The tragic final night of Jose Fernandez's life

MIAMI – A few minutes before midnight, Will Bernal’s phone buzzed. Up popped a text message from one of his best friends, Eddy Rivero. They had spent a lot of time together the previous week after another close friend of Bernal’s was killed. Now Rivero needed help. This was really important. Rivero asked to talk.

Bernal stepped outside and took the call. Rivero’s friend, Jose Fernandez, had asked him to go for a late-night ride on a 32-foot fishing boat into the wee hours of Sunday. This sounded bad. Bernal had ridden on a boat at night once, and it was terrifying. Not just the darkness, but the choppy waves from the rain earlier in the day and the threat of other boats and the objects obscured by the night.

“I told him it was a horrible idea,” Bernal said. “Do everything you can to get him off the boat. Do whatever you can to get him on land.”

Fernandez, the Miami Marlins’ star pitcher, was upset and just wanted to get away, Rivero told him. He loved boating. He wasn’t going to budge. Bernal tried to reason with Rivero. Bernal had lost one friend already. He didn’t want to bury another. Surely Fernandez’s gloom, Bernal said, had to be fleeting. “Both of you guys have a bright future,” Bernal said. “Whatever he’s stressed out about today he won’t remember a week from now.”

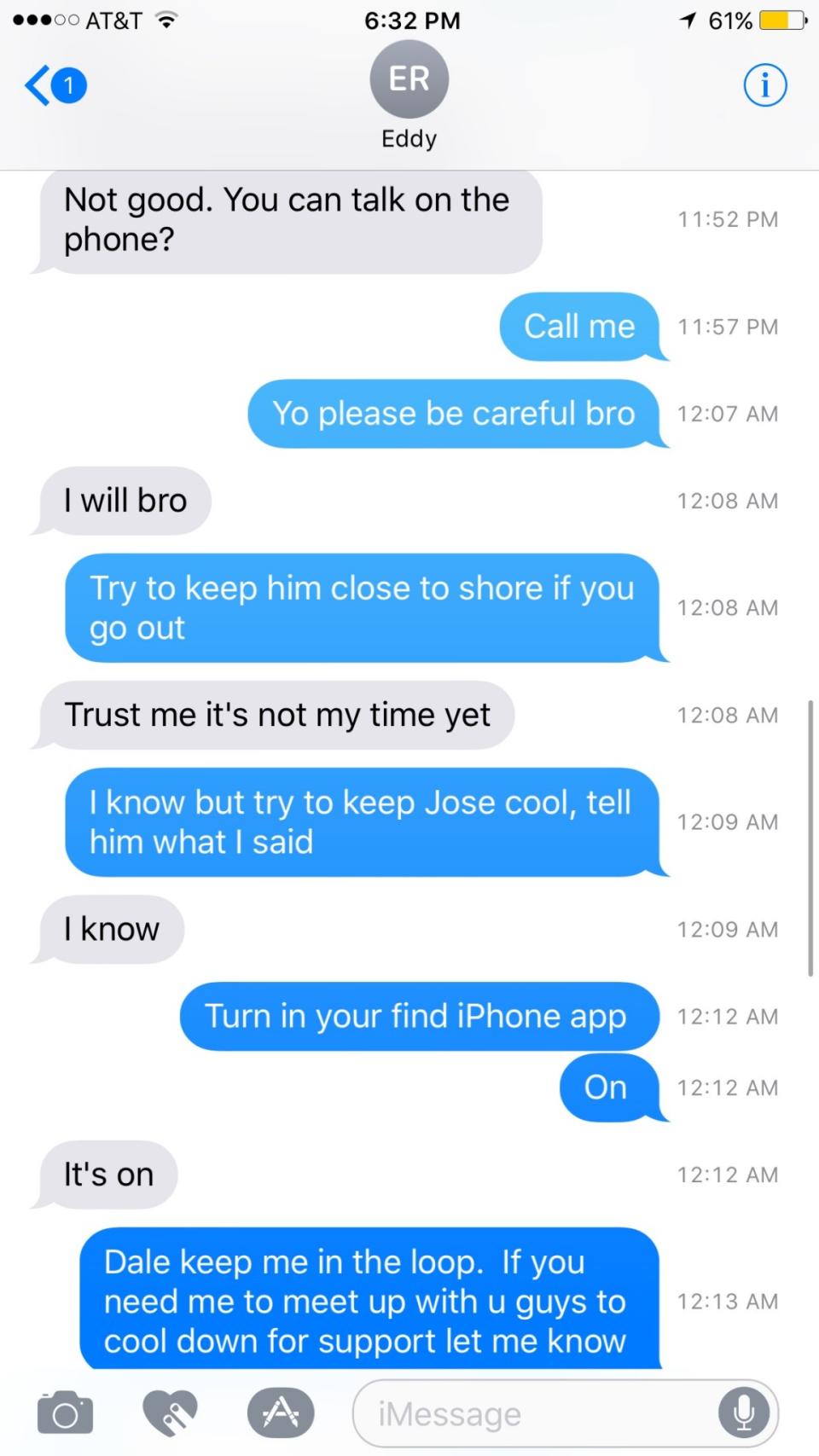

After Bernal said goodbye, he picked up his phone and shot Rivero a message.

“Yo please be careful bro,” Bernal texted at 12:07 a.m.

“I will bro,” Rivero said.

“Try to keep him close to shore if you go out,” Bernal wrote a minute later.

“Trust me,” Rivero wrote, “it’s not my time yet.”

Rivero was young, 25 years old. He’d met Fernandez through his girlfriend, who was friends with Fernandez’s. He’d started working at Carnival Cruise Lines and was trying to save up money to pay off his debt and buy an engagement ring.

Fernandez’s girlfriend was pregnant, and even if they were in different economic stratospheres, there was a kinship there between two Cuban sons who loved their family and friends and good times and Miami. So when the 24-year-old Fernandez insisted on going out, Rivero couldn’t say no. He trusted he would return safely.

“I know,” Bernal said, “but try to keep Jose cool, tell him what I said.”

“I know,” Rivero replied.

“Turn in your find iPhone app,” Bernal said, correcting himself to say “on.”

“It’s on,” Rivero wrote.”

“Dale [go ahead] keep me in the loop,” Bernal said. “If you guys need me to meet up with u guys to cool down for support let me know”

