The Sony Hack One Year Later: Just Who Are The Guardians Of Peace?

It was the most devastating cyber-crime ever committed against an American corporation, and its repercussions are still being felt not only in Hollywood but across the country and around the world. One year ago today, Sony Pictures Entertainment was hacked by shadowy terrorists calling themselves the “Guardians of Peace,” later identified by the FBI as operatives of the North Korean government.

The attack would come to involve the President of the United States, the FBI, the CIA, the State Department, the Department of Homeland Security and Congress, and yet little more is known about the identity of the hackers today than was known in those first few frantic days after the breach. That’s when blame first began to fall on North Korea, which was suspected of orchestrating the hack in retaliation for the studio’s planned release of The Interview, which ridiculed the Hermit Kingdom’s leader, Kim Jong-un. One year later, no arrests have been made, and none is ever likely; if it was North Korean operatives, they are far beyond the reach of U.S. law.

There were six communiques leading up to and following the Sony hack that have been attributed to the Guardians of Peace. At least one of them is now widely suspected to have been a hoax, and hackers claiming to be from the GOP say that another one is, too. In the three weeks following the attack, the GOP dumped seven huge, but difficult to access, caches of stolen Sony documents and emails onto online file-sharing hubs, and then quietly disappeared, never to be heard from again.

In April, WikiLeaks re-victimized Sony by posting the mountain of stolen documents for everyone to see.

Throughout it all, Sony stood up to its attackers and fought back as best it could, releasing The Interview digitally and in indie theaters in the face of threats against venues that showed it. The film grossed $6.1 million theatrically in limited release and $40M digitally – overall a loss on top of the $41 million the studio said it spent on the “investigation and remediation expenses” relating to the attack. But many of those who went to see the movie that Christmas weekend said they did so out of a sense of patriotism – a defiant act against the terrorists’ threats. In the end, the hackers didn’t get what they wanted: to instill fear into those who would criticize their “Dear Leader.”

For the many other U.S. companies and government agencies that have since been hit by cyber-attacks, Sony Pictures proved to be the canary in the coal mine. It is still dealing with the fallout. Ultimately, the hack led to the exit of film chairman Amy Pascal, who was replaced by Tom Rothman; the company continues to have its dirty laundry aired in publications all over the country after the WikiLeaks dump; and employees who watched in horror as their Social Security numbers and other personal information were made public will have to be watchful for the rest of their lives.

RelatedSony Hacking Class Action Lawsuit Reaches Settlement

The studio’s business has begun to rally recently, though, with Hotel Transylvania 2, Goosebumps and of course Spectre helping improve SPE’s market share. The stock of its parent company, Sony Corp, is doing fine, up more than 24% since the attack.

John P. Carlin, the Justice Department’s Assistant Attorney General for National Security, told Deadline that Sony Pictures’ response to the hack should serve as a model for all U.S. companies, and that Sony helped raise awareness of the threat cyber-criminals pose to everyone.

“In the Sony hack,” he said, “we saw a foreign, state-sponsored cyber actor wage a destructive attack to steal valuable information and inflict significant damage. Sony did the right thing: they reached out almost immediately to law enforcement and the FBI responded. Sony’s cooperation from day one is a model: it greatly aided the investigation and allowed us to, in unprecedented fashion, publicly name who did it in a very short amount of time.

“I think the Sony hack and response did more to raise national security cyber awareness than any other single event,” he continued. “The lessons learned from Sony have changed board practices across the country as companies examine whether they are ready to respond in a world where every company in every sector is vulnerable in a way they have not been before.”

Three days before the attack, hackers identifying themselves as “God’sApstls” sent an extortion demand via email to SPE co-chairs Pascal and Michael Lynton, and several other top studio officials. “We’ve got great damage by Sony Pictures,” the message said in broken English. “The compensation for it, monetary compensation we want. Pay the damage, or Sony Pictures will be bombarded as a whole. You know us very well. We never wait long. You’d better behave wisely.”

There was no hint in that message that North Korea was involved; indeed, calling themselves apostles of God would be strange coming from an officially atheist state. On the other hand, it may have been misdirection.

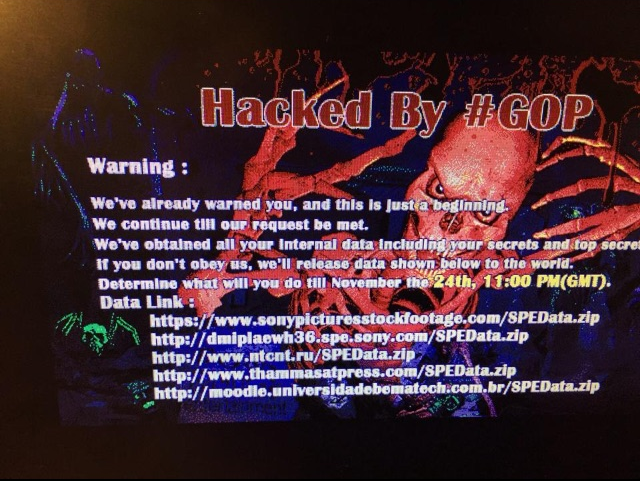

Three days later – on November 24, 2014 – the image of a stylized skull with long skeletal fingers flashed onto computer screens throughout the company, accompanied by a threatening message from the Guardians of Peace, written in the same broken English. “We’ve already warned you, and this is just a beginning. We continue till our request be met. We’ve obtained all your internal data including your secrets and top secrets. If you don’t obey us, we’ll release data shown below to the world.”

