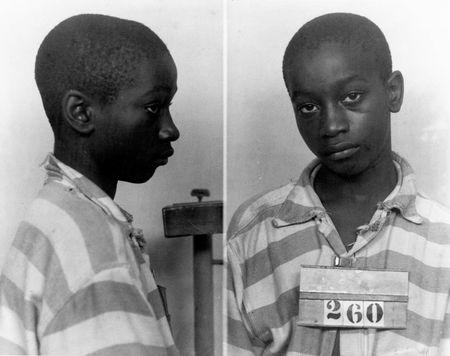

South Carolina judge tosses conviction of black teen executed in 1944

By Harriet McLeod CHARLESTON, S.C. (Reuters) - A South Carolina judge on Wednesday took the unusual step of vacating the 1944 conviction of a black 14-year-old boy, the youngest person executed in the United States in the past century, saying he did not receive a fair trial in the murders of two white girls. George Stinney Jr. was convicted by an all-white jury after a one-day trial and a 10-minute jury deliberation during a time when racial segregation prevailed in much of the United States. Stinney died in the electric chair less than three months after the killings of Betty June Binnicker, 11, and Mary Emma Thames, 7. In her ruling, Judge Carmen Tevis Mullen said she was not overturning the case on its merits, which scant records made nearly impossible to relitigate, but on the failure of the court to grant Stinney a fair trial. She said few or no defense witnesses testified and that it was "highly likely" that Stinney's confession to white police officers was coerced. "From time to time we are called to look back to examine our still-recent history and correct injustice where possible," she wrote. "I can think of no greater injustice than a violation of one's constitutional rights, which has been proven to me in this case by a preponderance of the evidence standard." The girls disappeared on March 23, 1944, after leaving home in the small mill town of Alcolu on their bicycles to look for wildflowers. They were found the next morning in a ditch, their skulls crushed. Stinney was taken into custody that day and confessed within hours, according to Mullen's ruling. Last year, members of Stinney's family petitioned for a new trial. His sister, Amie Ruffner, 77, testified in a January hearing that he could not have killed the girls because he had been with her on that day. Citing the lack of a transcript from the original trial, no surviving physical evidence and only a handful of official documents, Mullen ruled instead to overturn the conviction outright. Ruffner and two other surviving siblings of Stinney, who were run out of town shortly after his arrest, were pleased with the outcome, said Stinney family attorney Matthew Burgess. "This is something that's been weighing on them for seven decades now," he said. "They are happy to hear that their brother has been exonerated." Prosecutors, who had opposed a new trial, were not immediately available for comment. (Reporting by Harriet McLeod; Editing by Jonathan Kaminsky, Cynthia Johnston and Bill Trott)