Researchers claim they obtained first-ever video of shark being struck by boat

Footage of the shark being struck by the boat can be viewed in the video player above.

Scientists with Oregon State University tracking sharks in the Atlantic Ocean say they have the first-ever video of a shark being hit by a boat.

Back in April, researchers with OSU’s Hatfield Marine Science Center tagged a basking shark – the second largest known fish in the ocean after the whale shark – off the coast of County Kerry, Ireland.

Just hours after marine life experts tagged the shark with an activity measurement device and camera “similar to a FitBit,” the female shark – said to be about 23 feet long – collided with a boat, as seen in the footage when the camera begins to tumble due to the force of the crash. The owner and operator of the vessel are not known.

According to Taylor Chapple, an assistant professor with Oregon State’s College of Agricultural Sciences, large marine animals being struck by boats is a “rising concern.”

Thus, the video footage – which Chapple believes is the first of its kind – provides researchers with a unique opportunity to learn more about how large marine life is impacted by vessel strikes.

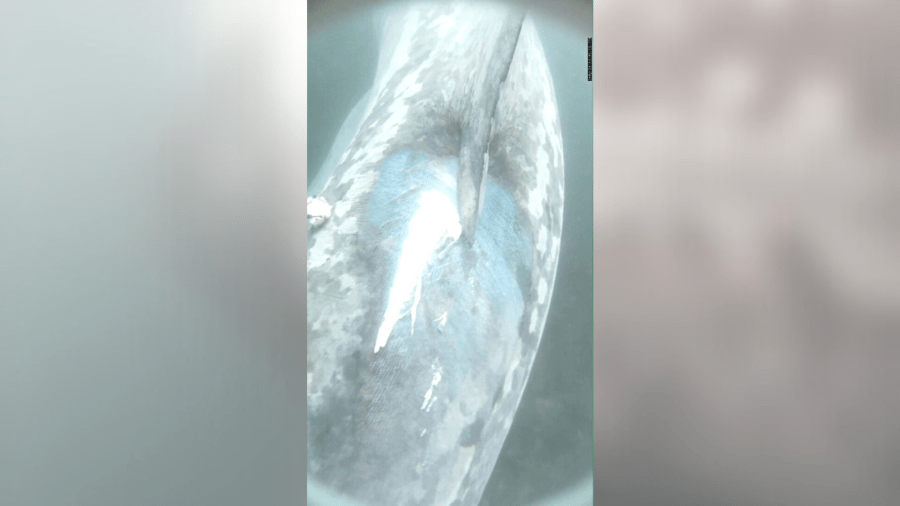

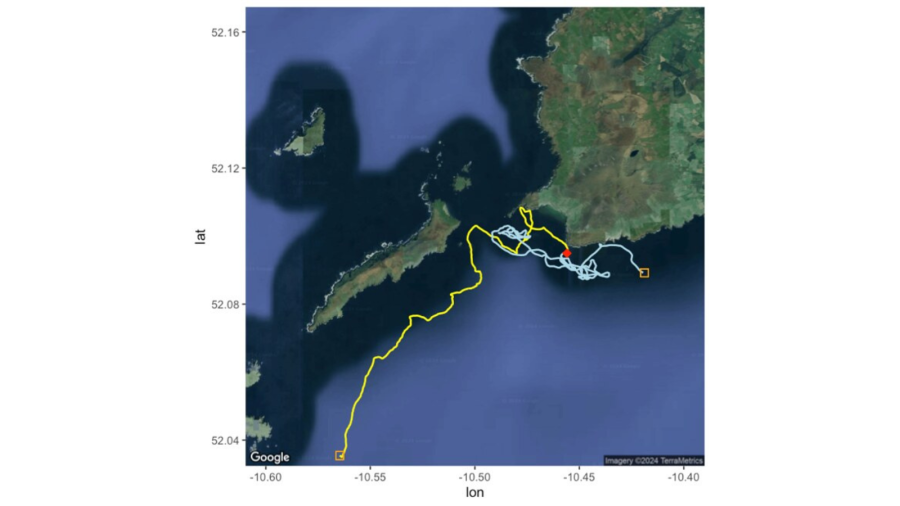

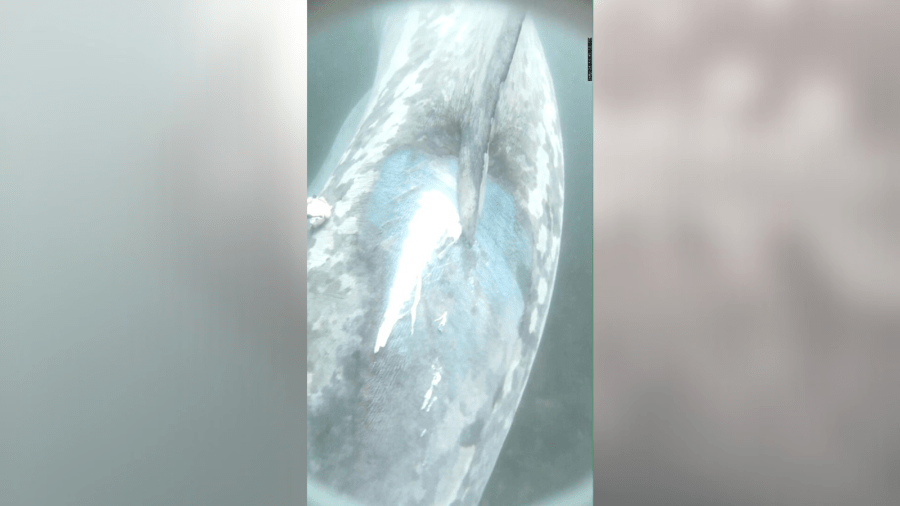

The keel of a vessel the moment it strikes the tagged basking shark. (Photo courtesy: Big Fish Lab, Oregon State University) Paint and abrasion can be seen on the shark after it was struck by a vessel. (Photo courtesy: Big Fish Lab, Oregon State University) A basking shark is seen shortly after it was tagged. (Photo courtesy: Big Fish Lab, Oregon State University) A graphic showing the path of a basking shark from the time it was tagged, then struck by a vessel and then where it was when the tag released. (Image courtesy: Big Fish Lab, Oregon State University)

“This if the first-ever direct observation of a ship strike on any marine megafauna that we’re aware of,” Chapple said. “The shark was struck while feeding on the surface of the water and immediately swam to the seafloor into deeper offshore waters, a stark contrast to its behavior prior to the strike.”

Data from the tag indicated that for several hours following the tagging, the shark spent most of its time on the surface continuing its normal feeding process before making a “quick, decisive movement” that was followed by the keel of a boat cutting across its back, just behind its dorsal fin.

