Special Report: Elite law firms spin gold from getting cases before Supreme Court

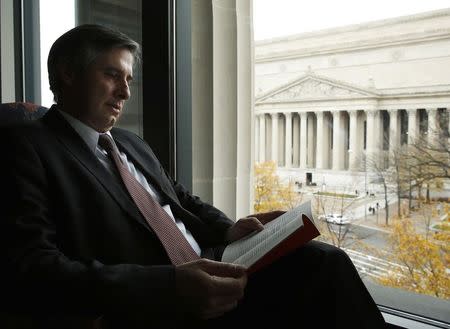

By John Shiffman, Janet Roberts and Joan Biskupic WASHINGTON (Reuters) - On a March morning in 2011, lawyer Ted Boutrous approached the lectern at the U.S. Supreme Court. Boutrous represented the world’s largest retailer, Wal-Mart , in one of the most anticipated business cases in years. A trial judge had certified a class of more than 1.5 million female employees who alleged systematic gender discrimination. If the women prevailed, Wal-Mart stood to lose tens of billions of dollars. Yet before Boutrous even began – “Mr. Chief Justice and may it please the Court…” – he had already succeeded in one significant way: As a result of his work on the case, Wal-Mart was becoming a premier client of his law firm, Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher. Today, Gibson Dunn handles real estate, securities, corporate, environmental and other legal matters for Wal-Mart – work that has generated more than $50 million in new revenues for the firm, say people familiar with the relationship. Gibson Dunn is not the only law firm to turn Supreme Court appearances into gold. After the firm Sidley Austin won a Supreme Court patent case for eBay, it earned at least $10 million in unrelated legal fees from the online retailer, say people with knowledge of the account. Likewise, the firm Jones Day secured Westinghouse/CBS as a major client following a successful high court case. In the years that followed, the relationship generated more than $10 million in fees, sources say. Securing profitable, long-term relationships with America’s largest corporations is one reason major law firms began creating Supreme Court practices in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Now, corporate firms so dominate the Supreme Court bar that they boast outsized access to a high court that’s already inclined to support corporations over individuals. A Reuters examination of about 10,300 court records filed over a nine-year period shows that lawyers at a dozen law firms, including Gibson Dunn, Sidley Austin and Jones Day, have become extraordinarily adept at getting cases before the Supreme Court. The news agency analyzed petitions filed by private attorneys, not those submitted by government lawyers or prison inmates and others who lack representation. Although the high court typically agrees to hear 5 percent of the petitions it receives from private attorneys, Reuters found that lawyers at the top dozen firms were successful 18 percent of the time. These firms were involved in a third of the cases the high court accepted, Reuters found. When the justices agreed to hear cases brought on behalf of Big Business, top firms were involved 60 percent of the time. A slightly larger group – 31 firms – accounted for 44 percent of all cases the court accepted. DISADVANTAGE FOR CONSUMERS The domination of the Supreme Court docket by firms that commonly represent business interests has a direct, largely unseen effect on consumers seeking to sue corporations: These individuals must select from a much smaller and, in many instances, less successful pool of lawyers to handle their cases. The reason: Many elite law practices won’t take those cases. The activities of the firms’ corporate clients are so broad, and their concerns so intertwined, that the lawyers point to disqualifying conflicts of interest – some specific, some general. An elite firm might refuse to represent an individual suing a corporation on a labor issue, for example, because it fears that winning the case could create a precedent that might hurt top clients in other industries. Large firms do take cases pro bono on behalf of the indigent. But those appeals are generally related to criminal law or social causes such as gay marriage – topics unlikely to affect U.S. business interests. “We do not take cases that could make negative law for our clients,” said Jones Day’s Glen Nager, who has argued 13 cases before the Supreme Court. The heads of several Supreme Court practices dispute whether public interest or consumer groups are truly disadvantaged when seeking effective counsel. “There are some practitioners out there who specialize in taking the cases the larger corporate firms can't take,” said Jonathan Franklin, a former law partner of now-Chief Justice John Roberts and head of the Supreme Court practice at Norton Rose Fulbright. “There is a sufficient pool of capable lawyers to take those cases, even if it's a smaller pool.” But for many of the top firms, such conflicts mean declining to represent environmental organizations, labor unions, employees suing employers, or consumers filing class actions; each kind of case might conflict with the general interests of their clients. “It’s not that there aren’t lawyers at these large firms who aren’t public-spirit minded and don’t want to do these cases. It’s that their business model won’t allow it,” said Joseph Sellers, a lawyer for the mid-sized firm Cohen Milstein, who argued against Wal-Mart at the Supreme Court. “In terms of access to justice, the ability of individuals to get their issues raised in the Supreme Court is more limited,” Sellers said. “Our side just doesn’t have the resources.” A POWER BAR At their core, Supreme Court practices, like many things in the nation’s capital, are about money and proximity to power. “If you want your firm to be viewed as a Washington institution, you have to have a Supreme Court practice,” said Pratik Shah, who leads the group at Akin Gump. Chris Landau agrees. From his office, he has one of the best power views in Washington, looking directly toward the eastern side of the White House. When he works late, Landau can watch the president’s helicopter lift off into the sunset. On the windowsill before this vista, he has placed an autographed picture of himself standing beside Justice Clarence Thomas. Landau runs the Supreme Court practice at Kirkland & Ellis, one of the