Town of Greece v. Galloway: Legislative prayer sessions and the Establishment Clause

Alexander Fullman previews Town of Greece v. Galloway, a big case in front of the Supreme Court on Wednesday that involves prayers at public meetings and the First Amendment.

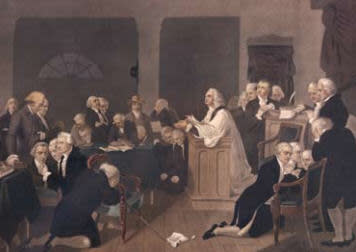

Prayer at the Continental Congress, 1774

In 1999, the town of Greece — population 94,000 — in the state of New York instituted the practice of beginning its town meetings with a religious prayer, delivered almost exclusively by Christian clergy selected by a town employee from a list lacking non-Christian faiths.

Two residents in the town, Susan Galloway and Linda Stephens, objected to these prayers offered at the start of the local town board sessions. In response to a lawsuit, the town modified its practices, and a member of a Baha’i congregation, a Jewish man, and a Wiccan priestess delivered invocations. Yet, because the overwhelming majority of clergy belonged to Christian denominations, who often referenced Jesus Christ and invited those present to join in prayer, Galloway and Stephens felt that the prayer sessions violated the First Amendment’s Establishment Clause, which says that “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion.” The case made its way to the Second Circuit Court of Appeals, which sided with Galloway and Stephens in holding that the heavy Christian influence of the prayers unconstitutionally violated the Establishment Clause.

When the Supreme Court hears oral argument in the appeal of Town of Greece v. Galloway on Wednesday, it will mark the first time since 1983 that the Supreme Court will consider the constitutionality of legislative prayers — a year that precedes the service of any of the current justices on the Supreme Court. In that case, Marsh v. Chambers, the Supreme Court considered a challenge to the Nebraska legislature’s practice of employing a Presbyterian minister, who lead the legislature in prayer for 16 years, and concluded that such prayers did not violate the Establishment Clause.

The interpretation of the Establishment Clause, however, has long been a contentious issue at the Supreme Court, with controversies ranging from the display of the 10 Commandments outside courthouses to prayers in public schools. The Supreme Court’s seminal 1971 case Lemon v. Kurtzman established a three-pronged test for Establishment Clause cases. In order for a law or practice to comply with the Establishment clause, it must first have a secular legislative purpose; second, it must have a primary effect that neither advances nor inhibits religion; and third, it cannot foster government entanglement with religion.

The Lemon test, however, has not been uniformly applied in Establishment Clause cases, and faces a dubious future, as at least five of the current justices have expressed disagreement with the test. In the 1984 case Lynch v. Donnelly, Justice Sandra Day O’Connor suggested the Court use an Endorsement Test, whereby government laws and actions would be found to violate the Establishment Clause if a reasonable observer would view the law or action as having either the purpose or effect of endorsing or disapproving religion. When the Second Circuit decided the Galloway case in favor of Galloway and Stephens, it used the Endorsement Test to conclude that the town’s prayer practice and the selection of predominantly Christian clergy would lead a reasonable observer to conclude that Greece was endorsing Christianity as a religion, and thus declared the practice unconstitutional.

With the retirement of Justice Sandra Day O’Connor in 2005, however, the Supreme Court has lost its chief champion of the Endorsement Test. In the 1992 case Lee v. Weisman, Justice Anthony Kennedy instead suggested the Court ought to adopt a Coercion Test, which holds that the Establishment Clause ensures that the government cannot “coerce anyone to support or participate in religion or its exercise, or other act in a way which establishes a state religion or religious faith, or tends to do so.” In Weisman, Justice Kennedy wrote for the Court that prayers led by religious leaders in public school graduation ceremonies violated the Establishment Clause as a form of religious coercion.

In Town of Greece, Galloway and Stephens have urged the Supreme Court to hold that the prayer practice “puts coercive pressure on citizens to participate in the prayers.” They argue that citizens attend meetings to participate — to be sworn into office, be honored, fulfill educational requirements, or request rezoning permits. Because this coercion is paired with a specific religion, Galloway and Stephens argue that the practice is “doubly unconstitutional.”

The town of Greece, however, urges the Court to adhere to the Marsh precedent and uphold the town’s prayer practice. In Marsh, the Supreme Court upheld the state of Nebraska practice, arguing that the long tradition of opening legislative sessions with prayer — dating back to the time of the nation’s founding — pointed to the constitutionality of the practice. The town of Greece argues that the Supreme Court on Wednesday should continue to stand by the Marsh decision and allow the town to continue its prayer practice. The town of Greece enjoys the support of approximately half the states, members of the House of Representatives, and the United States government, which received 10 minutes of oral argument time to support the town’s position.

The support of the United States, however, comes with a caveat: that the actual content of the prayers may impact the constitutionality of the prayer practice if “it does not proselytize or advance any one, or disparage any other, faith or belief.” Should the Court follow the United States’ brief, the town of Greece’s prayer practice could be declared unconstitutional owing largely to the heavily Christian nature of the prayer sessions.

When the Court gathers for oral arguments on Wednesday and again for its Friday conference to vote on the case, it will have many decisions to make. The Justices will have to decide which test to use to analyze the constitutionality of the prayer practice under the Establishment Clause, and whether to put the final nail in the Lemon test’s coffin. They will have to decide whether the content of the prayers impacts the constitutionality of the legislative prayers. They may need to decide whether their chosen test conflicts with Marsh, and if it does, whether the historic nature of legislative prayer sessions justifies any exception to an Establishment Clause rule. And in the end, they will have to decide whether legislative prayer practices — which regularly take place in both the Congress and in dozens of state and local governments around the country — can continue.

Alexander Fullman is a Marshall Scholar pursuing graduate studies in political science at the University of Oxford’s Department of Politics and International Relations.

Recent Constitution Daily Stories

Seven Supreme Court cases to watch this week

Racial slurs and football team names: What does trademark law say?