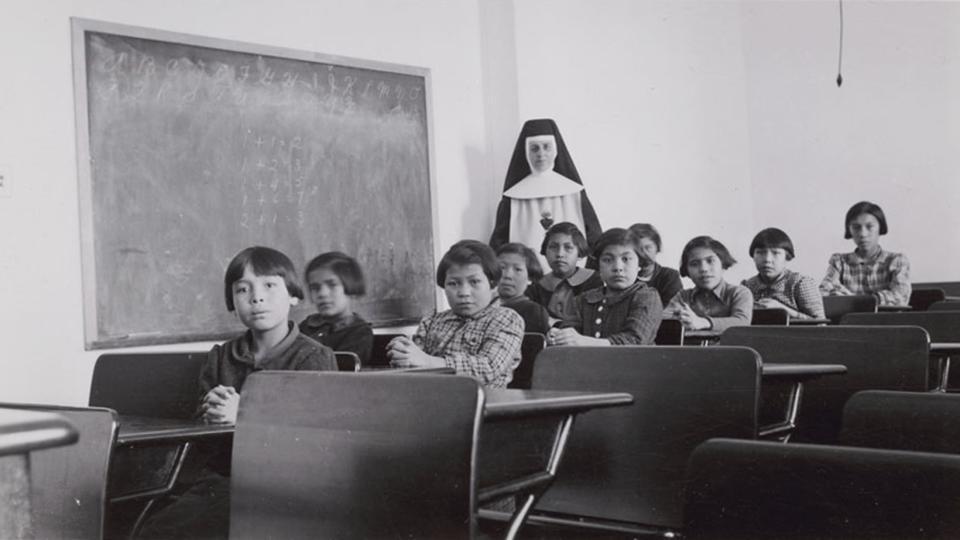

Canadian panel calls for redress, healing after ‘cultural genocide’ at Indian residential schools

Report caps 6-year inquiry into government's roundup of aboriginal children

The Canadian government’s former policy of removing aboriginal children from their families and placing them in special schools amounted to “cultural genocide,” according to a new report.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada released the findings of its six-year research project, consisting of 6,750 interviews with survivors and witnesses of abuse at Indian residential schools across the country.

“There we had a primary goal, and it was to so-called ‘civilize’ the so-called ‘savages’ and to Christianize them,” Marie Wilson, one of the group’s three commissioners, said in a video interview. “And to do everything that we could so that over the course of time they would be fully assimilated into Canadian society and there would be … no more ‘Indian problem.’”

The commission, which was established in June 2008, officially ended with a ceremony at Rideau Hall in Ottawa on Wednesday afternoon; it included the creation of a garden of paper hearts that symbolizes the first step toward reconciliation.

Hundreds of kids to join residential school survivors to plant a "heart garden" at Rideau Hall #cbcott #ottnews pic.twitter.com/pb3NvEb6WR

— Hillary Johnstone (@hill_johnstone) June 3, 2015

Major Canadian politicians, such as Prime Minister Stephen Harper, were in attendance, but many North Americans still do not know what happened to children at Indian residential schools for nearly 150 years.

This story of how the Canadian government passed laws and policies that legally permitted separating thousands of native children from their families and communities is not widely taught, Wilson said.

More than 150,000 children were taken from their homes, and more than 4,000 died, according to the commission.

The last of the schools, which were run by the government and churches, closed its doors in 1998.

The commission released a summarized version of the report Tuesday. It defines cultural genocide as “the destruction of those structures and practices that allow the group to continue as a group.”

In dealing with aboriginal people, the Canadian government tried to destroy political and social institutions, seized land, restricted movements, banned languages, persecuted spiritual leaders and confiscated religious objects, according to the findings.

“And, most significantly to the issue at hand, families are disrupted to prevent the transmission of cultural values and identity from one generation to the next,” the report reads.

“There was a tremendous amount of physical abuse. There was a far greater amount of sexual abuse than anybody ever knew when we started having this conversation,” Wilson said. “And it has left devastating impacts in the communities and in families.”

In some cases, the abused schoolchildren, now adults, told the commission that these were learned behaviors and they “did the very same thing to their children,” according to Wilson.

The commission issued 94 calls to action for redress and reconciliation. These entail preserving languages and cultures, strengthening legal protections for children, eliminating educational gaps between aboriginal and non-aboriginal youths and adopting the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

“There are already solutions in place that can help us move forward on reconciliation,” Justice Murray Sinclair, chairman of the commission, said in a release. “The U.N. Declaration is an example of this. We need to begin incorporating and utilizing these solutions.”

The governments of Canada, the United States, Australia and New Zealand have been hesitant to embrace the U.N. declaration as anything more than aspirational, because it calls for aboriginal peoples to retain the right to consent on issues related to their lands and resources, the New York Times reported.

The government is concerned that this might give aboriginal groups veto power over decisions affecting great swaths of territory, according to the broadsheet.

Canadians need to learn about aboriginal history and the current conditions under which they live, according to the commission.

“There are many who will pull down the blinders and pretend that this isn’t their issue,” commissioner Chief Wilton Littlechild said in the release. “We are calling on you to open up your mind, to be willing to learn these stories, to be willing to accept that these things happened. This is not an Aboriginal issue, it’s a Canadian issue.”

The final report, which has not yet been released, will span six volumes and more than 2 million words. It is being translated into six aboriginal languages.

Wilson said people can no longer cling to their ignorance of these injustices, and he said they are invited to join the national conversation about what Canada has been, what it is and what they want it to be.

“It’s true that most of us alive today had nothing to do with the schools and knew nothing about it. We’re not taught about it,” she said. “But it is also true that we live in the present and we are that ones who will be responsible for the future.”