older and most profitable law firms in America. His career arc, as well as the evolution of his firm’s high court practice, is typical of peers. Landau graduated from Harvard Law School. He clerked for Thomas and for Justice Antonin Scalia, and joined Kirkland’s appellate practice in 1993, the same year as former Solicitor General Ken Starr. The evolution of specialized, corporate-focused Supreme Court practices at Kirkland and other firms came as the justices began taking fewer cases – from about 150 annually in the 1980s to half as many today. That makes competition among lawyers fierce: More than 500 attorneys in Washington tout Supreme Court expertise on firm websites. “It’s a very cutthroat environment,” Landau said. Often, several veteran lawyers said privately, landing a Supreme Court case is almost as important to their firms as prevailing in court. On website biographies, lawyers and firms routinely list the number of Supreme Court arguments they’ve made and briefs they’ve filed; rarely do they list a win-loss record. Simply appearing before the top court brings with it prestige and publicity that firms believe help them recruit new corporate clients and lure the next generation of top attorneys. Most firms brand these lawyers not only as Supreme Court specialists but as appellate experts. Almost all of the lawyers, including Landau, spend more time arguing in U.S. courts of appeals, one rung below the Supreme Court. They assist partners in trial courts, and the firms work outside of the courtroom, advising corporations and trade associations on regulatory matters. With Congress gridlocked, the court’s role has become more prominent, so much so that the nation’s most influential business lobby, the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, has hired five former Supreme Court clerks. Supreme Court cases themselves aren’t usually as directly profitable as other types of litigation because they generally require fewer lawyers and less research. By contrast, trial and due diligence can involve teams of lawyers to review reams of paperwork and evidence. In just one month, a large trial can generate $1 million or more in fees. Firms typically charge far less to handle an entire Supreme Court case: The bill might range from $50,000 to $500,000 but has, in some cases, reached beyond $1 million. Besides petitioning the court to have cases heard, the top firms file “briefs in opposition,” aimed at dissuading the Supreme Court from granting an appeal if the client won in the lower court. They also frequently file “friend of the court” or amicus briefs. Most top firms submitted several dozen opposition and amicus briefs during the period Reuters examined. Records show their focus seldom varied: Whatever the type of brief, it largely reflected the interests of corporate America. Like other firms that dominate the Supreme Court bar, Landau’s Kirkland clients are almost exclusively corporations. He has represented Morgan Stanley, BP, Dow Chemical, ConAgra Foods, Raytheon, Nationwide Mutual Insurance, Motorola, W.R. Grace and Union Carbide. The roster of clients makes Kirkland extremely unlikely to represent an individual suing a corporation, Landau acknowledged. “The last thing we want,” he said, “is to make one of our long-standing clients unhappy with what we do.” ROLE REVERSAL Increasingly, the elite Supreme Court practices at firms are led by rainmakers, lawyers who have parlayed their government service into private sector profit. These lawyers are advocates not lobbyists, but they use their skills, experience, influence and connections in similar ways. At the very top are many former solicitors general and their assistants. These attorneys gain unsurpassed experience before the Supreme Court by arguing on behalf of the federal government. Some solicitors general have argued scores of cases. Because this advocate has such a close relationship with the court, the solicitor general has sometimes been called the 10th justice. Six former solicitors general now play a major role in a Supreme Court practice in Washington. Another recent solicitor general, Elena Kagan, is the court’s newest justice. Firms and clients covet former solicitors general because they are consummate government insiders. To prepare to appear before the justices, solicitors general and their assistants meet face-to-face with senior officials throughout the government. They are often wooed by special interest groups that have stakes in cases. Law firms also use lawyers with solicitor general experience to pitch regulatory and legislative work to clients. It is not unusual for a firm handling a Supreme Court case to remain involved long after a decision is issued, as lower courts implement the ruling and as the losing side lobbies Congress to alter or reverse it. Mayer Brown’s Andrew Pincus, for example, frequently appears before all three branches of government. A former assistant solicitor general who has argued 23 Supreme Court cases, Pincus regularly files regulatory comments, testifies before Congress and writes remarks for others on his areas of expertise – antitrust, securities, patent, arbitration and financial issues. Sometimes, he testifies or advocates on behalf of business interests generally, sometimes on behalf of specific clients. “I tell clients that the same skills I use at the Supreme Court – oral arguments and writing briefs – can be brought to bear elsewhere in government,” Pincus said. As demand for specialization increases and the elite Supreme Court bar shrinks, some corporations now compete against one another to secure the top lawyers. During his stints as the top attorney at Aetna and CBS/Westinghouse, Louis Briskman hired outside counsel in more than a half dozen Supreme Court cases from 1989 to 2013. “It’s radically changed in the last 10 years,” Briskman said. “Back then, you looked for a specialist in an area of the law. Now, you are not going to go with the specialist who won for you at the trial court in Pittsburgh. You