Surprise! Life Discovered Inside Deep-Sea Rocks

Towering rocks at the bottom of the ocean hold a surprising secret: Life.

These rocks, near natural methane seeps on the seafloor, are home to methane-munching microbes, new research finds. What's more, it appears these tiny rock-dwellers may chow down on enough methane to effect global levels of the gas, which can contribute to climate change.

"We've recognized for awhile that the deep ocean is a sink for methane, but primarily it has been thought that it was only in the sediment," said study researcher Jeffrey Marlow, a graduate student at Caltech. "The fact that it appears to be active in the rocks itself sort of redistributes where that methane is going." [Gallery: Amazing Images of Atlantic Methane Seeps]

Methane and microbes

About 15 years ago, Caltech geobiologist Victoria Orphan and her colleagues discovered that the mud on the seafloor near methane seeps is anything but dead dirt. Instead, it's full of microbes — bacteria and nucleus-free organisms called archaea — that eat the natural methane bubbling up from subsurface reservoirs. Between 6 and 22 percent of the world's methane (a greenhouse gas) is released through these seeps, or cracks in the ocean floor, said Marlow, who is one of Orphan's students. Microbes eat about 80 to 90 percent of that.

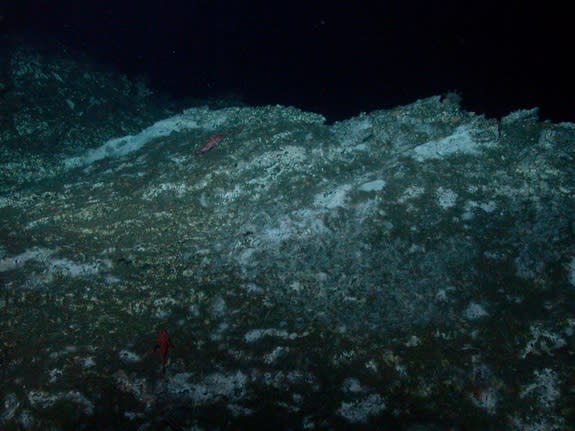

Dominating the landscape at these sites, however, are enormous rocks, hundreds of feet tall and hundreds of feet long. The rocks are carbonates, meaning they are made of minerals from the surrounding seawater. No one had ever studied these rocks to see if they, like the seafloor mud, hosted life, Marlow said. [See Photos of Weird Deep-Sea Life]

The researchers launched two expeditions to the deep at a place called Hydrate Ridge 62 miles (100 kilometers) off the coast of Oregon. This undersea formation is dotted with methane vents. There, in the near-freezing waters 2,625 feet (800 meters) down, the scientists took samples of rock near active methane seeps as well as from spots without methane activity. One expedition used Alvin, a manned research submersible operated by the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI). The other used the remotely operated submersible Jason, also run by the WHOI.

Rock-dwelling life

Jason and Alvin returned 24 rock samples, which the researchers studied alongside samples from other methane seep areas in the Eel River Basin off northwestern California and the Costa Rica margin off Costa Rica. Using microscopes, they saw that rocks adjacent to the methane seeps were full of clusters of microbes. DNA analysis revealed both bacteria and archaea in similar ratios as seen in the seafloor mud.

But what were these microbes doing? To find out, the researchers attached certain molecules to methane that they then exposed to the rock-dwelling microbes. These molecules acted as tracking devices, allowing the researchers to see where the methane and its components ended up.

The tracking studies revealed that the methane ended up in the bellies of the microbial beasties discovered inside the rocks — and then in the rocks themselves. It appears that the microbes process the methane and excrete byproducts that mineralize around them, forming the towering rocks in a process of "gradual self-entombment," the researchers report today (Oct. 14) in the journal Nature Communications.

"We think that the microbes are processing the methane into bicarbonate, and then that bicarbonate links up with calcium in the seawater to make calcium carbonate," Marlow explained.

Granted, entombing oneself in rock doesn't seem like the best bet for survival, Marlow said. But it's likely that the microbes still get their methane supply through pores or fissures in the rock. Researchers only sampled from the first few inches of rock, so they aren't sure how deep the microbial communities penetrate below the surface.

Like carbon dioxide, methane is a greenhouse gas, capable of trapping heat from the sun in the Earth's atmosphere. Though carbon dioxide is more abundant and thus contributes a greater proportion of global warming, methane is actually about 30 times as potent as CO2 at trapping heat. Marlow, Orphan and their colleagues aren't yet sure how much of the microbial methane-munching activity happens in rocks versus in seafloor mud, but the rock-dwellers "might be a very strong contributor," Marlow said.

What's more, the methane-eating microbes are likely the basis of an alien ecosystem on the seafloor, playing the same role that plants play on land.

"There are worms crawling in and around in the rocks, in the sediments, that are very likely eating these clumps of cells," Marlow said. "So they really are the primary producers in this entire system."

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Copyright 2014 LiveScience, a TechMediaNetwork company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.