U.S. extends Special Immigrant Visas: A small break for America’s endangered Afghan allies

The impending inauguration of Donald Trump as president brings plenty of uncertainty for many immigrants and refugees. But last month, after a hard-fought battle in the Senate, Congress guaranteed that a program to provide visas to Afghan nationals who assisted U.S. troops and now face retaliation from the Taliban will remain intact through the coming presidential term.

Since 2014, the Afghan Special Immigrant Visa (SIV) program has been reauthorized regularly for a year at a time. But last year, buried deep within the 700-plus-page National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) for 2017 signed by President Obama just before Christmas, was a provision to extend the program for four more years.

Though seemingly unobjectionable, the program’s extension had to overcome significant resistance before narrowly making it into the final version of the NDAA that landed on the president’s desk.

Last May, Sen. Jeanne Shaheen, D-N.H., introduced an amendment to renew the program through 2017 and authorize 4,000 additional visas. But despite the bipartisan support of Senate Armed Services Committee Chairman John McCain, R-Ariz., and ranking member Jack Reed, D-R.I., the amendment didn’t even get a vote and was left out of the version of the NDAA that first passed the Senate in June.

While efforts to extend and expand the SIV program have encountered challenges in the past, Shaheen told Yahoo News that “they were much harder this year,” blaming anti-immigrant sentiment whipped up by Trump during the presidential campaign. The version that finally passed trimmed the 4,000 visas Shaheen had sought to just 1,500 for 2017, with no commitment to specific numbers in subsequent years. (Those admitted under the program may request to bring their families, so the total number of refugees will be greater.) After it was first established in 2009, the Afghan visa program set out to provide 7,500 visas over five years. Congress voted to extend the program for another year in 2014 and again in 2015, allocating a total of 7,000 additional visas, but still the visa supply has fallen short of demand. The State Department estimates that more than 13,000 Afghans currently await approval for applications for special visas, but as of last October, there were only 1,632 remaining visas available (PDF).

“I think the anti-immigration rhetoric has had an impact on our ability to get what we need for this program,” Shaheen told Yahoo News. “There were a few people, prominent people, in the Senate who did not want to see any additional visas granted.” Among the amendment’s chief opponents were Senate Judiciary Chairman Chuck Grassley, R-Iowa, and Sen. Jeff Sessions, R-Ala., head of the judiciary subcommittee on immigration and Trump’s pick for U.S. attorney general.

Shaheen credited McCain, who led a bipartisan coalition to get the provision passed.

Although she said she could “only theorize,” Shaheen suggested that passing a four-year extension reflected “a recognition that this has been harder to do.”

Betsy Fisher, policy director at the International Refugee Assistance Project (IRAP), which provides legal aid and policy advocacy for refugees around the world, said she was pleasantly surprised to learn that the program had been extended through 2020. Still, she expressed concern that only 1,500 visas would be provided.

It’s good to have “some reassurance that Congress intends to keep this program running for the next four years,” Fisher told Yahoo News. “But without visas to help the people who are submitting applications, that extension won’t result in a path to safety for any more people.”

IRAP estimates that, every 36 hours, one Afghan is killed because of his or her association with the United States.

Ensuring that there are enough visas to accommodate those who desperately need them is “crucial,” Fisher said. “It’s not just the right thing to do, but it sends a message to our friends and our enemies that we take care of the people who work alongside our soldiers and our diplomats.”

Shaheen agreed.

“Obviously we were hoping to get more visas,” she said. “But when the defense authorization bill [initially] left the Senate, it didn’t have any SIV visas in it and it didn’t extend the program.”

Now that the program is guaranteed to exist through 2020, she added, “we can work on a yearly basis to get additional visas.”

But closing the gap between applicants and visa allocations is just the first step. A Senate report found, in 2010, that “resettlement efforts in many U.S. cities are underfunded, overstretched, and failing to meet the basic needs of the refugee populations they are currently asked to assist.” (PDF)

Sacramento is home to one of the largest concentrations of Afghan refugees in the U.S. Since 2010, 2,000 special visa holders and their families have resettled in the California capital, and more are still trickling in. But for many of those Afghans lucky enough to receive one of the coveted visas, the promised better life in America leaves much to be desired.

