UK to cut top income tax rate to 45 pct

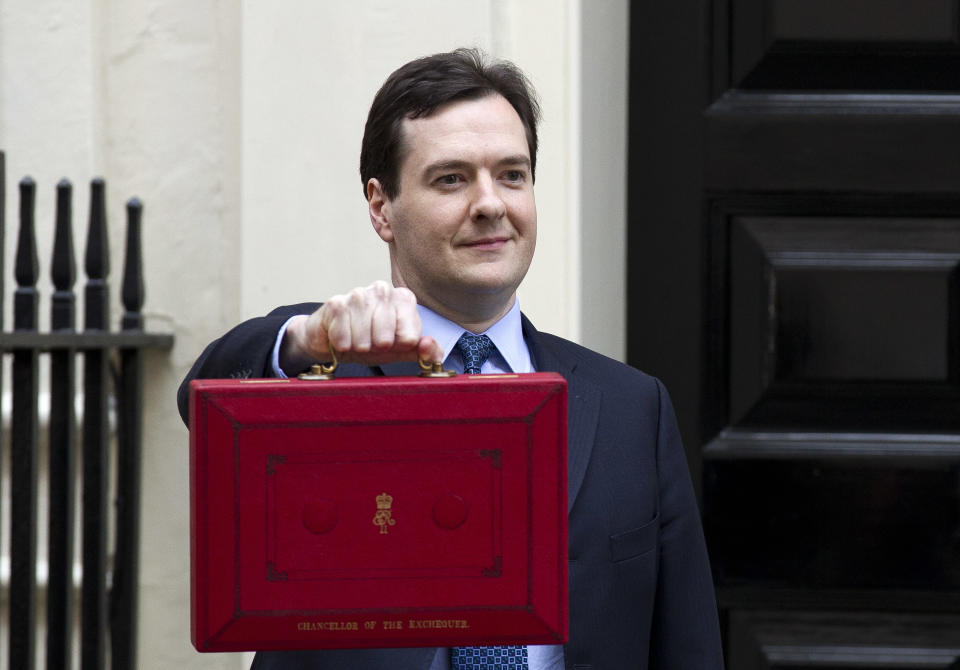

LONDON (AP) — Britain's finance minister has cut the rate of income tax for the country's wealthiest citizens but imposed a raft of measures to prevent tax avoidance and a hefty new charge on expensive property sales in an attempt to spread the burden of austerity across the U.K's taxpayers.

In his annual budget statement Wednesday, George Osborne said he was cutting the top rate from 50 percent to 45 percent by April next year on incomes over 150,000 pounds ($239,000) a year. He argued that the original higher rate did not yield as much as expected, partly because the rich were able to avoid the tax.

Osborne sought to deflect criticism that the coalition government was being soft on the wealthy by announcing a big hike in the level at which Britons start paying tax, to 9,205 pounds ($14,500). There are doubts, however, whether the poorest will reap the full reward, given they may lose some benefits.

One group that appears disappointed by changes announced Wednesday were retired people. Age UK, the country's leading lobby group for pensioners, criticized Osborne's plan to scrap the age-related tax allowance, saying it would "affect those with modest pensions and savings for their retirement." Documents published alongside the budget indicate that the Treasury may reap a windfall of around 3.3 billion pounds from the changes to the tax allowances to pensioners.

The 50 percent tax rate was introduced by the previous Labour government as part of austerity measures introduced in the wake of the banking crisis that led to the country's deepest recession since World War II.

"Together, the British people will share in the effort and share the rewards," Osborne said. "This country borrowed its way into trouble, now we're going to earn our way out."

The leader of the Labour opposition Ed Miliband pounced on Osborne's decision to cut the top rate of tax, mocking him for his oft-repeated mantra that "we're all in this together."

"After today's budget, millions will be paying more while millionaires pay less," Miliband said.

Osborne insisted that the rich should pay a bigger proportion of their income than the poor and said he was offsetting the cut in the top rate by other taxes on wealth, including a new 7 percent charge on the sale of houses valued over 2 million pounds ($3.2 million), up from 5 percent.

Most of those residences are located in London — a city that has become a second home of choice for many of the world's super-rich who have driven up the cost of homes to levels that are unaffordable to the vast majority of Londoners.

Tony Ryland, a senior tax partner at London Chartered Accountants Blick Rothenberg, said the changes will have "a major effect on the London housing market, potentially driving away overseas buyers."

Overall, the budget measures were broadly neutral. Osborne has little room for maneuver, given the government's primary plan to dramatically reduce borrowing and recent warnings from credit ratings agencies that they could cut the country's cherished triple-A rating if public finances don't improve.

The government's debt-reduction program has been rewarded in the money markets to an extent, even though the economy has flatlined and unemployment stands at a near 17-year high. Unlike other big borrowers in Europe, Britain — the biggest European economy that does not use the euro — has enjoyed super-low borrowing rates, making the deficit easy to finance.

Osborne said he was asking the Treasury to examine whether Britain should start issuing bonds of duration longer than 50 years to lock in the current historic low interest rates. The yield on Britain's ten-year bond is around 2.3 percent, in line with the equivalent U.S. rate.

Economic growth this year will be 0.8 percent, up from a previous forecast for 0.7 percent, according to the Office for Budget Responsibility, an independent agency tasked by the government to compile projections.

Osborne said Britain was likely to avoid a technical recession, officially defined as two consecutive quarters of negative growth. In the last three months of 2011, Britain contracted by a quarterly rate of 0.2 percent.

In 2013, Osborne said Britain's economy would likely grow 2 percent, slightly lower than the previous forecast of 2.1 percent. The projected growth rates remain below the long-run average of 2.5 percent.

Meanwhile, the budget deficit in the current fiscal year, which ends March 31, will be 126 billion pounds ($199 billion), 1 billion pounds less than expected. As a percentage of GDP, debt will peak at 76.3 percent in 2014-15, lower than previously thought.

Analysts said the statement was a bit brighter than those of recent years, but that there's a long way to go before Britain has recovered from the shock of the last few years.

"The vast majority of the cuts in public spending lie ahead," said Ian Stewart, chief economist at accounting and consultancy firm Deloitte.

Osborne outlined a range of measures he hoped would kick-start growth. A cut in the corporation tax rate by a further percentage point in April takes the rate down to 24 percent. By 2014, he said the rate would be 22 percent.

The coalition government also announced plans for taxpayers to get an online record of where their tax payments go. The move follows a 2011 initiative in the U.S. where taxpayers can enter their income tax amounts in to a government website and are given a "receipt" showing how the money was spent by government.

Osborne also announced that tax relief now given to film productions would be extended next year to producers of video games, animation and "high-end" television programs such as "Downton Abbey."

"Not only will this help stop premium British TV programs like 'Birdsong' being made abroad, it will also attract top international investors like Disney and HBO to make more of their premium shows in the U.K.," Osborne said.