Sleepless nights, blazing tents: Sacramento heat wave tests limits of those without AC

This week in their East Del Paso Heights home, Maria and Pedro Magaña have had trouble falling asleep before 2 a.m. The house is too hot in the evenings, because central air conditioning to cool the house during the day is simply beyond their budget.

They’re making do with window cooling units, one in their bedroom and another in that of their 13-year-old son. From the early evening until the late into the night, they alternate turning one on each hour or so to conserve energy and save costs.

“It’s difficult to sleep,” said Maria Magaña on the couch in her living room, a ceiling fan spinning above her.

July 4th is her birthday, an occasion typically celebrated by cooking and gathering with family and friends at home. But with temperatures forecast to hit 108 degrees Thursday, she worries that may not be possible.

“This is something we have to cope with,” said her husband, who works as a custodian at Twin Rivers Unified School District, about the heat’s burden on their day to day lives. “It’s not that we like this situation, but we’re used to it.”

The Magañas struggle to stay cool is a glaring reminder that extreme heat is not shared equally in Sacramento and cities like it. Instead, it’s often suffered in silence by people with the least resources to handle it and most at risk of accompanying health threats.

Low-income families, the elderly and homeless adults are the most vulnerable to heat, the deadliest symptom of climate change. While plans, funding and programs to fight this crisis are revving up, advocates warn the response continues to be insufficient.

Hermán Barahona, lead community organizer and founder of the Sacramento Environmental Justice Coalition (SacEJC), said the dire circumstances he’s seeing on the ground are in no way reflected in government responses to the problem.

“Very low income communities of this state are not being included in these temperature standards or climate action plans. If they did we’d have an emergency response program for the calamity these people are experiencing,” he said.

“It’s a survival game out here.”

Sacramento’s heat islands

The entrance of Nikki Buckles’ tent near Del Paso Park reached 147 degrees, a thermometer showed Tuesday. That’s not a typo — 147 degrees Fahrenheit.

Temperatures in Buckles’ part of the city are hitting well above 100 degrees for a multiple day stretch, with nearly 70 degree nighttime low temperatures offering little relief from daytime heat.

The Sacramento native fell into homelessness after a house fire and fell into a financial hole during the pandemic, but he hopes housing is around the corner. A former carpenter, he mounted an AC unit to his tent so one part stays below 90 degrees.

For all his handiness, the unit in his tent isn’t cutting it this week. When the lethargy and nausea of heat exhaustion hits, he said, he lays still as possible in the cooler part of his tent to fend off heat stroke. He said he sometimes passes out for hours at a time.

Buckles said that on Wednesday, he’ll probably do something he’s never done before: abandon his possessions and go to a cooling center. It’s a decision he’s mainly making for the safety of his dog.

If it weren’t for the motivation to keep his pet safe and healthy, he said the stressors of surviving through brutal heat waves like this one would make him want to give up. He can’t remember a summer this hot.

“I find myself wanting to give up on a daily basis,” said Buckles. “I grew up here and summers were always hot but they were tolerable. I never remember temperatures being this high.”

Heat waves are a natural part of Sacramento’s climate. But scientists agree that atmospheric warming caused mainly by burning fossil fuels has already increased the frequency, intensity and duration of heat spells in the American West.

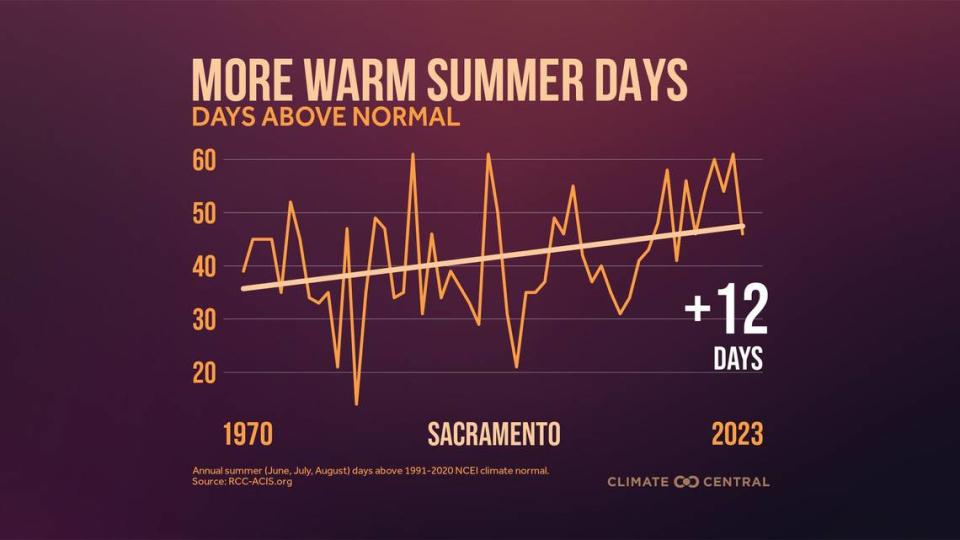

Sacramento now sees an average of 47 days per year of above-normal summer temperatures, compared to 35 in the 1970s. That’s according to data crunched by Climate Central, a national climate research and communications organization.

