The technology that may finally make ‘clean’ cookstoves a reality

Billions of people around the world still cook inside over open fires. They burn dung, wood and charcoal to fuel the flames, clouding their homes with toxic fumes.

For activists and entrepreneurs, this has seemed like an easy fix: Design a cleaner cookstove, get it in the hands of the people who need them, and harmful emissions of "black carbon," or soot, that damages people's lungs and contributes to climate change will decline.

In recent years, millions of impoverished families have received clean cookstoves via public and private initiatives. Yet black carbon is still a major health problem, in part because families can't afford to fix the clean cookstoves when they break.

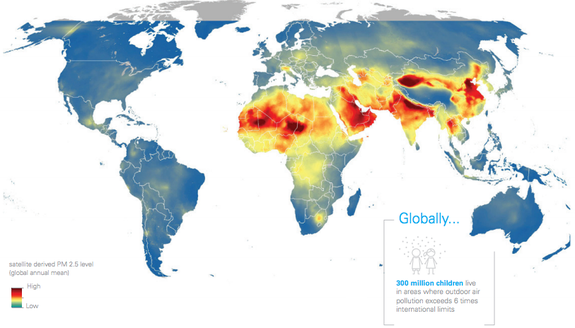

SEE ALSO: 2 billion children are breathing toxic air, UNICEF reports

Now a team of scientists in California might have found a way to crack the cookstove code.

Using wireless data technology and cell phone networks, the group designed a system that enables women in rural India to use and repair cleaner stoves and be compensated for doing so.

Image: anupam nath/AP

They published the results of their two-year pilot project in the Oct. 31 online edition of Nature Climate Change.

"We're looking to empower women to not only be able to afford the stoves, but afford to keep the stoves running," said Nithya Ramanathan, a senior researcher for Project Surya, which led the initiative.

The team is planning to grow the project from 4,000 homes in rural India to a million households within the same region. At that scale, "a literal cloud of air pollution would disappear," Ramanathan told Mashable.

Black carbon is made of tiny particles that come from burning solid biomass such as dung and wood. When regularly inhaled, it can cause lung cancer, heart disease and other illnesses.

Image: UNICEF

The World Health Organization estimates around 4.3 million people die prematurely each year from illnesses linked to household air pollution.

Public health experts who weren't involved with the experiment said they were excited by the initial field results and the potential to use wireless technologies to spur greater use of clean cookstoves.

"It is time the rural development world fully embraced modern IT techniques such as these," Kirk Smith, a professor of rural environmental health at University of California, Berkeley, said by email from India.

The experiment

Because not all cookstove designs are created equal, Project Surya limited its pilot project to a certain type of "forced-draft" stove. The $70 model still burns cheap biomass, but it uses fans to lower fuel use, shorten cooking times and limit harmful smoke.

Image: bebeto matthews/AP

Starting in May 2014, the team worked with 4,038 households in the eastern Indian state of Odisha.

Nexleaf Analytics, Ramanathan's non-profit tech company, developed a wireless sensing system to monitor the families' use of the cookstoves. About 450 homes had the wireless sensors, while the remaining households manually logged their usage.

The team found that one hour of cooking on the clean stove reduced air pollution by about 0.003 tons of carbon dioxide equivalent. Women could earn $6 for each avoided ton, or about $32 a year if they used the stove for five hours every day.

That's a sizable chunk of change for families who typically earn just $2 a day. But it wasn't enough to push women to go out, buy extra fuel and run their stoves longer than needed to rack up extra credits, Ramanathan said.

Image: AP photo/anupam nath

The 17-month experiment encountered a few hitches.

Within the first six months, about half of the stoves broke down, and only half of the duds were repaired. Women in isolated villages also had trouble collecting their cash payments.

Through trial and error, Project Surya found the best way to pay women was to send credits via cell phones through M-Pesa, a money transfer service similar to PayPal. Local agents cashed out the credits at banks in town and then traveled to villages to hand women the cash.

Researchers are now working to build local repair networks, said Tara Ramanathan, Nithya's sister and a program director at Nexleaf.

Their father, Veerabhadran Ramanathan, heads Project Surya and is a prominent climate scientist at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in San Diego.

Scaling up

Women in Project Surya's pilot project earned about $70,000 in total carbon credits. With a million participants, payments would likely total about $100 million a year.

The funding could come from governments and financial institutions in developed countries, which have pledged to invest $100 billion a year to finance climate change projects in developing economies, Nithya Ramathan said.

Image: Akram Saleh /Getty Images

But public health experts said Project Surya's initiative has several kinks to iron out if it's going to scale to millions of households.

Smith, the Berkeley professor, said the team should also attach wireless sensors to the conventional, polluting stoves. In his own research in northern India, Smith found that families continued to use their traditional stoves even with a cleaner model in the house — a process known as "stacking" that undermines the health benefits of new, cleaner stoves.

Rema Hanna, a Harvard University economist who led an extensive field study on clean cookstoves in 2012, said that while she applauded Project Surya's work, further research is needed to see if this model can actually curb indoor air pollution or financially motivate families at a larger scale.

"Before we start scaling up financial incentives, I would encourage even more testing of this model in other settings," she told Mashable.

Hanna said that in general she believes researchers should postpone initiatives to deliver clean cookstoves to rural communities, given how many stoves end up broken or unused.

"Researchers should focus on both improving stoves and testing other potential solutions before we spend lots of money and resources doing large-scale stove interventions," she said.