The Supreme Court goes for a civil rights hat trick

Amid the swirl of excitement following the Supreme Court’s decision to consider the issue of same-sex marriage, you may have missed news of a housing discrimination case that could have huge implications for civil rights.

But first, a little history.

Among the many achievements of the American civil rights movement, three pieces of legislation stand above all others: the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Voting Rights Act of 1965, and the Fair Housing Act of 1968. President Lyndon B. Johnson and his allies, both in and out of government, established these important tools to combat the historical effects of slavery and discrimination.

In the last decade, however, the Supreme Court has accelerated a rollback of these regulations in a series of controversial decisions. The Court halted school integration in Parents Involved in Community Schools v. Seattle School District No. 1 (2007) and limited employment protections in Ricci v. DeStefano (2009). More recently, it undercut voting rights in Shelby County v. Holder (2013) and weakened affirmative action in Schuette v. Coalition to Defend Affirmative Action (2014).

And now, the Court is poised to act again after hearing oral arguments on Wednesday in Texas Department of Housing and Community Affairs v. The Inclusive Communities Project.

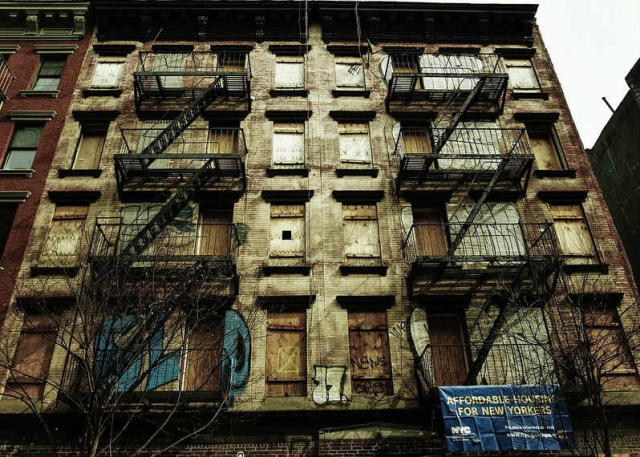

The case began in 2008, when the Inclusive Communities Project filed a lawsuit against the Texas state agency for the distribution of tax credits in a way that reinforces and increases racial segregation. Because landlords who receive the tax credits are required to accept affordable-housing vouchers from low-income tenants—many of whom come from minority communities—the allocation of those credits has an outsized impact on racial housing patterns.

Courts at the district and circuit levels agreed with the ICP, concluding that Texas’ distribution of tax credits violated the FHA because of its “disparate impact” on minorities. Critical to those rulings, and to the current fight at the Supreme Court, is an understanding that disparate impact requires evidence not of intentional discrimination, but merely of harmful effects.

In fact, that understanding of the law—one resting on impact, not intent—has been upheld by all 11 federal circuit courts. The ICP, supported by the federal government, also argues that this understanding is in concert with Congress’ original intent in passing the law, seeking to combat both intentional discrimination and the subtle, hidden practices that reach the same result.

On the other hand, Texas points to the text of the FHA, which says it is illegal to “refuse to sell or rent … or to refuse to negotiate for the sale or rental of, or otherwise make unavailable or deny, a dwelling to any person because of race” [emphasis added]. The plain text suggests the law is limited to explicit acts of discrimination and nothing more.

During oral arguments, however, the state found an unlikely opponent in Justice Antonin Scalia.

“The law consists not just of what Congress did in 1968, but also what it did in ’88,” he said, referring to later amendments to the FHA. “And you look at the whole law … and if you read those two provisions together, it seems to be an acknowledgment that there is such a thing as disparate impact.”

In essence, Justice Scalia argued that the fact that Congress wrote in FHA exemptions to disparate-impact claims in the 1988 amendments is evidence that Congress affirmed the legitimacy of such claims.

“Why doesn’t that kill your case?” he asked.

Later, however, Justice Scalia echoed traditional conservative aversion to race-conscious government policy by suggesting that disparate-impact claims require race-conscious analyses and remedies.

“Racial disparity is not racial discrimination,” he said. “The fact that the NFL … is largely black players is not discrimination. Discrimination requires intentionally excluding people of a certain race.”

Other Justices played familiar roles.

“This has been the law of the United States uniformly throughout the United States for 35 years, it is important, and all the horribles that are painted don’t seem to have happened, or at least we have survived them,” said Justice Stephen Breyer of the FHA. “So why should this court suddenly come in and reverse an important law which seems to have worked out in a way that is helpful to many people, [and] has not produced disaster?”

“Is there a way to avoid a disparate-impact consequence without taking race into account in carrying out the governmental activity?” countered Chief Justice John Roberts. “It seems to me that if the objection is that there aren’t a sufficient number of minorities in a particular project, you have to look at the race until you get whatever you regard as the right target.”

Given the Supreme Court has tried twice before to rule on cases like this one, despite a lack of doctrinal disagreement among the lower courts, supporters of disparate-impact theory have little reason to be optimistic about the outcome.

Still, one never knows how the Court will ultimately shake out. Maybe the third time will be the charm that stops the charge.

Nicandro Iannacci is a web strategist at the National Constitution Center.

Recent Stories on Constitution Daily

Podcast: Should elected judges be allowed to ask for donations?

Constitution Check: Do court decisions in favor of civil rights create real rights?