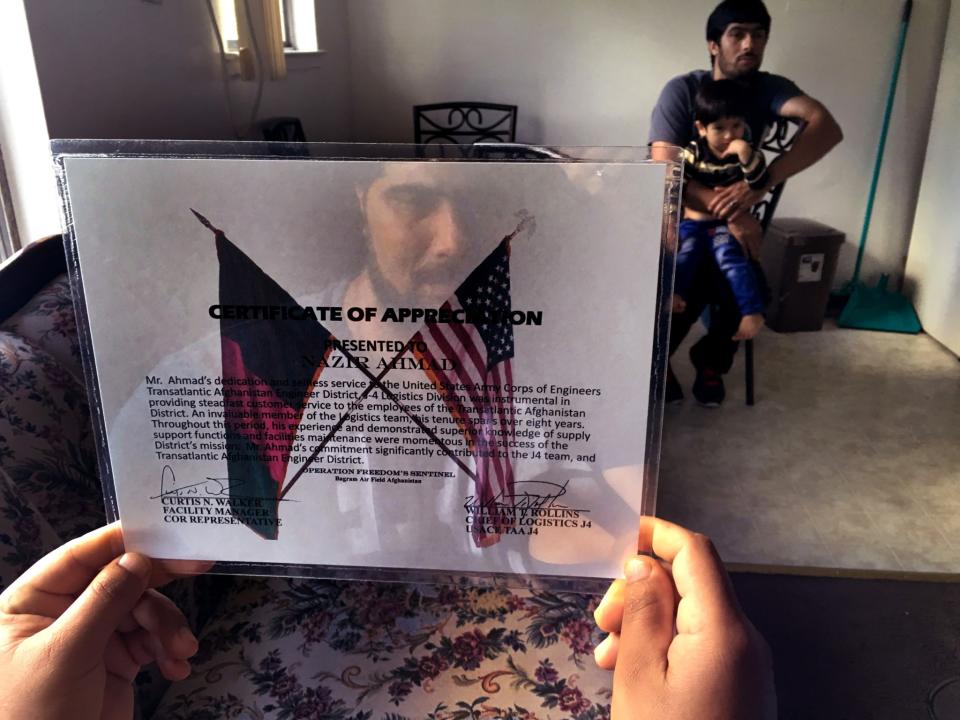

Last summer, the Sacramento Bee published a powerful series of articles documenting the dismal living conditions of Afghan SIV holders in Sacramento. After risking their lives to assist American troops — typically as translators and interpreters — and escaping retribution by the Taliban, they were at the mercy of a threadbare resettlement system that’s left them desperate, disillusioned and in some cases suicidal.

Doctors, architects, engineers and other educated Afghans arrive in the U.S. only to learn that their degrees are invalid, relegating them to work menial jobs at minimum wage. Provided with little more than some “welcome money” from their local resettlement agency — generally between $40 and $150 per person, depending on family size — Afghans struggle to find affordable housing upon arriving in the U.S.

“You see that they have this incredible hope when they come here for a better life than where they’ve left and that they’re really struggling to make it to anything,” said photojournalist Renée Byer, who spearheaded the Sacramento Bee series. “Nobody wants a free handout, they just want opportunity and they’re not getting it.”

Beyond the economic — and not to mention cultural — hurdles encountered upon arriving in America, Byer also learned that the limited funding of the resettlement agencies meant little resources for many special visa Afghans who suffer from PTSD.

“They’ve witnessed some horrible scenes,” Byer told Yahoo News. “They’ve seen some of their family members killed and they’ve been on the front lines. … Imagine what they’ve witnessed already before they even come here, then they come here expecting this American dream, to be confronted with a broken system.”

In response to the series, Rep. Doris Matsui, D-Calif., called for the federal Government Accountability Office to conduct an investigation of the resettlement process for Afghans with special immigrant visas.

“My goal is to make sure that SIV holders and their families in Sacramento – and all over the country – have the opportunity to live with dignity and integrate into their communities,” Matsui told Yahoo News via email. “This is about showing compassion for the brave people who helped our troops, despite the dangers they faced in their home country for doing so.”

Matsui added that while it was “extremely important,” to extend the SIV program for another four years, “it’s still essential that each year we authorize more visas so that the thousands of people waiting to escape harm’s way have the opportunity to participate in the program.”

Accomplishing this, Matsui predicted, “will be a challenge,” but she said, “I’ll keep advocating for the authorization of more visas in the years ahead.”

Shaheen said she was concerned for the future of the program. “The whole anti-immigration debate has been unfortunate, but to have this get caught up in that has been even worse.”

However, Shaheen said she has already had the chance to raise the issue with Trump’s pick for defense secretary, Gen. James Mattis, as well as secretary of state nominee Rex Tillerson. Both men were receptive, she said, noting that Mattis in particular “acknowledged that he knows how important this program has been for our men and women on the ground.”

After all, she added, securing visas for those who’ve risked their lives to help American troops is not just an immigration issue; it’s a matter of national security.

“If we don’t make good on this promise, how can we expect to get help in the future if we go into another country?” Shaheen asked. “We can’t afford to leave and say, ‘Sorry, you’re on your own. If you get killed, too bad for you.’ That’s not in America’s interest.”

Read more from Yahoo News: