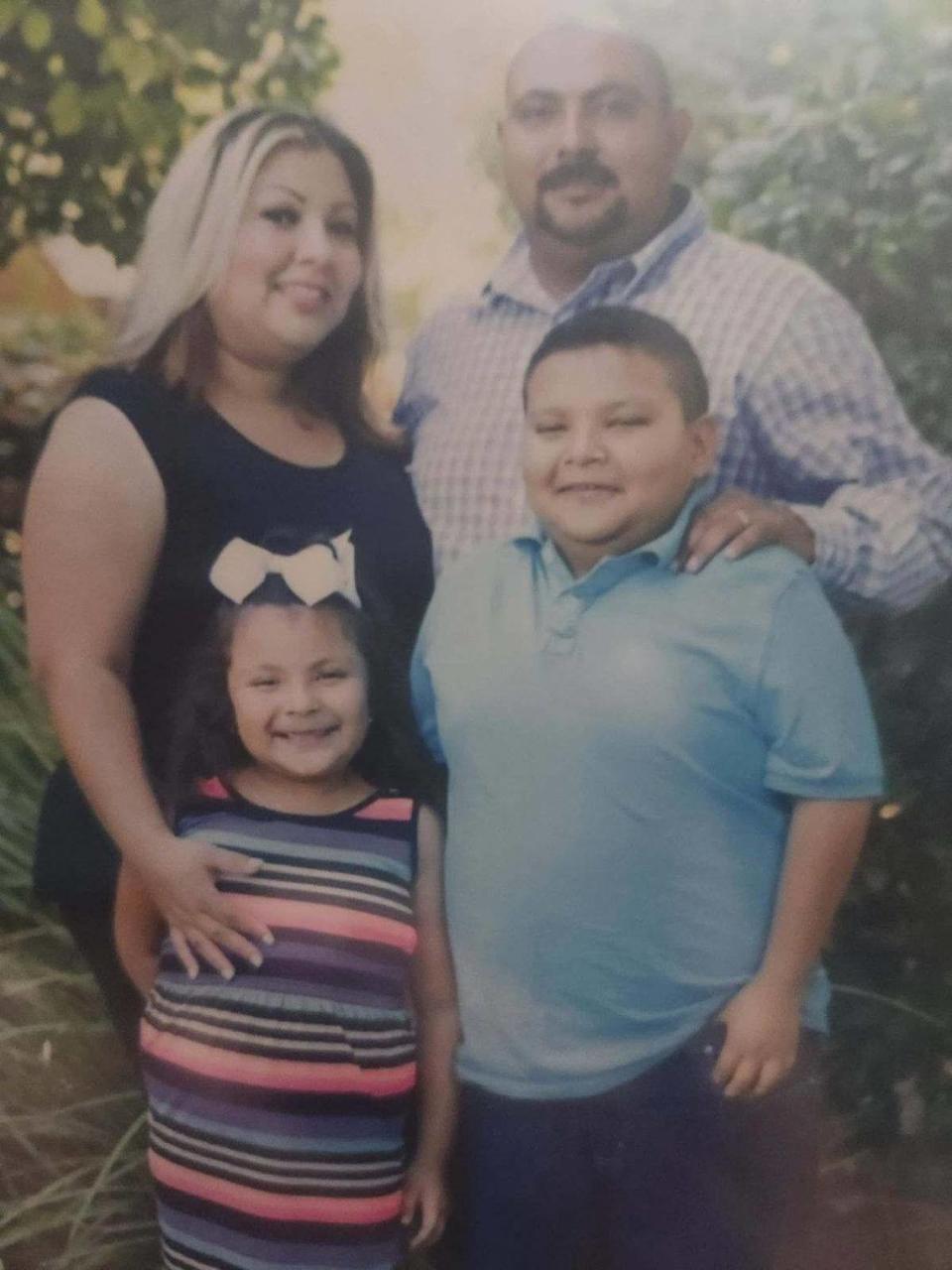

Jose Valladolid Ramirez, who married his childhood sweetheart and was teaching their two kids how to fix cars, was fatally struck by a Dodge Ram on June 10 while riding a bike on one of the deadliest streets in Sacramento. He was 36.

Valladolid was the third person to die this year on Fruitridge Road, where the city allows drivers to travel at lethal speeds. James C. Lind and David Rink, both pedestrians, were hit in areas where the posted limit is 40 mph. Valladolid died west of 88th Street, struck while biking through an industrial area where the speed limit is 50 mph.

A study published in the public health journal Accident Analysis & Prevention found that when a car strikes a pedestrian at 24.1 mph, the average risk that the pedestrian will die is 10%; at 40.6 mph, the risk is 50%; and by 48 mph, the risk of death is 75%.

Such deaths are almost always preventable through changes to infrastructure, as other countries with far lower fatality rates and some U.S. cities have demonstrated. Following this evidence, Sacramento leaders made a “Vision Zero” promise in 2017 to eliminate all traffic fatalities by 2027.

Although the city has followed through with some safety enhancements, it remains far from that goal.

UC Berkeley’s Transportation Injury Mapping System shows that from 2018 through 2023, 167 pedestrians and cyclists were fatally struck in the city, and in 2024 to date, The Sacramento Bee has reported on 12 pedestrians and cyclists who have died: Mattie Nicholson, 56, Kate Johnston, 55, Jeffrey Blain, 59, Aaron Ward, 40, Sam Dent, 41, Terry Lane, 55, David Rink, 51, Tyler Vandehei, 32, James C. Lind, 54, Valladolid, Larry Winters, 76, and Sau Voong, 84.

On Fruitridge alone, the Transportation Injury Mapping System shows 12 fatal crashes from 2020 through 2023.

In line with its Vision Zero promise to stop these deaths, the city has plans to make safety improvements to the street. As with many road safety projects in the city, officials have been slow to implement them.

Sacramento has secured funding to make some improvements to a 1.8-mile stretch of Fruitridge between Stockton Boulevard and Power Inn Road, which would include the 65th Street Expressway — the intersection where Rink was hit and killed. It would likely include lane reductions, which help slow down traffic by reclaiming space from motor vehicles. That project is under environmental review and is far from construction.

The city also just won a $381,000 Caltrans grant to plan changes to the western part of Fruitridge, from South Land Park to Stockton Boulevard. That project is in the earliest stages.

A spokeswoman for the city, Gabby Miller, said that in the meantime, the city had asked police to step up enforcement. Other than that, “There are currently no plans for short-term emergency safety measures along Fruitridge.”

The city also has several unfunded ideas for Fruitridge. A separated bike path — which in Sacramento often means a path with plastic barriers between cyclists and cars — is listed in the city’s Transportation Priorities Plan for Fruitridge between Florin Perkins Road and South Watt Avenue, running through the site of the crash that killed Valladolid.

That plan is designated as a “lower” priority.

Lane reductions — which would help slow down traffic by decreasing the space for moving cars — are marked as a “higher” priority for parts of Fruitridge that include the intersections where drivers killed Rink and Valladolid.

None of these ideas have been implemented.

“I just want that road to get fixed,” said Valladolid’s wife, Mayra Miranda. She said she doesn’t want another family to go through the same experience.

“There’s already three deaths since the year started,” she said. “Why don’t you — the city — look at all that?”

The Sacramento Bee is chronicling all traffic-related deaths on city streets in 2024 not only to show the causes of these fatalities and what can be done to prevent them, but also to memorialize the people we lost.

After a cyclist’s death, the widow foots the bill

After the crash that killed Valladolid, the Sacramento Police Department immediately arrested the driver. The 57-year-old man was booked on charges related to driving under the influence and possession of a controlled substance. He was in a 2011 Dodge Ram, whose hood height — over 40 inches — makes it 45% more likely to kill a pedestrian than smaller cars, according to the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety.

Though police placed blame on the driver, Miranda has had to bear the full cost, both emotionally and financially. On top of the grief of losing her husband, a receipt shows that she’s paid $1,000 to the funeral home, with a remaining balance of $1,490. A GoFundMe gained no traction. Until she pays in full, the funeral home won’t release her husband’s ashes.

She wants to inter his remains in a columbarium. A purchase agreement shows it’ll cost $6,300.

Since his death, she’s had to take more than a month off, too depressed to perform her job as a medical transporter. At first, she felt numb. She said she has to go back to work soon, even though, “Now, I feel it more. His absence.”

He had been in her life for more than 20 years.

“Basically,” she said, “we grew up together.”

A Sacramento story of young love

Jose Valladolid Ramirez was born Nov. 30, 1987, in Mexicali, Mexico, to Ofelia Ramirez and Armando Valladolid. His mother brought him to the U.S. as a small child, and he was raised in the Sacramento area.

He was shy when he was young, Miranda said. She first saw him at her cousin’s quinceañera, when they were both still kids. He was 15 and, she remembers, standing alone in a corner at the party. She was 16, and she thought there was something sweet about him.

She didn’t approach him that night. But the next day, she asked the quinceañera girl for his number, and she called him. Valladolid didn’t remember seeing her at the party, and he sent a friend to scope her out while she worked as a cashier at the Jimboy’s Tacos on Stockton Boulevard.

Miranda said the friend relayed a message to him: “You should come and look at her.”

Valladolid, reassured that the girl from the phone call was cute, came to the fast food restaurant during her break to meet Miranda.

“I was the one always doing more of the conversation, the talking, because he was more shy,” she remembered. “He said he never had a girlfriend before that.”

Shortly after they met, on Valentine’s Day in 2003, he sent one of her friends into the Jimboy’s with a stuffed bear. The friend handed her the bear and told her that Valladolid wanted to go on a date, and he was waiting outside.

