Weather Prediction's Come a Long Way Since Super Bowl I (Op-Ed)

David Hosansky is manager of media relations and a science writer at the University Corporation for Atmospheric Research (UCAR). This Op-Ed was adapted from a post to UCAR's AtmosNews. Hosansky contributed this article to LiveScience's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

Now that we're within a few days of the Super Bowl, we can get increasingly detailed official National Weather Service (NWS) forecasts for the big game. As of Thursday afternoon, NWS forecasters were calling for a high of 51 degrees with a 30 percent chance of rain mainly before 1:00 p.m local time in East Rutherford, N.J.. If the forecasts hold — and we all know that three-day forecasts are not perfect — this means the first outdoor Super Bowl in a northern city won't have to be postponed.

But NFL officials would have no idea what to expect if weather predictions today were as primitive as they were at the time of the first Super Bowl in 1967. Perhaps that's why they played it safe and scheduled that game in Los Angeles.

Back at the time of Super Bowl I, forecasts from the U.S. Weather Bureau (the forerunner of today's NWS) went out just 48 hours. Without advanced satellites and dual-polarization radar systems; high-end supercomputers to run models of the atmosphere several times a day; and the decades of research that have shed light on the oceans, cloud microphysics and so many other factors that influence our atmosphere, people had very little idea of what the weather was going to be like beyond the next day.

Consider this forecast for a late January afternoon in Chicago, just a few days after that first Super Bowl:

//

*/Issued at 345 PM Wednesday January 25th/***

*Thursday...Cloudy with rain or snow likely. High in the 30s. Northeast to east winds 10 to 18 mph. Chance of precipitation 50 percent.*

*Thursday Night...Rain or snow likely. Low in the lower 30s. Chance of precipitation 50 percent.*

*Friday...Rain or snow ending.*

None of the detail to which we've become accustomed. Nothing about how much rain or snow might fall, let alone whether the rain would likely turn to snow overnight or when people could expect the heaviest precipitation. And nothing extending into the weekend.

A few hours later, forecasters provided a bit more detail, warning of a greater than 90 percent chance of precipitation in 24 hours and hazardous driving conditions. On Thursday morning, they predicted that it would snow four inches or more Thursday afternoon. And that was it.

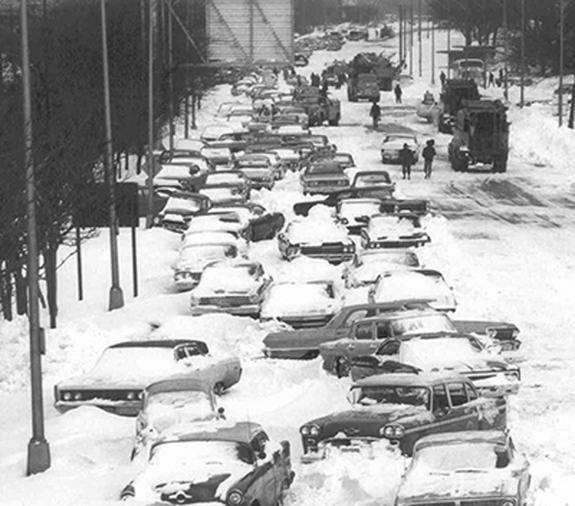

Residents had little warning that Chicago was facing its worst blizzard on record. That the city would be hammered by 23 inches of snow with 4-foot to 6-foot drifts. That 60 people would die, O'Hare Airport would be closed for three days, and the area would suffer more than $1 billion of damages in today's dollars.

Can we take a moment to celebrate how much weather forecasts have improved since the time of the first Super Bowl?

While there are certainly forecasts that go awry, the public is far better prepared than ever. Computer models go out as far as 16 days, and meteorologists can begin to get a feel for the possibility of some major weather events, if not their precise location or timing, 10 days or more in advance. In 2012, the extremely unusual track of Superstorm Sandy, with its left turn into New York and New Jersey, was first suggested by computer models a full week before the storm's devastating landfall.

Researchers are making sure that the improvements are going to continue. Here are a few new developments by the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR) and their collaborators at universities and government labs into advancing both short- and long-term forecasts:

– Scientists from around the world are combing through findings from a 2011 Indian Ocean field project, DYNAMO, which examined the key factors that influence the onset of an atmospheric event known as the Madden-Julian Oscillation on weather events around much of the globe. For example, the oscillation can set off atmospheric waves that trigger storms in the United States more than a week later while affecting weather patterns for 1 to 3 months into the future.

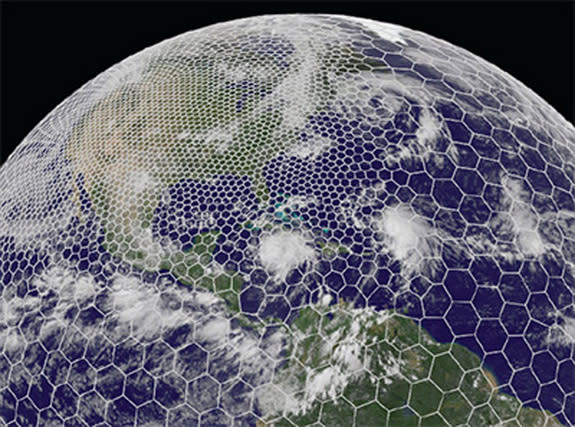

– Scientists at NCAR and the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) have developed a promising new tool, the Model for Prediction Across Scales, which enables researchers to run computer simulations of the entire globe while zooming in on specific geographic regions. In recent tests, MPAS successfully depicted a cluster of severe Midwest thunderstorms more than four days out, and tropical cyclones in the Pacific up to six days in advance.

– A broad group of researchers at NCAR, government labs, and universities have launched a three-year, national project to develop 36-hour, fine-scale forecasts of incoming energy from the sun over specific sites. While the project, funded primarily by the DOE, is designed to help utilities anticipate solar-energy output, it also offers the promise of improving shorter-term predictions of cloud cover.

– Scientists have associated a pattern of high- and low-pressure systems in the upper atmosphere with a heightened likelihood of the onset of major heat waves in the United States 15 to 20 days later. The upper-atmosphere pattern is also being analyzed for potentially providing a 15- to 20-day advance signal of an elevated likelihood of other types of weather events, such as major storms and flooding.

And that's just weather. NCAR researchers and their collaborators are also making strides into predicting the behavior of long-lived wildfires, better guiding aircraft from turbulence, and forecasting air quality over specific areas several days in advance.

There are limits to what people can predict. The atmosphere may be too complicated for meteorologists to ever confidently forecast, for example, what the weather will be like in three weeks over 100 yards of turf during the time of kickoff. And scientists warn there will always be forecasts that go awry.

But the scientific progress since Super Bowl I in 1967 seems likely to continue for some time. We don't know what football is going to look like in a few decades — how strategies may change, whether the extra point will continue to be part of the game. But if the NFL plans again to hold the Super Bowl in a cold-weather venue, the forecast is for better and better prediction.

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. This version of the article was originally published on LiveScience.

Copyright 2014 LiveScience, a TechMediaNetwork company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.