So you want to form your own state? It may take a while

Voters in five Colorado counties said on Tuesday they want to form their own state. But the breakaway regions face almost impossible constitutional and political obstacles.

If you didn’t catch the story, 11 counties decided to post a question in Tuesday’s elections in Colorado about leaving their current state to form a new state called North Colorado. Five counties approved the vote in a straw-poll referendum and asked their commissioners to pursue secession.

The North Colorado movement supporters claim that their counties have little in common with more urbanized parts of the state, and they are unhappy with state-wide laws about gun control and energy standards.

The question posed in the 11 counties was this: “Shall the Board of County Commissioners of ___ County, in concert with the county commissioners of other Colorado counties, pursue becoming the 51st state of the United States of America?”

After their limited victory, the movement’s supporter’s switched course and said they will try a different tactic: redrawing Colorado’s state senate to resemble the United States Senate, so each county would have the same number of representatives.

And while that move would surely encounter legal issues, the idea of carving out a new state from an existing state was a non-starter.

Before and after the vote in Colorado, most analysts and media types were focusing on the steep constitutional hurdle involved in splitting a state in two.

In Article 4 of the Constitution, there is a process for admitting new states, including ones that are split off from existing states.

“New States may be admitted by the Congress into this Union; but no new States shall be formed or erected within the Jurisdiction of any other State; nor any State be formed by the Junction of two or more States, or parts of States, without the Consent of the Legislatures of the States concerned as well as of the Congress,” says Section 3 of the article.

And in fact, two states have been formed since 1789 by a legally approved secession process from an existing state. In 1820, Maine was created as a state independent of Massachusetts, as part of the Missouri compromise.

In 1863 West Virginia became a state during the Civil War under unusual circumstances, after a Union-approved government was named for Virginia, from which West Virginia then seceded. (Tennessee also joined the Union in 1796 as a former part of North Carolina, but it was considered a government territory for an interim period.)

The constitutional barrier for splitting a state, based on those facts, seems steeper than even creating new amendments. If you are keeping score at home, there have been 17 amendments passed since 1789, and two states directly formed from other states.

The most-significant barrier is political as well as constitutional. As we’ve documented before in the cases of Puerto Rico and the District of Columbia possibly seeking statehood, the addition of one new state to the Union creates two new Senators and at least some new Representatives in the House.

With the balance of power so close in Congress, a compromise would need to be reached to admit an equal number of Democrats and Republicans as new members.

So in North Colorado’s case, a second new state would need to be part of any statehood deal, in a scenario like the one that occurred with Hawaii and Alaska’s addition to the United States in 1959.

One possible candidate could be Baja Arizona, a southern region of the state that has a secession movement. And there has been an on-going debate for years in California about the distinct differences between the northern and southern parts of the state.

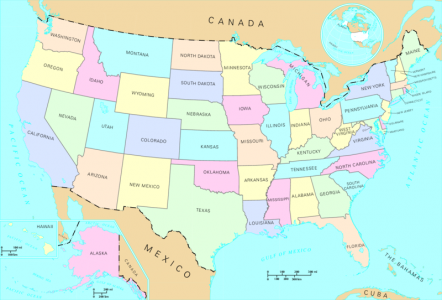

The oddest candidate is the Northwest Angle, a remote region of Minnesota. The township has approximately 120 people and it was created by a mapmaker’s error. It is actually attached to Manitoba and only accessible by land through Canada.

In 1997, the Angle’s residents threatened secession during a fishing-rights dispute. Cooler heads prevailed, and for now, the tourist spot remains part of Minnesota.

Recent Constitution Daily Stories

Constitution Check: Would a new U.S. constitution cure Washington gridlock?

The day Abraham Lincoln was elected President

Town of Greece v. Galloway: Legislative prayer sessions and the Establishment Clause

Racial slurs and football team names: What does trademark law say?