Pesticide ban cuts South Korea's high suicide rate - a bit

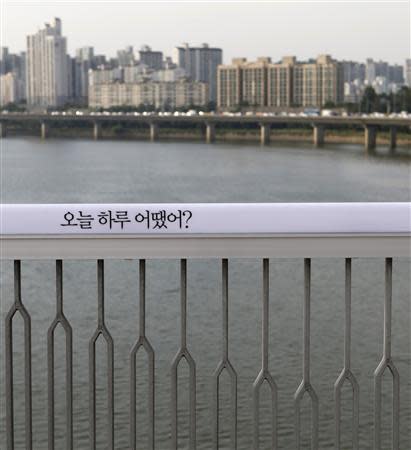

By Ju-min Park SEOUL (Reuters) - Jang Chang-yoon was drunk and weepy one rainy night, troubled by debts from his divorce. On a dark impulse, the South Korean waiter bought a bottle of pesticide to end it all with a few toxic swigs. At the last minute, he changed his mind when his young daughter grabbed his arm and begged him: "Daddy, don't die." Unlike Jang, many people do not pull back from the brink in South Korea, which has had the highest suicide rate in the developed world for nine straight years, often drinking pesticide as their way out. But a decade after Jang's brush with death, a ban on fatal pesticides is credited with cutting the number of suicides by 11 percent last year, the first drop in six years. The government restricted production of Gramoxone, a herbicide linked to suicides, in 2011 and outlawed its sale and storage last year. "The number of suicides by poisoning including Gramoxone fell by 477, which accounts for about 27 percent of the total decrease in the number of people committing suicide," Lee Jae-won, an official at Statistics Korea, said last week after the government released the latest figures. Pesticide was the method of choice for almost a quarter of the South Koreans who killed themselves between 2006 and 2010, according to a government report to parliament. In the highly competitive society of Asia's fourth-largest economy, experts say people who end up alone battling pressure for good school grades or from financial burdens have little in the way of a safety net. Despite the improvement in the suicide rate, more than 14,000 South Koreans killed themselves last year. Elderly people living in rural areas are a particularly high-risk group. Since the 1950s, older generations have been fixated on South Korea becoming more competitive and productive, a side effect of rapid industrialisation that turned a war-damaged country into one of the richest in the world. STIGMAS AND PAIN Kim Hyun-chung, a psychiatrist at the Korean Association for Suicide Prevention, sees social stigmas as a major reason for the high suicide rate. Many South Koreans who are depressed or under heavy stress are reluctant to bring up issues like mental illness or an inability to cope, he said. "The ban on toxic pesticides obviously led to the decline in the suicide rate because that is the easiest means of suicide for elderly people in rural towns," Kim said. "But we still have bridges and charcoal briquettes." To help limit access to lethal chemicals, the Life Insurance Philanthropy Foundation launched a campaign to provide pesticide lockers to farming towns with high rates of depression. The foundation, set up by private insurance firms, says no one from the villages with the lockers has committed suicide over the past three years, compared with one or two people from each village who had killed themselves in past years. "The lockers help reduce the impulse to get hold of pesticides because they have to find keys to open them," Chung Bong-eun, an official at the foundation, told Reuters. The 2012 figures may offer a glimmer of hope, but the latest comparisons by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development showed South Korea was by far the most suicidal society, followed by Hungary, Russia and Japan. For Jang, working two jobs is still tough, but he regrets trying to kill himself and is happy to have his life to share with his two daughters. While he sees the ban on pesticides as a positive step, he feels for others who are under duress. "Old and young people have their own pain from either quick economic development or unemployment," he said. "I hope the government will care more about people's health." (Editing by John O'Callaghan and Ron Popeski)