Climate Central reported that this week’s local temperatures were made five times more likely by climate change, based on an estimate that compared current temperatures to a hypothetical atmosphere without fossil fuels.

Over the next three decades, the number of extremely hot days in the city could triple, according to a report by the Natural Resources Defense Council, increasing the potential number of deaths from heat-related illnesses.

All that means extreme heat is here to stay, but it is not felt evenly across the city.

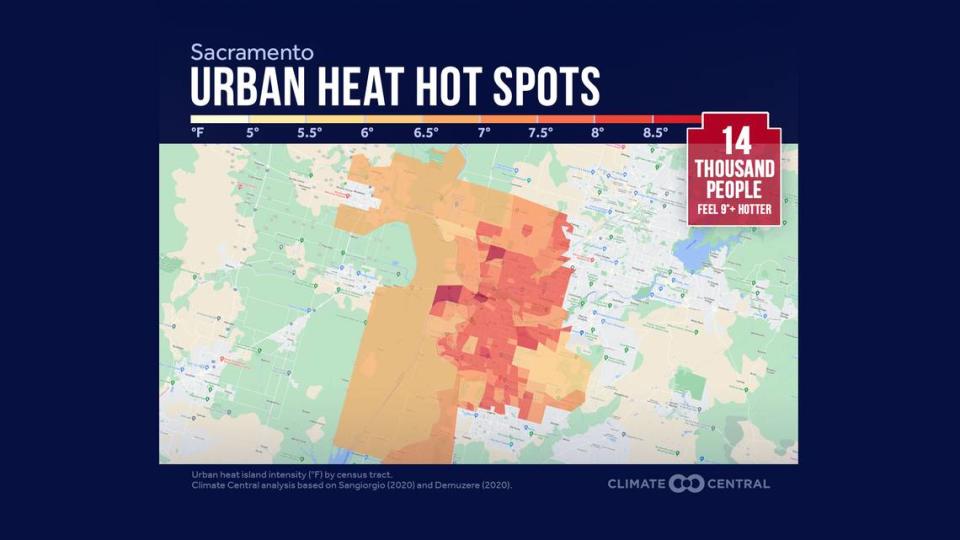

More than half of Sacramento’s population lives in areas that feel roughly 9 degrees warmer than neighboring areas, researchers have found. The phenomenon is called “urban heat island effect.”

Especially hot areas include downtown, West Sacramento, North Natomas and neighborhoods of South Sacramento. Not surprisingly, these hot areas are lacking in tree cover. Like many cities, the disparity tracks with income.

Peter Girard, a spokesperson for Climate Central, said heat map in Sacramento and cities across the nation tends to reflects the legacy of systematic racism. There are people whose lives are unaffected by brutal heat, and those whose lives are threatened by it.

“When you look across cities, it is frequently aligned with redlining maps where you saw neighborhoods suffering from a lack of investment,” Girard said. “The extreme heat that you see more frequently with climate change is remarkably inequitable.”

Responding to extreme heat

Climate scientists say extreme heat is the most deadly symptom of climate change and governments are slowly beginning to treat heat like a public health crisis. But actually connecting vulnerable populations to helpful services has proven slow.

In 2022, Gov. Gavin Newsom released an Extreme Heat Action Plan that pledged $300 million towards adapting to the state’s warmer reality. Extreme heat is also likely to be on the ballot this November in the form of a climate bond.

Last month, California regulators passed rules to protect workers from rising indoor temperatures, a measure that applies to all employers except state prisons and local jails, and will particularly protect workers in warehouses and restaurant kitchens.

But residential protections to set maximum indoor temperature rules for landlords and home sellers remain in flux, undergoing study by University of California researchers after years of opposition by rental housing industry associations in the state legislature.

Locally, Sacramento County opened a total of nine cooling centers, including one at the North A homeless shelter. Public libraries across the county also act as a de-facto cooling centers, but can be closed on holidays and weekends.

The county is still working on a final version of its climate action plan, which will include its overarching policy goals to address extreme heat. The draft plan highlighted by a county spokesperson mentions inequitable access to adequate cooling several times.

Pedro Magaña, the homeowner in East Del Paso Heights, said he hopes state and local agencies respond faster to climate change and help the working poor access cooling — so Sacramento’s privileged residents aren’t the only ones comfortable during a heat wave.

“The government should do more,” he said. “Working people are the ones that are out there in the fields or doing everyday jobs that sustain society. They deserved to be valued for building infrastructure that helps everyone else survive.”