At 12:13 a.m., the texting stopped, and Bernal said he started to track the boat, nervous the dot would stop moving. Around 2 a.m., it did, at American Social Restaurant and Bar, a gastropub along the Miami River. Above the restaurant is the Neo Vertika condominium building, where 27-year-old Emilio Macias, a friend of Rivero’s who never had met Fernandez, lived. Bernal checked in with Rivero. They were docking the boat, waiting for Macias. Rivero said everything was cool. Around 3 a.m., Bernal stopped tracking the boat on the iPhone app and fell asleep. He had a soccer game a few hours later. He needed some rest.

Bernal slept late and hustled to the game without checking his phone. After the hour-long game, he saw a text message. Fernandez had died when the boat struck a rocky jetty and flipped. The other two passengers on board had died.

“I just had this horrible feeling,” Bernal said. “I knew. I knew.”

He still hoped this was all a mistake, a terrible, awful nightmare. Bernal called Rivero. There was no ring. It kicked straight to voicemail.

***

The grief around baseball Sunday evolved into something worse Monday. The despair felt crippling, the shock palpable. It was real. Three young men were dead, and one of them was Jose Fernandez, the smiling, dancing right-handed pitcher who imbued baseball with something different. He was alive, in every sense of the word. And now he wasn’t.

Outside Marlins Park, fans set up a memorial and signed a wall and embraced one another because the shared experience of witnessing Fernandez was that visceral. He was everything baseball should be: joyous and free and fun. Inside the stadium, they tried to honor that and soldier through their pain.

Coach Arnie Beyeler hit fungoes to infielders and Giancarlo Stanton launched balls from the batting cage and Dee Gordon stood at second base, fielding ground balls. In a sea of black Marlins jerseys, Gordon wore white. He had a T-shirt made. It said RIP. The R and P were big, block letters. A cutout photo of Fernandez represented the I.

Dee Gordon paying tribute to Jose Fernandez with custom T-shirt and "JDF16 4EVER" on his cap. (photo via AP) pic.twitter.com/mxPj2fzF9I

— Big League Stew (@bigleaguestew) September 26, 2016

Normally during batting practice, he would be flitting around, chirp-chirp-chirping in one teammate’s ear and then bebopping to another. He was a gnat. And they loved him anyway. When everyone gathered inside the clubhouse for a pre-BP meeting Monday – players and coaches and the front office and ownership and even the team chef – they cried. They cried not just because he was gone, but because he was fundamentally good. He escaped Cuba as a 15-year-old after three failed attempts. He made something of himself, of this new life. He worked on behalf of ridding childhood cancer. He carved out time for kids, always, because he was just a kid himself, in heart and deed.

