Oil and gas wastewater is changing the Earth's surface, study finds

The U.S. oil and gas industry is having a visible effect on the Earth's surface, a new review of satellite images has found.

In recent years, energy companies have pumped an unprecedented volume of wastewater — a byproduct of fracking and conventional drilling — deep into underground wells. The water often can't be reused or recycled for economic or technical reasons, so many companies have found it easier to inject the water back into the ground.

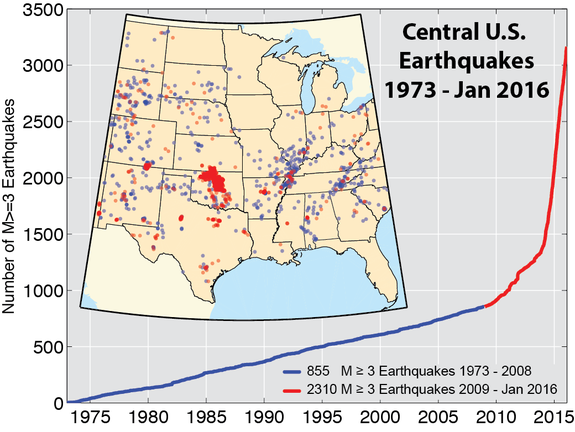

That process has sparked a wave of earthquakes across the central United States, transforming the Earth both above and below the surface, according to a study published Thursday in the journal Science.

SEE ALSO: Oklahoma's magnitude 5.8 quake comes amid concerns around oil and gas boom

Wastewater not only puts pressure on underground fault lines, causing "induced" earthquakes, but also pushes up the surface of the ground — a phenomenon called "uplifting" that can be seen from space.

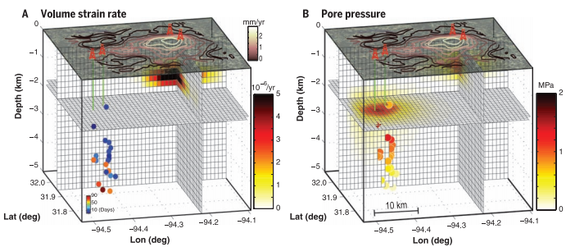

Researchers used satellite images of ground uplifting to show how wastewater disposal in eastern Texas eventually triggered a magnitude-4.8 earthquake in May 2012, the largest earthquake recorded in that half of the Lone Star state.

Image: AP Photo/Sue Ogrocki

"We brought a new angle to this study of 'induced seismicity,' which is monitoring the seismicity from space," said Manoochehr Shirzaei, the study's lead author and a geophysicist at Arizona University's School of Earth and Space Exploration.

"This hasn't been done before," he told Mashable.

The team studied surface changes near two sets of wastewater disposal wells separated by less than 15 kilometers, or about 9 miles. Using satellite-based observations from 2007, 2010 and 2014, the researchers estimated the evolution of local "pore pressure" — the pressure of fluids within the pores of a subsurface rock.

Shirzaei said they estimated the pore pressure changes were strong enough to cause earthquakes, including the 2012 temblor near Timpson, Texas.

Image: Science magazine

The Science study comes as U.S. researchers are racing to understand how years of injecting wastewater is causing damaging earthquakes in areas that previously saw little, if any, seismic activity.

Oklahoma, for instance, experienced more than 900 earthquakes of magnitude 3.0 or greater in 2015, according to the Oklahoma Geological Survey (OGS), a state agency. That's up from just one to two per year in the decades prior to the state's drilling boom.

Earlier this month, the state saw a magnitude-5.8 earthquake near the town of Pawnee, the largest recorded temblor in Oklahoma.

The Sept. 4 earthquake, which occurred along an unmapped fault line, is stoking fresh fears among some scientists that Oklahoma's wastewater wells could trigger other unknown faults.

Scientists at OGS recently suggested that a large "pulse" of oil and gas wastewater created over the last few years may be moving deep underground, boosting the risk of seismic activity even as regulators adopt new restrictions on wastewater injections.

"How long can we expect that pulse to raise the chances of having a damaging earthquake? That's an area that requires further research," Robert Williams, a geophysicist with the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) in Golden, Colorado who is unaffiliated with the new study, told Mashable.

Image: U.S. Geological Survey.

Williams coordinates the USGS earthquake program in the region of Oklahoma and the eastern U.S. He said that the agency now spends roughly $3 million a year to study the causes and impacts of human-induced earthquakes, up from annual spending of just a few hundred thousand dollars a few years ago.

Shirzaei said that, going forward, satellite-based observations could help oil and gas companies find safer places to inject their wastewater underground.

The researchers developed a forecasting model that factors in where fluids would be injected and at what volume and pressure. The model forecasts how much the Earth is likely to change under the surface and where and when uplifting might occur.

Shirzaei said this preventative approach is better than restricting or stopping oil and gas wastewater injections. Given the economic and political importance of U.S. oil and gas drilling, he said disposing of wastewater would continue to be necessary.

"The goal is to make this part of the routine procedure for wastewater injection...to make the injections safer and to minimize the number of earthquakes," he said. "We have to do it, and we have to do it safer."