‘Prosecuting’ Donald Trump: How Kamala Harris’ DA background shapes her campaign style

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

The presidential election features a tough prosecutor versus an unrepentant felon.

Vice President Kamala Harris, a former district attorney and attorney general, will know how to dig in and raise serious, pointed, tough questions about former President Donald Trump’s 34 felony convictions.

She reminds voters of her background on the campaign trail. In her first big rally this week, she told supporters “I know Donald Trump’s type,” a reference to the people she dealt with as a prosecutor.

But while her style has been hailed in recent years by Democrats, it’s also provided strong material for conservatives to paint her as combative and antagonistic.

How Harris’ prosecutor style plays during this election campaign could go a long way to determining who wins. But can anyone make the case against Trump, whose support has been steady in the 40s in national polls, even after his conviction on charges of falsifying business records?

Here is what some experts say:

“One of Biden’s problems was an inability to consistently make the case against Trump,” said Kyle Kondik, managing editor of the nonpartisan Sabato’s Crystal Ball, which studies elections.

“So far attacking Trump on all his foibles doesn’t hurt,” said Tobe Berkovitz, associate professor emeritus of advertising at Boston University.

Harris’ background gives her an advantage at the start: “The common line from Republicans is that Democrats are weak on crime and being a prosecutor is a defense against that,” said Gibbs Knotts, professor of political science at Coastal Carolina University in Conway, S.C.

“Democrats are also already making the election about a prosecutor versus someone convicted of felonies, so that contrast appears to be poll-tested and working for Harris and against Trump,” said Christian Grose, academic director of the USC Schwarzenegger Institute.

That could have some appeal to what Knotts called the suburban voter who are “a little bit on the fence, fiscally conservative but bothered by some of the things Trump has done or said.”

The politics of prosecution

Harris is a veteran prosecutor, starting after she graduated law school in 1989. She was elected San Francisco’s district attorney in 2004, serving for six years before being elected the state attorney general in 2010. She’s shown repeatedly in public that she has a piercing, even powerful, way of questioning a witness.

Dating back to her first years as a deputy district attorney in Alameda County, fresh out of law school, “she was a fighter, she was tenacious, she was always prepared,” said Margo George, who worked as a public defender in the county at the time.

While relationships between prosecutors and public defenders are naturally contentious, George remembers Harris as “just a really hard worker and a hard fighter.”

Harris’ biggest challenge is that Republicans are going to use her record and style as a prosecutor selectively, particularly three moments in her career when her tough talk wasn’t always popular, and arguably hurt her politically.

San Francisco: No to the death penalty

Early in her career as a prosecutor – during her run for San Francisco District Attorney – Harris pledged never to seek the death penalty. It was the same position her predecessor had taken and, while novel, wasn’t groundbreaking.

But the stance became a crisis for Harris when then-Sen. Dianne Feinstein, at the funeral for a police officer murdered by an AK-47, called on her to seek the death penalty for the cop’s alleged killer.

Other state and local leaders piled on, from Sen. Barbara Boxer to the city’s police chief. But Harris did not change her position.

Later, it proved to be a politically popular move among constituents, with one poll after the incident showing 70% of San Francisco voters supported Harris’ decision.

But it was less popular across the rest of California and became a defining factor in her 2010 race for state attorney general. She won by less than one percentage point against Republican Steve Cooley, then the DA of Los Angeles. It became the closest race of her career.

Her decision not to seek the death penalty against the accused police killer – who was eventually sentenced to life in prison without parole – lost her support among influential law enforcement groups and made her a target for attacks during the campaign.

In the two decades since, Harris has remained a staunch opponent of the death penalty.

“I appreciate where her stance was on that,” said Tinisch Hollins with the criminal justice reform group Californians for Safety and Justice. ‘“There’s some consistency in the recognition of overrepresentation of Black and brown folks in the system, and specifically those who are on death row.”

Still, Hollins — who is from San Francisco and worked as a young organizer while Harris was DA — said the vice president has a mixed record on criminal justice broadly.

As DA, Harris created a successful program that reduced recidivism. Her office also prosecuted a case that led to a man, Jamal Trulove, being wrongfully convicted and incarcerated for six years. Trulove’s conviction was later overturned and he received a $13 million settlement.

“She billed herself as a progressive prosecutor and I think she tried to be in some areas, but I do think that she definitely leaned on the pro-incarceration agenda,” Hollins said.

In an election where public safety is a big issue nationally, Harris has a record to run on.

“She does have a record of fighting crime and making communities more safe. That’s the sort of thing that’s going to be welcome to voters overall going into the fall,” said Democratic strategist Bill Burton.

Hollins said some voters of color, including herself, are skeptical of that record, though, and that Harris must still earn support from communities who have been hurt by the criminal justice system.

While having a Black woman as a candidate for the nation’s highest office is important, she said it doesn’t automatically win Harris enthusiasm from all Black voters.

“I hope to hear specifically if her policy platform includes things that are going to improve outcomes for Black Americans and the criminal justice system,” Hollins said.

U.S. Senate: Taking on Brett Kavanaugh

Harris in 2018 had been in the Senate for about a year and a half and was largely unknown outside of California. First impressions on a national stage often become lasting impressions, and Harris left an indelible one.

