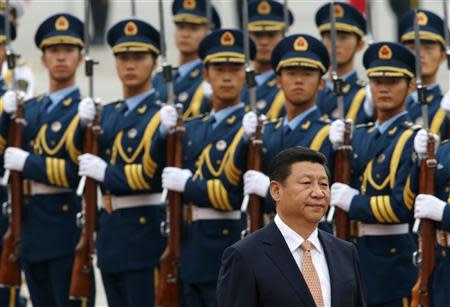

Special Report: Rising China's pride and challenge - its mighty army

(This story is part of a series, "Breakout: Inside China's military buildup") By David Lague and Charlie Zhu HONG KONG (Reuters) - It's part of the lore of modern China. When paramount leader Deng Xiaoping was handing over power a generation ago, a widely recounted tale goes, he had some advice for his successor. For every five working days, spend four with the top brass of the People's Liberation Army. The latest leader of China, Xi Jinping, shows every sign of applying that lesson. A month after assuming power in November last year, Xi visited the province of Guangdong on his first major political tour. Of the five days he spent there, three were at a military base, according to official coverage of his trip. The son of a Communist revolutionary commander, Xi built his career as a friend of the army, and at times an official in it. But he still feels compelled to ask his generals for something in return: loyalty. "First, we must keep in mind that the military must unswervingly adhere to the party's absolute leadership and obey the party's orders," he said on one of his many military inspection tours. Xi's injunction that the party comes first is a sign of the insecurity modern Chinese leaders feel at the top of their nation's huge and increasingly powerful armed forces, military experts say. As it grows mightier, the People's Liberation Army is growing trickier to govern. The PLA's rising global profile is integral to Xi's stated vision for the nation: the "China Dream," a rejuvenated country that's both peace-loving and militarily powerful. But Xi is less a true military man than Deng and the founder of the People's Republic, Mao Zedong. He is fundamentally a career bureaucrat, like his immediate predecessors, Hu Jintao and Jiang Zemin. Like them, Xi has to win over the force that keeps the Communist Party in power. But he must do so at a time when the PLA is more self-confident than ever, mounting the first serious challenge to the naval dominance of the United States since the end of the Cold War. "It will take time for Xi to take control of the military," says Huang Jing, an authority on the PLA at the National University of Singapore. "Most of the senior generals were not appointed by Xi. Instead they were all appointed by his predecessors." The rise of a nationalistic leader with military leanings comes as the People's Liberation Army, with 2.3 million men and women under arms, is the hard edge of a rising China. China's annual military spending is now second only to that of the U.S. armed forces. The PLA navy is projecting power further into the Pacific. Years of buying, copying and sometimes stealing technology have helped the PLA narrow its capability gap with the United States and other rivals in Asia. BEYOND BORDERS Xi, as chairman of the Central Military Commission, is commander-in-chief alongside his roles as party general secretary and president. He now oversees armed forces that are influencing events far beyond China's borders. Fleets of Chinese warships patrol disputed territories in Asian seas. On December 5, a Chinese warship forced a U.S. guided missile cruiser, the USS Cowpens, to take evasive action in the South China Sea, the U.S. Navy said. The incident, in international waters, appeared to be an attempt to prevent the U.S. ship from observing sea trials of China's new aircraft carrier, the Liaoning, naval experts said. PLA fighters now scramble to guard the controversial air defense zone that Beijing imposed last month off its east coast. The Chinese navy also cruises the Indian Ocean, contributing to international anti-piracy efforts, while PLA peacekeepers are on duty in Africa and the Middle East. In hardened silos and on mobile transporters, the PLA's Second Artillery Corps is modernizing China's modest but expanding armory of nuclear missiles, Chinese and foreign military analysts say. During Xi's tenure, likely to last another nine years, this force is expected to be bolstered with China's first effective ballistic-missile nuclear submarines. If PLA engineers can make them stealthy, these subs will be capable of retaliating if China comes under nuclear attack, according to Chinese and foreign military assessments. All this has been a dramatic change. In the late 1990s, visiting foreign military officers scoffed at China's poorly equipped army. After more than three decades of soaring military spending, infusions of foreign and domestic technology and improvements in training, the PLA is transformed. "There is no question China's power is growing," says Li Nan, an analyst of the Chinese military at the United States Naval War College. "That is contributing to a higher level of confidence." Reflecting the more complex military challenges China faces, Xi has moved to establish a national security commission, thought to be modeled on the U.S. National Security Council. No details about the proposed new body have been released. Foreign diplomats believe it is aimed at tightening coordination between China's sprawling military, intelligence, diplomatic and internal security agencies. Xi is likely to head the new body, according to several people familiar with the move. Xi is keeping his generals close. The military's top two commanders are almost