Video shows visible damage to the shark’s skin, paint marks and a red abrasion but no apparent bleeding or open wound. And while vessel strikes are not always immediately lethal, researchers say the injury sustained by the shark could have short- or long-term effects.

Simone Biles shakes off calf injury to dominate during Olympic gymnastics qualifying

The tag was designed to record data autonomously until its scheduled release and was recovered about seven hours after the boat struck the shark; the data showed that the shark “never resumed feeding or other normal behavior” after the collision, and researchers noted that it remains unknown if she eventually recovered or not.

Basking sharks, Chapple says, filter feed at the water’s surface, making them more susceptible to being struck by boats. However, unlike whales, basking sharks often sink when killed, making it challenging to gauge death rates.

The species is listed as vulnerable by the International Union for Conservation of Nature, and the waters off County Kerry, Ireland, are one of the only known locations worldwide where they continue to aggregate in large numbers, scientists say.

“This research raises additional questions about whether and how often the sharks are actually occupying such habitats when they are not clearly visible at the surface,” said study co-author Alexandra McInturf, a research associate at Chapple’s OSU Big Fish Lab and co-coordinator of the Irish Basking Shark Group. “Given that Ireland is one of the only locations globally where basking sharks are still observed persistently, addressing such questions will be critical to informing not only our ecological understanding of the basking shark, but also the conservation of this species.”

Oregon State University’s Hatfield Marine Science Center is a research and teaching facility located on the Yaquina Bay estuary in Newport, Oregon. The laboratory serves as a base for resident scientists to conduct oceanographic studies and provide instruction; in addition to OSU students and researchers, the Hatfield Center also includes research activities from five different state and federal agencies.

The full study, which was published in the journal Frontiers in Marine Science, can be read here.

Copyright 2024 Nexstar Media, Inc. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed.

For the latest news, weather, sports, and streaming video, head to KTLA.