Trump had nominated Brett Kavanaugh to become a Supreme Court justice. It was a highly controversial pick, not just because his conservatism rankled Democrats, but because of accusations of sexual assault in his past.

Harris was relentless during her time to question him at the Senate Judiciary Committee confirmation hearings. She brought up abortion rights.

“Can you think of any laws that give government the power to make decisions about the male body?” she asked. Kavanaugh looked puzzled.

“I’m happy to answer a more specific question,” he said.

“Male versus female,” Harris said.

Kavanaugh finally said he was “not thinking of any right now.”

Social media exploded, pro and con on Harris.

The two also clashed over special counsel Robert Mueller’s look at the 2016 presidential election.

Harris asked if Kavanaugh had had discussions about the investigation with anyone at the New York law firm started by Trump’s personal attorney.

“Are you certain you’ve not had a conversation with anyone at that law firm?” she asked.

Harris repeated the firm’s name.

“Yes or no?” she asked. “I’m asking you a very direct question, yes or no?”

Kavanaugh would not say. Harris kept asking.

“How can you not remember whether or not you had a conversation about Robert Mueller or his investigation with anyone at that law firm?” she asked.

She figured, “I think you’re thinking of someone and you don’t want to tell us.”

Conservatives erupted with anger and are still furious about the exchange. Shortly after the two sparred, Trump told Fox Business “She was so angry and (demonstrated) so much hatred with Justice Kavanaugh.”

The exchange is seen by some analysts today as Harris playing too rough with people she disagrees with.

“That played beautifully to the Democratic base. But who needs to play for the Democratic base if you’re the Democratic nominee?” asked Berkovitz.

Presidential candidate: Tough debate

Harris had entered the 2020 presidential race looking formidable. Her announcement speech in her native Oakland drew an estimated 20,000 people.

Democrats around the country were eager to know more about a woman who had won three times in the nation’s biggest, most diverse state, and was a self-described “top cop.”

When the presidential candidates debated in June 2019 Harris stood out, but not in any way that helped her.

Joe Biden had said earlier that year that he had a knack for getting things done in the Senate, even if it meant working with supporters of segregation. Harris was critical of the comments, and said at the debate that Biden had opposed busing students to achieve integration.

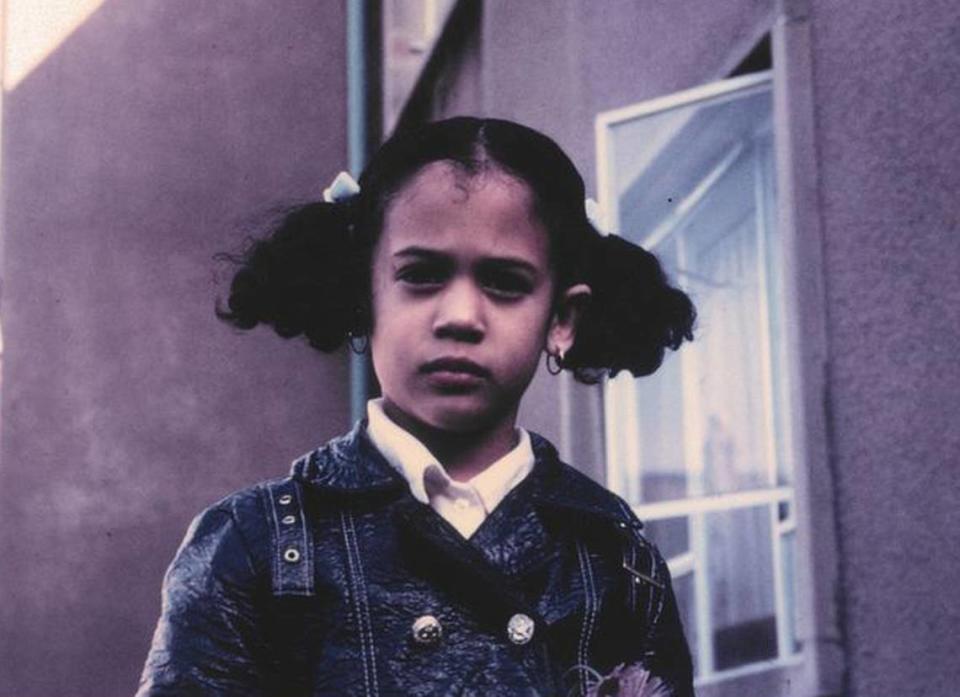

“There was a little girl in California who was part of the second class to integrate her public schools, and she was bused to school every day, and that little girl was me,” Harris said.

“I will tell you that on this subject, it cannot be an intellectual debate among Democrats. We have to take it seriously. We have to act swiftly.”

Her campaign that night put a photo of Harris as a child on Twitter.

Biden countered he did not oppose busing. “What I oppose is busing ordered by the Department of Education,” he said, and then recited his record on civil rights. Biden is highly respected among black lawmakers in Congress.

“If we want to have this litigated on who supports civil rights, I’m happy to do that,” Biden said.

The exchange was one of many reasons her presidential campaign went nowhere. She was out of the race by December 2019.

The exchange at the time was a reminder that “her prosecutor record was not seen as a strength,” said Jacob Rubashkin, deputy editor of nonpartisan Inside Elections, which analyzes political races.

But, he said, “We’re in a different moment now. We’re not in a Democratic primary.”