always photographed at his elbow on his frequent visits to exercises, frontline units and military schools: army General Fan Changlong and air force General Xu Qiliang. He has also been quick to begin putting his own men at the top of the PLA hierarchy. Within days of taking over from Hu Jintao as head of the Central Military Commission in November last year, Xi promoted Wei Fenghe, commander of the Second Artillery Corps and member of the CMC, to full general. In late July and early August, he promoted six officers to the rank of four-star general, and 18 to lieutenant-general. Eleven of those 24 officers are political generals, said Bijoy Das, a Chinese expert at India's Institute of Defence Analysis. "In essence it indicates that the Party is co-opting a section of the PLA echelon to ensure that the 'Party holds the gun,'" he said. Xi is shown mixing with the lower ranks, too. Dressed in plain military-style khaki slacks and shirt, the solidly built 60-year-old stands in mess lines, selects a plate and chopsticks from a stack and is filmed eating and chatting with soldiers and sailors. MILITARY PRINCELING Xi, like all of China's Communist leaders, insists the PLA is bound with the party's fortunes. The army delivered political power with its civil war victory in 1949 over the Nationalists. It fought the U.S. to a prestige-enhancing stalemate in Korea. It buffered tumult at home in the early decades of the People's Republic and ended the 1989 Tiananmen protests in a bloody crackdown. In his task of cementing ties with the generals, Xi had a head start. His father, Xi Zhongxun, was a Communist guerrilla fighter who became a senior political leader and an architect of the market reforms that ignited China's economic boom. That makes Xi a "princeling" of the leadership, and he rubbed shoulders with other offspring of Communist China's founding elite. Throughout his career, Xi has appeared to march in step with the PLA. In his first job after graduating from Tsinghua University, he was a key aide in the general office of the Central Military Commission, the top military council he now runs. Xi was secretary to Geng Biao, a defense minister and former military subordinate of Xi's father. He held no rank, but his duties were considered military service. "The military sees Xi as one of their own," says a person with ties to the leadership. As he climbed the rungs of China's provincial bureaucracy, Xi had a parallel career as a political commissar in local army headquarters, units of the PLA and the People's Armed Police, the party's paramilitary internal security force. He was careful to defer to important old soldiers. About 10 years ago, when Xi was party chief in Zhejiang Province, a retired vice chairman of the Central Military Commission, Zhang Zhen, visited Zhejiang Province to celebrate his birthday. Xi, then provincial party chief, broke with his official duties for several days to accompany the civil war veteran. "Zhang Zhen was very touched with Xi's respect for old cadres," said the individual with leadership ties. "Those who came to offer their birthday felicitations all saw Xi next to Zhang. It was a plus for Xi." Zhang Zhen's own princeling son, general Zhang Haiyang, is now political commissar of the Second Artillery Force. As China has grown richer and better educated, the middle ranks of the PLA have filled with technically trained specialist officers. Along with that have come consistent if muted calls for China to have a fully professional army: one loyal to the state rather than the party, and free from the parallel supervision of political commissars who monitor the forces at virtually every level. Amid these rumblings, the army remains deeply politicized, military analysts say. The PLA has long-standing internal factions and loyalties divided between rival political benefactors and regional commands. While Xi was working his way up, Deng's successor, Jiang Zemin, was promoting dozens of senior officers who remain in positions of power today. Jiang was the man Deng advised to tend to the generals. In retirement, Jiang remains one of China's leading power brokers. His military appointments made sure his influence would outlast his term. Hu Jintao, who replaced Jiang, likewise sought to anchor his position through military promotions and patronage before handing over to Xi. Both Jiang and Hu kept the funding tap wide open for new military hardware and substantially improved pay and conditions for the troops. Xi appears set to maintain heavy military spending despite competing needs. A hundred million Chinese still live in poverty, according to official measures, and there is growing pressure to spend more on health, education and pollution control. Official defense spending is set to climb 10.7 per cent this year to $119 billion. Much spending takes place outside the budget, however, and many analysts estimate real outlays are closer to $200 billion, second only to the United States. The U.S. Defense Department's 2012 budget totaled $566 billion. FRIENDLY GENERALS As Xi came to power at the 18th Party Congress in November last year, there was substantial turnover in the Central Military Commission. Eight of 10 uniformed members of the council were replaced. It isn't clear if there is close patronage or loyalty between Xi and his top commanders. But other