You are responsible for melting this much Arctic sea ice per year

The next roundtrip flight you take from New York to Europe means you will personally contribute to the melting of 32 square feet of Arctic sea ice by September in a given year, according to a groundbreaking new study published Thursday.

Or to put it another way, in a given year, the average American melts about 538 square feet of Arctic sea ice at the end of the summer melt season.

The study, published in the journal Science this week, for the first time makes the link between individual actions in lower latitudes with the rapid, expansive changes taking place in the Arctic.

SEE ALSO: 'Not enough ice for a gin and tonic:' two weeks in the Northwest Passage

The new study is particularly resonant given that sea ice extent declined to its second-lowest level on record this year, and a sailing vessel managed to traverse the Northwest Passage without spotting any large chunks of sea ice at all.

The U.S.-German team of researchers responsible for the study found that about 3 square meters of summer sea ice disappear in the Arctic for every metric ton of carbon dioxide added to the atmosphere. They then used that relationship to translate the ice loss into the carbon footprint of our everyday activities, be it flying or taking a long, 2,500-mile road trip via car.

The study also explores the linear relationship between the amount of carbon dioxide added to the atmosphere over time and long-term changes in the average monthly sea ice area in September, which is when the ice typically reaches its annual minimum.

The researchers found that this type of relationship holds up best when studying the observational record of sea ice area from 1953 through 2015, and show it is likely to continue to hold in the future.

"We hope that this study will allow people to more intuitively grasp the mere fact that Arctic sea ice does not disappear because of some large-scale, anonymous action, but simply because of our little day-to-day activities," said study co-author Dirk Notz, a senior researcher at the Max Planck Institute for Meteorology in Hamburg, Germany, in an email to Mashable.

"Hence, the loss of Arctic sea ice really is our shared responsibility, which then also implies that we have the means to slow down and eventually stop that ice loss, for example by following the Paris agreement," he said.

A history of melting ice

The Arctic’s summer ice cover has shrunk by more than half during the past four decades, with a recent acceleration of this trend. The Arctic is warming at about twice the average rate of the rest of the world.

Arctic sea ice loss is also suspected to be altering the jet stream and leading to extreme weather events in the U.S. and Europe in recent years.

Climate models show that Arctic sea ice may be completely lost by mid-century unless stringent emissions cuts are enacted.

More specifically, the study found that additional cumulative greenhouse gas emissions have to remain under 1,000 billion tons (or 1,000 gigatons) of carbon dioxide in order to keep some Arctic summer sea ice cover.

In other words, our carbon bank account has 1,000 billion tons in it, and if we go over that, one of the many penalties we'll pay is in the form of a seasonally ice-free Arctic Ocean.

Image: Notz and Stroeve/Science Magazine

Losing it completely would alter the way of life for the people who call the Arctic home, as well as pose existential threats to iconic species such as the polar bear and walrus.

Currently, the world is on course to put far more carbon dioxide into the air than 1,000 billion tons, considering we are emitting between 30 and 40 billion tons of carbon dioxide per year. This means an ice-free Arctic Ocean during the summer months is possible as early as 2045, according to the study.

Some countries better than others

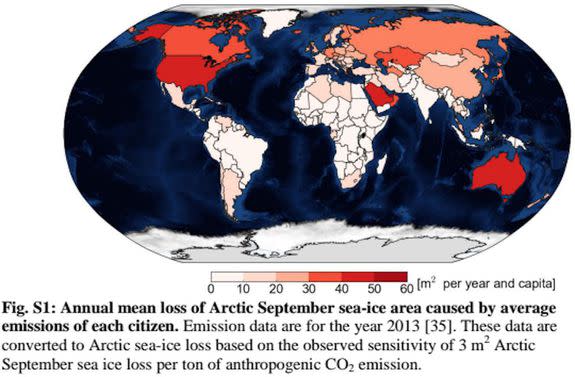

The researchers produced a map showing which countries' citizens are destroying the most sea ice, based on carbon emissions per capita.

Residents of the U.S. and the European Union, not surprisingly, were found to bear most of the responsibility when compared to growing developing nations like China and India, where emissions per capita are still lower.

For example, based on 2013 emissions data, the average American was responsible for destroying about 10 times the amount of sea ice compared to the average citizen of India.

"We also wanted to provide a more tangible way for policy makers to understand our contributions to sea ice loss, which is where the map idea came from," said co-author Julienne Stroeve, a senior researcher at the National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC) in Boulder, Colorado, and a professor at the University College London.

Need to stay below 2-degree limit

The study found that global warming would need to be held below 2 degrees Celsius, or 3.6 degrees Fahrenheit, compared to preindustrial levels by 2100 in order to have a good chance of maintaining some ice cover during the summer in the Far North.

Image: Polar ocean challenge

Walt Meier, who studies sea ice at NASA's Goddard Space Center and was not involved in the new study, said it is interesting work that contradicts the hypothesis that reinforcing or runaway feedback loops in the Arctic would cause a sudden acceleration of ice loss over time.

"This paper is further evidence against a tipping point and towards a more linear response. Of course, this is over the long-term — the paper looks at 30-year running means. Over the shorter term (several years), there is a lot of variability," Meier said in an email.

He added that the linkage of specific carbon dioxide emissions to ice loss amounts is a new, albeit "highly simplified" visualization of how human-caused climate change is reshaping the Arctic.

"Where this tying of [greenhouse gas emissions] to ice loss is probably most impactful is on policymakers and the general public," he said.

The study comes at a fortuitous time, since the next round of U.N. climate negotiations, during which the possibility of making more stringent emissions cuts will be on the agenda, begin in Marrakech, Morocco on Nov. 7.