It made Sunday that much more regrettable. He could’ve done a million other things. After Saturday’s game, Fernandez had asked a number of teammates to join him on the boat. One by one, they declined. And there they were Monday, back in uniform, the uniform he was supposed to be wearing, too, thinking that if not for the instinct that told them to say no, it could’ve been them.

No. They couldn’t think like that. They wouldn’t allow themselves. This was too much already. They were all wearing Fernandez’s No. 16 jersey, which the Marlins would retire after the game. They were trying to wipe away the tears during a gorgeous trumpet version of “Take Me Out to the Ballgame” that came before the “Star-Spangled Banner,” sung note-perfect by a choir of children. After the anthem, New York Mets players gravitated toward the Marlins, and the teams exchanged hugs. The Marlins then encircled the pitcher’s mound, drew messages in the dirt, picked up a handful and dirtied up their pant legs. They huddled behind the mound and pointed to the sky. They wanted to believe he was laughing.

That was Fernandez’s default. The stories everyone traded Monday were classic. Like the time one person met Fernandez at the All-Star Futures Game in 2012. He was a burgeoning prodigy, a $2 million bonus baby who a year later would be starting in the major leagues for the Marlins. At that point, Fernandez’s ego was the thing of legends, outsized to the point of hilarity. When Fernandez was told a couple other pitchers hit 100 mph with their fastballs and he touched only 99, his response was: “I’m not feeling that great. A little sore throat, so I took it easy.”

Later that year, he was practicing in the offseason at Alonso High in Tampa, from which he graduated after he defected. A Tampa Bay Rays executive happened to be scouting another player there, and he ran into Fernandez, who said he had been thinking about it, and he’d love to play the last five years of his career for the attendance-allergic Rays. “I can put asses in seats,” Fernandez said. He was 20. He hadn’t thrown a single major league pitch.

The executive thought to himself: Who the hell does this kid think he is? Jose Fernandez. That’s who. He willed people to love him, and when they started to understand the enormity of his personality, they couldn’t help themselves. Fernandez was like a brother to Dee Gordon, which is why when he stepped to the plate to lead off the bottom of the first inning Monday, Gordon, a left-handed hitter, stood in the right-handed batter’s box like Fernandez and took one pitch.

Gordon shifted to the other side and stared at another. Then Mets pitcher Bartolo Colon left an 85-mph fastball over the heart of the plate, and Dee Gordon, who had not hit a home run in 323 plate appearances this season, and hit just eight in his six-year career, hammered a ball 377 feet over the right-field fence. As he rounded the bases, tears welled in his eyes. When Gordon crossed home plate, he wept uncontrollably.

***

Around Miami, they cried Monday, too. Jose Fernandez was this city, with his Cuban blood and his joie de vivre and his love of the water. That part hurt. The ocean that gave him freedom took his life. He spent as much time as he could on the water, with his friend Jessie Garcia, who brought Fernandez on sport-fishing expeditions all over.

Sometimes they went to Cat Cay in the Bahamas, about 50 miles from Miami. Jonathan Dames, the Cat Cay dock master, said Fernandez and Garcia would go on late-night trips, coming back at 10 or 11 at night, because swordfish bit best in the dark.

“Swordfish is one of the sweetest fish inside the sea,” Dames said. “That’s why they’d always go for it. That was Jose’s favorite meal.”

Sometimes Fernandez would go to Cat Cay on his off-days. He would have lunch and play basketball and look at the chickens and iguanas on the island. He was ever curious, wanting to learn more about fishing and to drive the boat.

“Jessie kept telling him no,” Dames said. “I think Jessie knew he wasn’t ready to start going out on his own. Jessie always controlled the vessel. He made sure everybody got back safe. He wasn’t allowing [Fernandez] to buy a vessel at the time.”

It remains unclear whether Fernandez was driving at the time of the accident. Bernal said Eddy Rivero did not have a boating license and had minimal experience driving a boat. Authorities said the boat, named “Kaught Looking” and tagged with a backward K and two baseballs for Os, accented in Marlins colors, was registered to Fernandez.

A photo posted by Jose Fernandez (@jofez16) on Jul 16, 2016 at 8:19pm PDT

The water tried to take Fernandez once before. On his fourth attempt at defection, his mother, Maritza, fell in the water. Fernandez jumped in and saved her. Their bond was unbreakable before. When he was 7 years old, she sewed him a pair of bright red baseball pants, just like his heroes on the Cuban national team. The two of them and Fernandez’s grandmother Olga, whom the Marlins helped bring to the United States from Cuba in 2013, were practically inseparable.

