Powerful Florida family sold DeSantis administration toxic land, lawsuit alleges

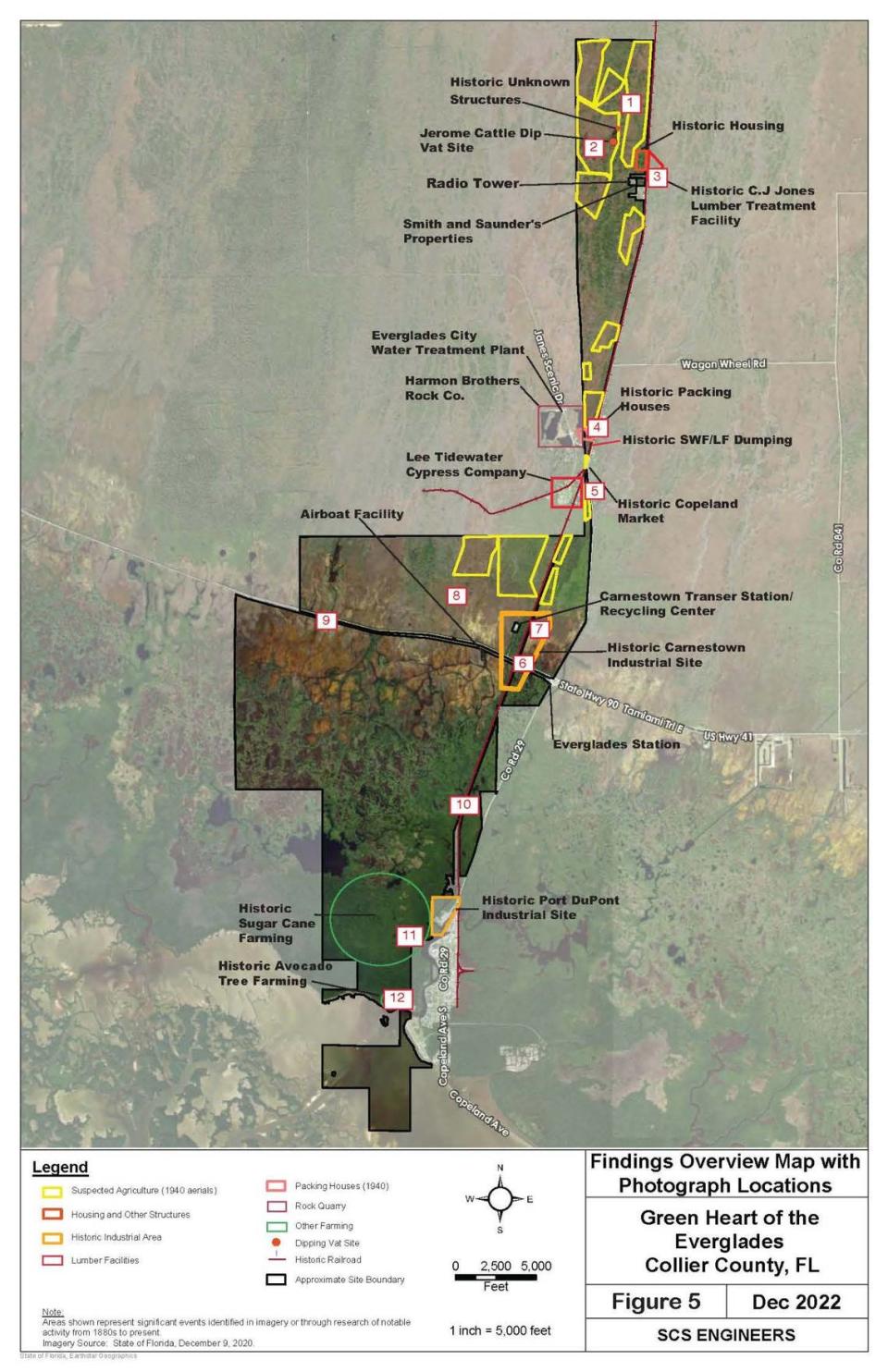

Last year, the state of Florida purchased more than 11,000 acres for nearly $30 million from the powerful Collier family near Everglades City for conservation. Now, a former employee of Parker J. Collier — the matriarch of the family from which Collier County gets its name — claims most of that land is toxic.

In a federal lawsuit unsealed late last week, Sonja Eddings Brown — Collier’s former employee — says independent tests show that at least 8,000 acres of the land sold are likely contaminated with a wood treatment chemical called creosote related to a 1956 fire she claims the family never cleaned up.

Long-term exposure to creosote may cause birth defects and cancer, according to the federal Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. Brown contends that Collier never disclosed contamination to the state.

“This case centers on a businesswoman and matriarch of a powerful Florida family, Parker Collier, and the unlawful acts she perpetrated to enrich herself by engineering the promotion and sale of 8,000 acres of land contaminated with deadly creosote in the Everglades,” states Brown’s unsealed complaint.

Collier wholly denied the allegations through a spokesperson to the Herald/Times.

“This claim is without merit and completely baseless,” wrote the spokesperson by email. “We categorically refute all allegations made against us and will vigorously defend our position and reputation, utilizing the full extent of legal remedies available to us.”

The lawsuit is part of a larger employment dispute with Parker Collier. The lawsuit alleges that Parker Collier misrepresented the contamination of the Green Heart of the Everglades land to Brown while she was pitching it to the DeSantis and Trump administrations in 2020. Brown claims Parker Collier then fired her once she started asking questions about the contamination while also raising concerns about corruption in a separate development deal in Collier County.

