As Sea Ice Melts, Storm Surges Batter Arctic Coasts

As each Arctic summer brings less sea ice, two new studies warn of major changes, from devastating storm surges to huge increases in shipping.

Rising temperatures in the Arctic — a result of global climate change — are bringing bigger and stronger storms, with hurricane-equivalent winds, previous research shows. And the region's dwindling sea ice cover (Sept. 2012 saw a record summer sea ice low, NASA reported) means storms can charge across the ocean without restraint.

Thick summer sea ice once slowed down Arctic storm winds, stopping them from generating high storm surges, the bulge of water that builds up ahead of a storm that can batter and flood a coastline.

One of the new studies tracked 400 years of storm surges in Canada's Mackenzie River delta, and found the wave-borne floods are becoming stronger and more frequent.

"I think it's another piece of the puzzle that suggests the Arctic is changing very rapidly and these changes are related to what’s going on with respect to climate change," said study co-author Michael Pisaric, a biogeographer at Brock's University in Ontario, Canada.

"Storms are growing larger and stronger, and there's so much more open water for these storms to blow across. These two [factors] combined are creating new conditions for the Arctic that when you put increasing infrastructure and exploration for hydrocarbons, that's starting to create a recipe for disaster," Pisaric told OurAmazingPlanet. Hydrocarbon exploration in the Arctic includes floating and fixed oil and gas wells. [8 Ways Global Warming Is Already Changing the World

The findings were detailed online Jan. 25 in the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

Flooding low-lying coasts

The Mackenzie River delta and its inhabitants are still struggling to recover from the shocking effects of a massive storm surge in 1999. Pisaric and his colleagues collaborated with Inuvialuit of the northwest Arctic to document changes since the 1999 storm surge.

"They alerted us to the fact that everything was dead out there," Pisaric said. Saltwater killed 37 percent of the region's plant life within five years, and the soil remains contaminated with high salt concentrations, a 2011 study found. Because no plants are growing to provide food, wildlife has moved away.

"The hunters and trappers were very clear they don't go to this region anymore," Pisaric said.

Sediment in the many lakes dotting the low-lying river delta record the history of storm surge floods, Pisaric said. In the past 400 years, the 1999 event was the biggest storm surge in the sediment layers.

"The story we're seeing is not just this region, but potentially other parts of the Arctic that are very low-lying could be susceptible to these types of storm surges," Pisaric said.

Storms and shipping

In terms of Arctic commercial development, bigger storms could hit more than just oil and gas companies. Shipping companies are also planning to take advantage of the Arctic's increasingly ice-free summers. In summer 2012, 46 voyages successfully crossed the Northern Sea Route, which runs along the Russian coast from Murmansk through the Bering Sea.

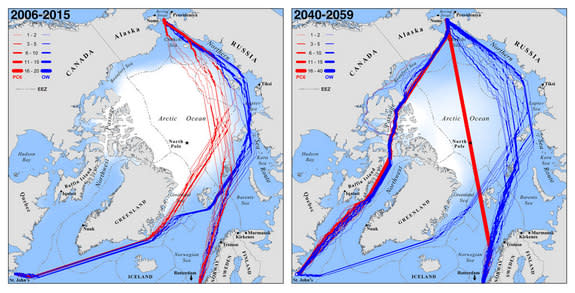

By 2040, even regular ships will sail parts of the Arctic Ocean, and they will not need icebreakers to clear the path as they do today, according to another study published today (March 4) in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

For the first time, icebreakers will be able to plow through the North Pole, making a straight shot from the Pacific to the Atlantic Ocean, the study predicts.

The projections have implications for port construction and extracting natural resources, the study authors, from the University of California, Los Angeles, said in a statement. Pisaric also said coastal storm surges could affect port development.

"Infrastructure that's rooted in the ground and can't move will bear the brunt of these storms, so ports could receive damage," he said.

Email Becky Oskin or follow her @beckyoskin. Follow us @OAPlanet, Facebook or Google+. Original article on LiveScience's OurAmazingPlanet.

Copyright 2013 LiveScience, a TechMediaNetwork company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.