Sometimes, along with Fernandez’s girlfriend, they would go to the famous Versailles restaurant for a taste of home. They always sat at the same table: No. 91, in the back left-hand corner of the restaurant, with its banquet chairs and hexagonal tile floor and old-school feel and smell of a place every native Cuban knows and adores.

The first time Fernandez came to the restaurant, its owner, Felipe Valls Jr., approached his table to say hi. “With all the famous people who came here,” Valls Jr. said, “it’s the first time someone has stood up to take a picture with me without me asking.” At Versailles, Fernandez turned down the volume. He was quiet and humble and said please and thank you. One time he ate black beans and rice and a big steak and hit a home run that night. Most of the time, he ordered The Criollo, a sampler platter.

“He loved The Criollo,” said Luis Camacho, who often bused table No. 91.

“Rice, beans, croquettes, pork – a little bit of everything,” said Leticia Cohen, who on occasion was Fernandez’s waitress.

Camacho is 22 years old. He left Cuba for Miami as a boy. He saw Fernandez as so many Cubans do: proof that it’s not just freedom that is abundant on America’s shores but opportunity. Fernandez arrived as an immigrant April 5, 2008, under the wet-foot, dry-foot policy that allows Cubans to stay, and almost seven years to the date he became a U.S. citizen.

“When I heard the news, I was sitting near my wife,” Camacho said. “I started to cry. She asked why, and I told her Jose Fernandez died. I called my aunt here. And she told me, ‘Don’t tell me nothing about it.’ ”

They didn’t want to hear because they refused to believe he was gone, that they’d never see that 100-mph fastball anymore. When Fernandez returned from Tommy John surgery and hit 100 for the first time, he took a screenshot of the radar gun from the TV broadcast, texted it to his surgeon, Dr. Neal ElAttrache, and captioned it: “There it is!” He never hogged his bliss. It was everyone’s to share in.

It’s why even on a Marlins team that struggles to draw and keep fans, Fernandez’s starts were events. The fastball. The ruthless curveball. The competitiveness. All of it felt unique, appointment viewing.

“He was supposed to pitch today,” Cohen said.

He was, though originally Fernandez’s start was slated for Sunday. The Marlins bumped him back a day. Had they kept him on schedule, he never would’ve gone out Saturday night.

***Last Tuesday, Will Bernal and Eddy Rivero decided to go to a Marlins game. Bernal was despondent over the death of a friend, and Rivero helped score tickets to watch Jose Fernandez pitch. They sat next to his girlfriend.

“We just talked about life,” Bernal said, about how short it was and how much he and Rivero were looking forward to a trip together to Las Vegas in October. Bernal went home that night appreciating Rivero even more. They were fellow sneakerheads who met because of their shoe-collecting hobby, and they’d grown into true friends. Rivero couldn’t thank Bernal enough for gifting him a pair of red Air Jordan 1s recently for the same he reason he didn’t say no to Jose Fernandez early Sunday: He wanted to give more than he took.

“Eddy was always the type of guy who would put others before him,” Bernal said. “He was a genuinely nice, caring person. The type of human you want to meet and have as a friend. It’s so hard to find friends like that.

“He lost his life being a good friend.”

Guilt consumed Bernal on Monday. He wanted to run out of his house and yell at Rivero and Fernandez to get off the boat, to be smarter, to save themselves. He didn’t want the last memories of Rivero to be the text messages and the conversation about how much Rivero loved his little niece and the Marlins game they attended together. He didn’t want his final piece of Fernandez – “A stand-up guy,” Bernal said, “very humble and likeable, especially for a pro athlete” – to be watching him on the mound.

Of course, if there was a Fernandez game to witness, this was it. Fernandez hadn’t pitched that well in more than two years, before his elbow blew out. This was a masterpiece. Eight innings. Three hits. No runs. No walks. Twelve strikeouts. The Washington Nationals, champions of the National League East, had no answers.

Bernal and Rivero marveled at Fernandez, congratulated his girlfriend, went off into the Miami night looking forward to so many more like this. Bernal is 32, and on occasion he tried to warn Rivero that they weren’t invincible, that they should savor what they had. It’s why the text message saying it’s not Rivero’s time to go so haunts Bernal, and why the ink on one of Rivero’s arms gives him goosebumps just the same.

“Life is Short,” the tattoo said. “Heaven is Forever.”

(A GoFundMe was started in memory of Eddy Rivero.)