want the guy who knows the justices and the justices know. There are 12 lawyers and firms that keep coming up.” Briskman said that the dozen includes two advocates he retained for Aetna and CBS: Miguel Estrada of Gibson Dunn and Paul Clement of Bancroft PLLC. Clement is a former solicitor general, and Estrada is a former assistant in the office. As cases move from trial to appellate courts, corporations often try to box each other out by retaining firms with superstar lawyers. “These days,” Briskman said, “before you even finish your circuit appeals, the other side has already put down money on an Estrada or a Clement.” SHAPING THE LAW Law firms have different goals than advocacy groups – profit, for one – but their Supreme Court practices often share an ideological interest in shaping the law for clients. For firms that are most active before the high court, those clients are more often than not corporations. The Wal-Mart case illustrates not only how a Supreme Court victory helped a firm secure future business, but also how firms look for ways to use the high court to benefit all their corporate clients. For Ted Boutrous, the route to the Supreme Court lectern in 2011 began decades earlier. As early as 1989, Boutrous and mentor Ted Olson began advocating for change on behalf of business to the courts, media and Congress. They were especially critical of punitive damages and class-action lawsuits, the legal process by which individuals band together as a group to sue over a common issue. Throughout the 1990s, lawyers at Gibson Dunn and other large firms argued that class-action court rules were too favorable to consumers and encouraged spurious lawsuits. A potential turning point came in 1998, when all federal courts adopted a procedural rule change that made defending large class action suits easier for corporations accused of wrongdoing. Under the previous rule, once a judge certified a class during pre-trial proceedings, appealing that decision became extremely difficult until after a trial had ended. The effect was pronounced: After a class was certified, most companies settled rather than risk large trial expenses and punitive damages. Because few cases were tried and appealed, there was a dearth of Supreme Court rulings on class action litigation. The rule change adopted in 1998 permitted a company to lodge an immediate appeal on the issue of class certification. Shortly afterward, Boutrous, Olson and other Gibson Dunn partners began strategizing ways they could use the new rule to help corporate clients. The Wal-Mart case caught the attention of Boutrous in 2004, shortly after a federal judge in San Francisco certified the class of 1.5 million women, the largest class in American history. Before moving forward with an appeal, Wal-Mart, the top Fortune 500 company, began looking for a new firm to handle the case. Many attorneys who were interviewed hedged their analysis, but the Boutrous pitch was different, recalls Michael Bennett, Wal-Mart’s general counsel for litigation. “He told us there that in all probability the Supreme Court was looking for a case like this,” Bennett said. At that point, Bennett said, few companies had the resources to risk the appellate costs and potentially punitive penalties that come with forgoing a settlement for trial. “Wal-Mart happened to be a client with enough staying power.” The case took six years to wend its way through the liberal-leaning U.S. 9th Circuit Court of Appeals. Judges ruled against Wal-Mart three times, including a 6-5 full court opinion in 2010. As Wal-Mart prepared to file a petition to the high court, however, Boutrous advised Wal-Mart that the Supreme Court’s make-up had become more favorable during the appeals process, lawyers involved in the case said. The 2005 and 2006 appointments of Roberts and Alito strengthened the pro-business orientation of a court already shedding its 1970s-era reputation as consumer-friendly. The Wal-Mart appeal became the first Supreme Court case heard under the 1998 rule change. A few months after Boutrous made his oral argument before the court, Wal-Mart won. In a 5-4 ruling, the court determined that the class of 1.5 million was too large to prove a pattern of discrimination. Afterward, the opposing lawyer, Sellers, said the decision overturned four decades of class-action jurisprudence. The business community hailed the decision as one that would curtail specious suits. Gibson Dunn posted a letter to clients the day after the ruling. “This is an extremely important victory for all companies, large and small, and for their employees,” the letter said. During a legal seminar that fall, Gibson Dunn attorneys demonstrated the stakes involved by displaying a PowerPoint slide with the logos of corporations that supported Wal-Mart at the Supreme Court – FedEx, Bank of America, Microsoft, Cigna, Kimberly-Clark, Walgreens, Dole, DuPont, Tyson, General Electric, Pepsi and Del Monte. Last year, the firm scored two more Supreme Court class-action victories. One was on behalf of Comcast, which had been sued by cable subscribers in the Philadelphia region. The other was on behalf of Standard Fire Insurance, a subsidiary of Travelers, which had been sued by homeowners in Arkansas. In the months that followed, Gibson Dunn lawyers said, the firm was approached by potential clients – corporations seeking help with class actions or other possible Supreme Court cases. The new clients include Toyota, Yamaha and Wackenhut (now G4S Secure Solutions). The fallout from the decision in the Wal-Mart gender discrimination case, meanwhile, has created another source of revenue for the top firms: Because the high court ruled that a nationwide class of 1.5 million was too large, smaller groups of women began filing similar lawsuits across the country. Each new filing created more business for plaintiff's lawyers - and for Wal-Mart’s law firm, Gibson Dunn. (Reporting By John Shiffman, Janet Roberts and Joan Biskupic; Editing by Blake Morrison and Amy Stevens)