It’s unclear if Brown’s allegations about the contamination of the Collier land – sold to the state in a project dubbed the Green Heart of the Everglades – will jeopardize conservation efforts. The purchase represents the final piece of significant private land separating the Everglades ecosystem. It sits between the Fakahatchee Strand Preserve State Park and the Big Cypress National Preserve. It is home to 39 threatened or endangered species such as the American Crocodile, Black Bear and Florida Panther, according to a project summary.

RELATED CONTENT: As they wait and work for Everglades restoration, the swamp keeps dying

A spokesperson for the South Florida Water Management District, which purchased the land on behalf of the state, told the Herald/Times in an email that a “comprehensive environmental assessment” of the land was done before the transaction, as is standard practice. The Florida Department of Environmental Protection and the governor’s office declined to further address specific questions, with the governor’s staff directing the newspaper to the District for information.

Ernie Cox, a lobbyist for the environmental nonprofit WildLandscapes International who orchestrated the state’s purchase of the land, disputed that it was toxic, saying the District’s environmental assessment addressed the creosote contamination on land that wasn’t part of the parcel sold to the state.

“The people that do [these assessments] know their stuff and they would have reviewed all the backup, and it looks like the conclusion was this was cleaned up many years ago and doesn’t present a problem,” Cox said.

He added: “If there was a problem, WildLandscapes would have raised it.”

Cox said he never worked with Brown in the land sale. The lawsuit says Brown was fired in 2020, during early promotion of the sale. By the time the land was sold to the South Florida Water Management District, she was no longer involved.

The Herald/Times reviewed the environmental assessment. It refers to a past creosote contamination in the unincorporated area of Jerome about 150 feet east of the parcel sold to the state, but notes it has since been remediated, citing government reports. No physical sampling was done for the report.

Brown claims she conducted her own environmental testing reviewed by a toxicologist on adjacent land to the parcel sold in Jerome in May and June. Those tests show the land is toxic, indicating a large portion of the Green Heart of the Everglades land is likely also toxic, she claims.

“Recent testing of land immediately adjacent to the Everglades Parcel indicates that creosote-related contaminants remain on the land and in the drinking water to this day,” states Brown’s complaint.

READ MORE: It’s the $4 billion ‘crown jewel’ of Everglades restoration. But will it be enough?

A BRIEF HISTORY OF TOXIC LAND

Jerome is a small, rural area of Collier County at the edge of the Everglades, north of Everglades City and Copeland. It was built around 1920 and housed employees of the C.J. Jones Lumber Company, the “biggest manufacturer of treated wood products in the Southeast United States,” per Brown’s complaint.

C.J. Jones leased that land from a company owned by the Collier family, according to the lawsuit.

A 1956 fire led to 3,000 gallons of creosote exploding while the company was shutting down operations, according to the lawsuit and the District environmental assessment.

For decades afterward Jerome residents complained about their water quality, per the complaint.

In 1990, the then-Florida Department of Environmental Regulation ordered the Collier business to remediate the land and provide alternative drinking water to the town, according to a consent decree between a Collier family business and the state.

But in 2003, dozens of Jerome residents still believed their water was tainted by creosote, according to reporting at the time by the Naples Daily News, and sued the Collier family business.

The Collier businesses settled, according to Brown’s complaint.

Brown’s physical samples of the land adjacent to the parcel sold to the state were reviewed by Dr. James Dahlgren, a toxicology expert who came to fame helping Erin Brockovich uncover an energy company’s role in contaminating California water in 1993. The samples show Jerome’s soil and drinking water are still contaminated, and therefore the surrounding areas are likely still contaminated, including a large portion of the land sold to the state.

Dahlgren concluded the “‘water and soil around Jerome and Everglades City are contaminated and need to be remediated or it will be a toxic source for hundreds of years,’” states Brown’s complaint.

Those results are “‘the tip of the iceberg reflecting likely widespread water contamination’ that poses significant health risks,” Dahlgren said, according to the complaint.

The Herald/Times requested to interview Dahlgren but he wasn’t available by time of publication.

In addition to largely completing public ownership of the Everglades ecosystem, the Green Heart of the Everglades land won’t be mined for minerals or drilled for oil, because the Collier family businesses also sold those rights to the state, per the sales agreement.

The Green Heart of the Everglades land is “one of the only subtropical regions in North America” and “is known to support up to 44 native orchids and 14 native bromeliad species, including one of the world’s rarest plants — the ghost orchid,” per the project summary. The ghost orchid was featured in the 2002 film, Adaptation, based on journalist Susan Orlean’s 1998 non-fiction book, The Orchid Thief.

“The location of this assemblage of lands is unique and irreplaceable,” states a South Florida Water Management District May 11 memorandum on the project. “The ecological values of these lands are extraordinary, along with the ecosystem services provided by these lands.”

The memo continued: “This acquisition has broad-based public support, and is an incredible opportunity to improve water quality, enhance habitat connectivity, coordinate management with adjacent conservation lands, and protect these lands forever.”

Cox, the WildLandscapes lobbyist who coordinated the sale, said he worried Brown’s allegations would stir up unnecessary controversy about a purchase he viewed as above board.

“My fear is that someone is trying to say this transaction wasn’t done properly,” Cox said. “She’s saying the [creosote contamination] was hidden. And it wasn’t.”

Herald staff writer Gabriela Henriquez Stoikow contributed to this report.