Puffing Billy keeps Australian steam train history alive

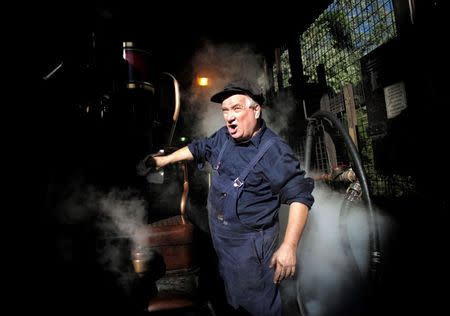

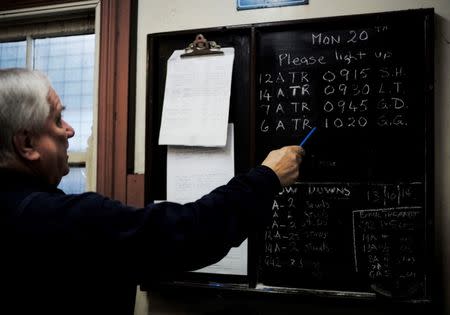

By Jason Reed BELGRAVE Australia (Reuters) - While the discovery of steam power 200 years ago drove the industrial revolution, the world long ago shunted most steam trains onto the sidings of history. But in one small corner of rural Australia, the sights, sounds and smells of the industrial revolution remain very much alive. In the picturesque Dandenong Ranges on the eastern outskirts of Melbourne, "Puffing Billy" is Australia's last full-time steam engine railway. "I grew up at the end of the steam era, I've been around the engines all my life," Puffing Billy driver Steve Holmes recently told Reuters in the locomotive shed at Belgrave. "We're not only just preserving the equipment, we're preserving the skills and hopefully the traditions of the Victorian railways as well. If it's not done, it all gets lost.' The short railway - just 18 miles (29 km) long and built in 16 months during the 1890s - boasted Victoria's tightest railway curve and a maximum speed of a mere 15 mph (24 kph). Its quaint, almost toy-like nature would also prove its downfall. The need to transfer the crops and timber it carried onto larger, broad gauge trains made it financially untenable. Despite those losses and the rise of motor vehicles in the first half of the 20th century, Puffing Billy always enjoyed a loyal following with daytrippers, honeymooners and weekenders - until a large landslide covered the tracks and closed down operations in 1953. During a decade of decay and disrepair, public pressure to reopen the railway as a tourist endeavor built. In 1962, the railway was reborn, using mostly volunteer labor. More than 250,000 people a year now visit the railway. Holmes sees his work as paying homage to his late father Norm, a railway guard who introduced him and his brothers to the charms of the rails. Holmes' own son Murray is now employed full-time maintaining and rebuilding carriages in the workshop and Murray, like his elder brother Keith, are both volunteer locomotive fireman on the railway. "I’ve got to be still driving at age 72 so that my eldest grandson Anthony can be a qualified fireman so he can fire for me,” Holmes said. EARLY START The day starts before sunrise, with just one lit match bringing the 102-year-old locomotive 12A slowly to life, building a fire with expert care that takes about four hours and will eventually reach interior temperatures of more than 1,000 Celsius (more than 1,800 Fahrenheit). Sipping a cup of tea kept hot sitting on the firebox hob, Holmes and 70 year old fireman Barry Rogers get the all-clear and the 10 a.m. train packed with tourists rolls out of Belgrave station. Over the beat of the exhaust and the steam pressure safety valve popping off, Holmes speaks directly to the engine in lively conversation. "You talk to the engines but sometimes you can't print some of the things we say to them." Rogers is stoking more coal into the fire and feeding water into the boiler to maintain the steam pressure just at the sweet spot. He has it down to a science as the steam safety valve pops off right at the base of the next climb, signaling to Holmes that he has the maximum pressure available to attack the hill. Chugging through quaint Victorian whistle stops such as Emerald and Lakeside and Cockatoo, the shrill whistle and 1-2-3-4, 1-2-3-4 beat of the little loco bounces off the hillsides and for just a few moments the modern world pauses. Holmes is involved with others in a push to restore the railway's oldest locomotive 3A, languishing in the railway's workshop. "After all, the greybeards that want to see her running are not getting any younger." (Editing by Lincoln Feast and Robert Birsel)