At 10:50 that morning, Deadline first reported the news that Sony Pictures had been hacked. Phones and e-mail service were paralyzed, as were all the company’s computers. The attack had begun, and it would continue to capture headlines for months to come.

The GOP’s message that day also contained a cryptic reference to God’sApstls, the group that had sent the extortion demand three days earlier. “Thanks a lot to God’sApstls contributing your great effort to peace of the world,” it said in the same broken English. “And even if you just try to seek out who we are, all of your data will be released at once.” It was the same threat, and it was probably the same group. The first message had not been made public before the second message was sent, so there’s no way that anyone but the Guardians of Peace could have known to thank God’sApstls for their “great effort to peace of the world.” Neither message, however, mentioned North Korea or The Interview. That would come later.

The first reports linking North Korea to the attack surfaced on Friday, November 28, four days after the hack. That same day, a North Korean website called The Interview “an evil act of provocation.”

Three days later, the FBI confirmed that it had launched an investigation, although it was still not known – not even by Sony officials – who was behind it. Two days later, on Wednesday, December 3, the studio said that a report by tech industry website re/code, which said North Korea had been identified as the source of the attack, is “not accurate.”

The FBI’s behavioral analysis unit quickly went to work studying the writing and diction contained in the GOP’s initial statement, comparing it to other statements that had accompanied other hacks known to have been carried out by North Korea, and came to the conclusion that it was “the same actors.”

FBI Director James Comey then assembled a “red team” of intelligence experts to track down the hackers. Like the FBI behavioral analysts, they too concluded that it was North Korea. “The tools in the Sony attacks bore striking similarities to a cyber-attack that the North Koreans conducted in March of last year against South Korean banks and media outlets,” Comey said on January 7, in his first and only public comment about the attack.

“We brought in a red team from all across the intelligence community and said, ‘Let’s hack at this. What else could be explaining this? What other explanations might there be? What might we be missing? What competing hypothesis might there be? Evaluate possible alternatives. What might we be missing?’ And we end up in the same place.”

Even so, the FBI still isn’t sure how the criminals first got into Sony’s computer system – at least, not that the agency is letting on. “We’re still looking to identify the vector,” Comey said back in January. “How did they get into Sony? We see so far spear phishing coming at Sony in September – as late as September of (last) year. We’re still working that and when we figure that out, we’ll do our best to give you the details on that, but that seems the likely vector for the entry into Sony.” To date, the FBI has either not found that vector, or isn’t sharing who it is.

One week after the attack, the Associated Press reported that some cyber-security experts were saying they’d found “striking similarities” between the code used in the hack on Sony and attacks blamed on North Korea which targeted South Korean companies and government agencies the previous year.

The next day, hackers claiming to be the Guardians of Peace e-mailed Sony employees another poorly worded threat, this time vowing to hurt them and their families if they don’t sign a statement repudiating the company. “Many things beyond imagination will happen at many places of the world. Our agents find themselves act in necessary places. Please sign your name to object the false of the company at the e-mail address below if you don’t want to suffer damage. If you don’t, not only you but your family will be in danger.”

That Sunday, North Korea denied any involvement in the hack, but praised it as a “righteous deed.”

The next day, another communique claiming to be from the Guardians of Peace warned the studio to “Stop immediately showing the movie of terrorism which can break regional peace and cause the War!” This letter, however, denied responsibility for the previous threat against Sony employees and their families.

That was either a lie, or the first sign that a copycat may have joined the fray. If so, it wouldn’t be the last time someone claiming to be the Guardians of Peace was a fraud.

A confidential Joint Intelligence Bulletin (read it here) issued on December 24 by the FBI and the Department of Homeland Security attributed all of these communiques, with a slightly different timeline, to the Guardians of Peace. That bulletin, however, also attributed a sixth and final communique to the Guardians of Peace that is now widely believed to have been a hoax. That last message, which the FBI said contained an “implied threat,” claimed to have a “gift” for CNN because of its “excellent” coverage of the Sony hack. A freelance journalist, who later took responsibility for the hoax – and offered considerable proof to substantiate his claim – later got a visit from the FBI.

In the end, the Guardians of Peace may never be identified or brought to justice, though President Obama hit North Korea with tough new sanctions in the wake of the attack, and hours later, the entire country’s Internet connection collapsed.

Sony Pictures, meanwhile, isn’t looking back. “The cyber-attack on Sony Pictures was an unprecedented event, for which there was no playbook,” Robert Lawson, the studio’s chief communications officer, told Deadline. “SPE leadership and staff rose to the challenge quickly and diligently to protect critical business processes and kept the business moving forward. The entire studio worked smart, fast and collaboratively, and as a result, never missed a day of production or a day of payroll. One year later, the studio is looking forward, not back.”

RelatedSony Hack: A Timeline

Related stories

Sony Slapped With Negligence Suit By Ex-VP On Hacking Anniversary

Matthew McConaughey Eyeing Adaptation Of Stephen King's 'Dark Tower'

Get more from Deadline.com: Follow us on Twitter, Facebook, Newsletter