The top 10 presidential power plays of all time

As Constitution Daily explores the debate over the power of the executive, here’s a look at the controversial president power moves that are usually mentioned in Imperial Presidency discussion.

The Founders were deeply concerned about a President so powerful that he or she would rival the monarchs of Europe.

In modern times, the historian Arthur Schlesinger Jr. framed the Imperial Presidency or Unitary Executive theory as driven by events “so spacious and peremptory as to imply a radical transformation of the traditional polity.”

Or in other words, the events were acts by a President that upset the balance of power greatly among the executive, legislative and judicial branches, he argued.

“My argument … [is] that the American Constitution intends a strong presidency within an equally strong system of accountability,” Schlesinger said. The idea of the Imperial Presidency, he said, “referred to what happens when the constitutional balance between presidential power and presidential accountability is upset in favor of presidential power.”

Here are some historical events noted by Schlesinger and others that can be considered presidential “power grabs” or legitimate acts of powers, depending on your viewpoint.

John Adams: The Alien and Sedition Acts

In 1798, as the United States, and its Federalist Party-controlled government, considered war against France, Adams led the drive to pass four acts that curtailed constitutional rights. More than 20 Republican newspaper editors were charged under the act, and one House representatives was jailed for criticizing Adams.

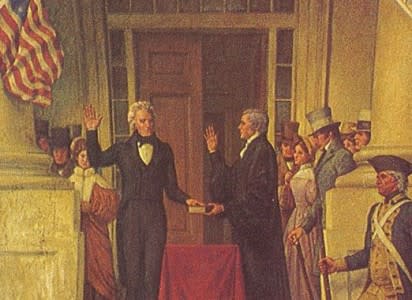

Andrew Jackson: The President ignores the Supreme Court

The controversial general-turned-president practiced the art of nonacquiescence, or the act of totally ignoring another branch of the government. In Jackson’s case, this was the Supreme Court. In 1832, the Court ruled that Georgia didn’t have the right to evict American Indians from the state. Jackson’s reported response was, “John Marshall has made his decision, now let him enforce it.” Other accounts indicate Jackson’s comments were less colorful but had the same effect.

John Tyler: The VP declares himself as President

When President William Henry Harrison died in 1841, after just one month in office, the nation faced a true constitutional crisis. The founding document was vague about what happened next: Was the vice president just acting as president until a new special election was called? Or was his title president, acting president or vice president? Tyler boldly assumed power as the legitimate president for the next four years; his action set the Tyler Precedent for presidential succession, but it wasn’t legalized until the 25th Amendment was adopted in 1967.

Abraham Lincoln: Habeas Corpus suspended

During the Civil War, President Lincoln told the bold step of suspending the writ of habeas corpus several times – the most basic of fundamental constitutional rights. At one point, Chief Justice Roger Taney issued a ruling that Lincoln didn’t have the power to suspend habeas corpus. Lincoln ignored Taney.

Woodrow Wilson: The Palmer Acts

The former political science professor echoed John Adams when he advocated for another Sedition Act (along with a Naturalization Act) during World War I. Known as the Palmer Acts (after Wilson’s attorney general), the laws made it a crime to protest against the war or criticize certain government actions. Eugene V. Debs, the labor leader, was sentenced to 10 years in prison for making an anti-war speech.

Franklin Roosevelt: Packing the Supreme Court

The second President Roosevelt took up an unusual tactic to get around Supreme Court justices who opposed some of his New Deal efforts: He wanted to add more justices to the Court to get a favorable majority. After hitting political resistance in Congress, the court packing plan went by the wayside after the Court issued a favorable ruling on a New Deal case.

Franklin Roosevelt: Executive orders and Korematsu

Roosevelt’s executive order 9066 authorized the internment of tens of thousands of Japanese-American citizens and resident aliens from Japan in the western part of the United States during World War II. The Korematsu decision in the Supreme Court upheld the executive order, saying that that the need to protect against espionage outweighed Korematsu’s constitutional rights as a citizen. The order and the Supreme Court decision remain controversial today.

Harry Truman: Seizing the Steel Mills

In April 1952, President Harry Truman seized control of steel industry during a labor dispute during the Korean War. Truman issued an executive order allowing the federal government to seize steel mills and run the industry. The move was immediately unpopular and Truman received the ultimate rebuke: The Supreme Court found the act unconstitutional. Unlike Jackson and Lincoln, Truman obeyed the Supreme Court order, and after a 53-day strike, Truman helped to mediate a settlement.

George H.W. Bush and Barack Obama: Warrantless wiretaps

In two separate cases, presidents from different parties justified the warrantless wiretapping of Americans’ phone records (and in some cases, electronic communications) under of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (or FISA).

The legal justification for the actions came in the aftermath of the 9/11 terrorist attacks. President Bush’s executive order allowed the National Security Agency to conduct warrantless surveillance on specified telephone calls. The FISA Amendments Act of 2008 and a reauthorization act in 2012 ensured the program would continue through the Obama administration, which has strongly defended its legality. But at some point, the issue is expected to arrive at the Supreme Court.

Recent Constitution Daily Historical Stories

10 WPA posters that remain fascinating today

An early President’s great leap of faith

The day that Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. died

Controversial trailblazer: Remembering the first woman in Congress