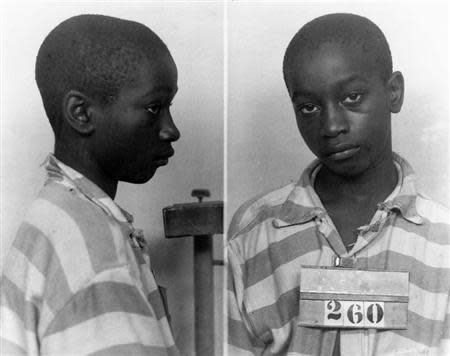

New trial sought for South Carolina teen executed for 1944 murders

By Harriet McLeod SUMTER, South Carolina (Reuters) - A 14-year-old black teenager who was executed in South Carolina in 1944 after a one-day trial for the murders of two white girls was innocent and deserves a new trial to clear his name, lawyers told a judge on Tuesday. George Stinney Jr., the youngest person to be executed in the United States in the past century, was convicted by an all-white jury in 1944 of killing the two girls, ages 7 and 11, in the small mill town of Alcolu, South Carolina. Stinney was put to death less than three months after the murders. Now, lawyers say newly discovered evidence and witnesses justify reopening the case, even though there is no precedent in South Carolina for doing so. "His rights were snuffed out," lawyer Miller Shealy Jr. said. "This is something that needs to be expunged, that needs to be addressed." Circuit Court Judge Carmen T. Mullen told more than 100 people crowded into a courtroom in Sumter, S.C., including two of Stinney's siblings, that she would determine whether he was given a fair trial but not whether he was innocent or guilty. The judge did not dispute that justice fell short in the case in which Stinney's lawyers did not call any witnesses and his family was run out of town. "No one here can justify a child being tried, convicted and executed in 80 days," Mullen said. "Not much was done for this child when his life lay in the balance." Police said Stinney confessed to killing Betty June Binnicker, 11, and Mary Emma Thames, 7, who left home on their bicycles to look for wildflowers on March 23, 1944, and never returned. Their bodies were found the next day with their skulls crushed. Police arrested Stinney after he told someone he had seen the girls by the railroad tracks that divided the segregated town of Alcolu. On Tuesday, nearly 70 years after the first trial, the judge heard from several of Stinney's survivors, including Amie Ruffner, Stinney's younger sister. Ruffner testified that on the day in question she and her brother had taken their cow to graze near the railroad tracks. She testified that the girls passed by on bicycles and asked the siblings where they could find maypops, a type of fruit. After news spread that the girls had disappeared, Ruffner said that her father and Stinney joined the search party. The next day, Stinney was taken away. "They said he killed those girls and I knew that was a lie," Ruffner said. Asked why the family did not take legal action to protest the outcome of the case sooner, Ruffner said the family did what they could, even reaching out to celebrities. "There was nothing we could do," Ruffner said. State prosecutor Ernest "Chip" Finney III has argued against a new trial. No official account of the original court proceedings exists, so there is no way to establish that Stinney's trial was unjust, he said. "Back in 1944, we should have known better, but we didn't," he said. (Reporting by Harriet McLeod; Writing by Colleen Jenkins; Editing by Edith Honan and Grant McCool)