princelings, Chinese military analysts and foreign military attaches identify several generals with whom Xi is on especially good terms. One is Central Military Commission member Zhang Youxia. Also close are two officers outside that top body: army General Liu Yuan and air force General Liu Yazhou. (The two Lius are not related). Like Xi, these officers are princelings. Zhang Youxia is the son of General Zhang Zongxun, a celebrated senior commander in PLA's wars against the Japanese and the Nationalists. The elder Zhang fought civil war battles with Xi's father in north-western Shaanxi Province, according to people familiar with both men's family background. People close to the military say Xi last year wanted to nominate Zhang, now head of the PLA's General Armaments Department, as one of the two vice chairmen of the CMC. Retired leaders Jiang and Hu vetoed the move, these people say. Liu Yuan and Liu Yazhou are engaged in what they have described as an undeclared war by subversive foreign forces to unseat the Chinese Communist Party. They have also warned of the danger that unchecked corruption poses to the party's survival. Liu Yuan, 61, is the son of former president Liu Shaoqi, once designated to succeed Mao before he was brutally purged in the Cultural Revolution and died in custody. The elder Liu was posthumously rehabilitated after Mao's death, clearing the way for his son's life of privilege. In a late start to a military career, Liu Yuan joined the People's Armed Police as a political commissar at 41 before transferring to the army. He is now commissar of the PLA's General Logistics Department. Xi has publicly acknowledged his friendship with Liu on a number of occasions. Liu Yuan was also close to the powerful regional party chief Bo Xilai. Bo was sentenced to life imprisonment in September for bribery, embezzlement and abuse of power. Liu first attracted wide attention for a rambling essay he wrote as a preface for a friend's book in 2010. He called for China to reject imported political models, including Western democracy, and extremes of the left and right. In convoluted language, Liu nevertheless appeared to be suggesting a more open political system that would allow more robust debate without challenging the leadership of the party. More recently, Liu has led a rhetorical assault on corruption in the military. "Liu Yuan himself has become the anti-corruption poster child," says Huang from the National University of Singapore. The campaign mirrors Xi Jinping's declared attack on graft, in which he has threatened to go after "tigers and flies" - corrupt officials big and small. Liu Yuan helped bring down Lieutenant General Gu Junshan, who was sacked last year as deputy director of the PLA's logistics department and is soon expected to be court-martialed for corruption, according to three sources in Beijing. In an online discussion on the official People's Daily website on August 1, the military confirmed Gu was under investigation. Liu Yuan may have paid a price for his zeal. "He was passed over for promotion because of this, and also because he was too close to Bo Xilai," said a person with ties to the leadership who is familiar with the anti-corruption drive. "SILENT CONTEST" General Liu Yazhou, also 61, is the son-in-law of Li Xiannian, who became president in the Deng era. Liu Yazhou, too, is a political officer rather than a military professional. One of the most outspoken senior officers, Liu became well known as a writer of fiction early in his career. He later turned to politics and strategy, writing frequently about the decisive role that air power plays in modern warfare. For a time, he was widely regarded as one of the most liberal PLA officers. He once dared suggest that China needed a democratic political system to stamp out corruption and provide an environment where the best talent could get to the top. China routinely persecutes dissidents for airing similar views. His articles indicate he is an avid analyst of the U.S. military and the Pentagon's strategic thinking. More recently, however, Liu has written about the party's "absolute leadership" over the PLA. He also appears to have hardened his views on America. In his current posting as political commissar of the National Defense University in Beijing, Liu this year co-produced a documentary film, "Silent Contest." The documentary, thought to have been prepared for an internal military audience, appeared on Chinese websites for a couple of days in late October before being removed. The film warned of an American "soft war" against China aimed at toppling the party. "They confidently believe it would be easier to divide or split China by approaching and engaging China and integrating it into the U.S.-led international political system," Liu says in the film. The documentary includes similar warnings from other uniformed senior officers. And to clinch the message, General Liu rolls out his heaviest weapon: the commander-in-chief of the PLA and leader of the Communist Party. "Western countries' strategic goal of containing China will never change," Xi Jinping is quoted as saying. "They absolutely don't aspire to see a big socialist country like us achieve peaceful development." (Reporting By David Lague and Charlie Zhu in Hong Kong and Benjamin Kang Lim in Beijing. Edited by Bill Tarrant and Michael Williams.)