They almost instantly became inseparable. She moved in with him and his mother the next month, she said, against the wishes of her own parents. They were in love, and she was determined.

“Basically,” she said, “we grew up together.”

A growing family and a terrible loss

A few months into their relationship, Miranda became pregnant. She was adamant about staying in school, even though the pregnancy was hard, and Valladolid supported her. In her third trimester, “I was just so big and tired,” she said. “It was so cute though — he used to stay up and do my homework.”

At the very end of her full-term pregnancy, the young couple received devastating news: The doctor couldn’t find the baby’s heartbeat. Mariana was stillborn on Feb. 11, 2004. Their hearts broke.

About two or three months later, Miranda found out she was pregnant again.

She was 17 and terrified to lose another baby. But Valladolid and her mother comforted her, and she decided to see the pregnancy through.

Her boyfriend was sweet to her: It had been their custom, as broke teenagers, to go to McDonald’s to split a McChicken. During her pregnancy, she remembers him insisting that she eat the whole sandwich. She couldn’t do it. It didn’t feel right, not sharing with him.

Valladolid had dropped out of high school, but with his help, Miranda graduated in the spring of 2004. She was pregnant with their second child.

Their son, Giovanny Valladolid, was born Jan. 17, 2005.

The couple had moved into a one-bedroom apartment, where they pushed their bed into a corner and placed the crib across from the window. They were so young that they would sometimes make ridiculous parenting choices, Miranda recalled. One day, when Giovanny was about two months old, he started wheezing. Instead of taking the baby straight to the hospital, the scared teens took Giovanny to her mother’s house, where they were chastised and told to take the baby straight to the hospital. He was diagnosed with asthma.

The young parents learned to administer breathing treatments. Like everything in those days, they muddled through it together. Valladolid got a job making stucco to support his partner and their baby. He came home from work every day covered in dust. A few years later, when they decided to have a second baby, they lived with his mother so Miranda would have more people to care for her during a high-risk pregnancy that doctors said was high-risk.

On Jan. 23, 2010, Miranda gave birth to their third child, Amayrani. The next year, Valladolid and Miranda married.

They left the children with their grandmother and snuck off to Reno with one of Valladolid’s friends on May 21, 2011. In a small, simple ceremony at the Silver Bells Chapel under an arch laden with flowers, they said their vows. After the service, they rode in a white limousine to a casino, where they had a celebratory meal at a buffet before they drove home to their children.

Within a few months, he got a better-paying job at a landscaping company. The family moved into a nicer home. Miranda encouraged Valladolid to drive with her to the city of his birth, where he visited his father — a man he had not seen since he left Mexico as a young child. Vallladolid, who was then in his mid-20s, was elated. The couple started traveling south to his family every few months, making up for lost time.

On Valladolid’s birthday in November, he had a big party in Mexicali. Everyone danced and drank and laughed for days. They rented a bounce house for the kids. They ate slices of tres leches, his favorite cake.

After Miranda helped Valladolid reunite with his father, she remembers him telling her, “Thank you for making my dream come true.”

A mother deals with a father’s death

A few years ago, Miranda and Valladolid started fighting more, and they eventually separated. He moved in with his mother.

Despite their separation, Valladolid still came to see her and their children frequently, she said — often every day. He taught Giovanny how to change the oil in his car. Giovanny works and goes to classes, so Valladolid spent more time with his youngest, Amayrani. Together, he and the girl had replaced the transmission on a neighbor’s car.

Valladolid died just a few days before his daughter’s eighth-grade graduation.

Around 4 in the morning June 11, Miranda heard a knock on the door. It was an officer from the Sacramento County Coroner’s Office. Her husband was dead.

The Coroner’s Office said Valladolid was on a bicycle that night, not in his Charger. Miranda wasn’t sure why. He didn’t really ride a bicycle, as far as she knew. But they had grown apart, and she didn’t understand what he was doing with a lot of his time.

She did understand a few things about the crash, though.

She saw that Fruitridge Road doesn’t have a bike lane where he was riding, near 88th Street. She saw that it was extremely dark at night. The speed limit there is 50 mph. It’s dangerous, Miranda thought. She knew her children’s father was the third person to die on the road this year.

She also knew her son needed to replace the brake pads on his car, and usually, that was something his dad would help with. She found Giovanny in the shed one day, holding a bag of his father’s tools and crying.

Jose Valladolid Ramirez

Auto mechanic, husband, father and South Sacramento resident

Age: 36

Died: June 10, 2024. He was struck by a car on Fruitridge Road near 88th Street while riding his bike.

Survived by: Wife Mayra Miranda and two children, Giovanny and Amayrani Valladolid; brothers Jorge Ramirez and Carlos Valladolid; and parents Ofelia Ramirez and Armando Valladolid.