What Robert Caro’s LBJ biography ‘The Passage of Power’ could teach Obama and Romney

During a lost weekend with the latest volume in Robert Caro’s biography of Lyndon Johnson, I was reminded of Gloria Swanson playing the forgotten silent movie star Norma Desmond in “Sunset Boulevard.”

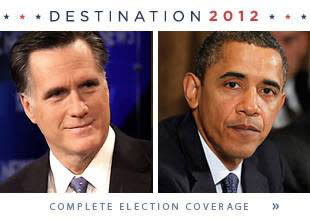

Swanson declares: “I am big. It’s the pictures that got small.” That’s the way I feel after losing myself in Caro’s stirring re-creation of early 1960s politics in “The Passage of Power,” published Tuesday. The presidential race between Barack Obama and Mitt Romney seems like a factory-produced miniature compared to titanic and maddeningly complex historical figures like Johnson and his nemesis, Robert Kennedy. Describing their relationship after John Kennedy’s 1963 assassination, Caro writes in Shakespearean terms, “The President, the King, was dead, murdered, but the King had a brother, a brother who hated the new King.”

Much of this sense of emotional immediacy is a tribute to Caro’s masterly portrait of Johnson, whom he has been pursuing with Ahab-like persistence through four volumes and three decades. So much has been prologue that it seems strange to finally be there—in Volume 4, on Page 336—in an overheated Air Force One on the ground at Love Field in Dallas when Lyndon Johnson, with Jackie Kennedy in her bloodstained dress standing on his left, takes the oath of office on Nov. 22, 1963.

Maybe someday talented writers will bring us this close to an Obama, a Romney, a George W. Bush and a Bill Clinton. But we will have to wait until all the official papers are released, all the oral histories are recorded and once-loyal aides realize that there no longer is a risk to telling the full truth.

But it may be more than just a question of a biographer’s access, knowledge and style. For all the horrors of the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, and for all the personal devastation caused by the economic collapse of 2008 and 2009, the issues that dominated the 1960s were larger. The battle for civil rights was the moral struggle at the core of American history, and the stakes in the Cold War were nothing short of the survival of mankind.

With nuclear missiles and nuclear-armed bombers on a hair-trigger alert, the identity of the man in the Oval Office mattered in ways that are hard to appreciate from the distance of 50 years. Caro’s description of the internal White House deliberations during the 13 harrowing days of the 1962 Cuban missile crisis underscores that while President Kennedy kept searching for a negotiated solution, Vice President Johnson sided with the hawks who demanded immediate air strikes against Cuba—oblivious to the consequences. (Yahoo News columnist Jeff Greenfield, in “Then Everything Changed,” his 2011 collection of alternate histories, suggests that an LBJ presidency in 1962 would have led to nuclear war).

“The Passage of Power” is not merely first-class history like the best Lincoln biographies and the studies of the inner workings of Franklin Roosevelt’s White House. The tumultuous 1960s are still close enough to have a contemporary feel—especially for those of us who lived through them. But Caro’s research also illuminates aspects of the choice facing the voters in 2012, even if today's political leaders do not measure up to the standards of his historical epic.

The Vice Presidency: When Romney unveils his choice of a running mate, he undoubtedly will use words like “partner” and “closest adviser” to stress that his vice president will have the potent policy authority of a Dick Cheney or a Joe Biden. But reliving Johnson’s ordeal in what nominally is the second-highest office in the land is a reminder that a vice president can also be a political eunuch.

During his nearly three years as Kennedy’s vice president, Johnson's public life was filled with petty humiliations: minimal staff, exclusion from major meetings, a dinky 10-seat plane for most of his official travels and near total isolation from the Oval Office. Evelyn Lincoln, Kennedy’s personal secretary, kept meticulous records: Johnson spent fewer than two hours alone with JFK during the final 11 months of his presidency.

Aside from presiding over the Senate and being first in line to replace the chief executive, a vice president has no constitutional responsibilities. If a president chooses not to use his talents—or is threatened by them—then the vice president has little choice but to sulk silently under a form of glorified White House arrest. Johnson said after he left the presidency: “The White House is small, but if you’re not at the center, it seems enormous. You get the feeling that there are all sorts of meetings going on without you, all sorts of people clustered in small groups, whispering, always whispering.”

The Ivy League: At Saturday night’s White House Correspondents' Association Dinner, Obama tweaked Romney over the de facto Republican nominee’s charges of elitism: “We both have degrees from Harvard. I have one; he has two. What a snob.” These elite educational pedigrees have become the norm in campaigns for the White House. In the past quarter-century, only two presidential nominees (Bob Dole and John McCain) have lacked a degree from Harvard or Yale.

It wasn’t always like this. Presidents like Harry Truman, Richard Nixon and, yes, LBJ bristled with class resentment over the inferiority of their educations. Johnson was a graduate of what he called “the poor boys’ school”: Southwest Texas State Teachers College, which had exactly one Ph.D. on its faculty. In contrast, the best and the brightest of the Kennedy White House would have been at ease at the Harvard Faculty Club. As Caro writes of Johnson, “When his assistants are asked to describe his feelings toward the Harvards, they respond with words that have little to do with politics, words like ‘hurt’ and ‘rage’ and ‘jealousy.’”

Smiling Duplicity: If either Obama or Romney have been blessed with the gift of guile, it is a secret left for the memoirs of their closest advisers. In contrast, Bill Clinton had the mind-clouding ability to convince visitors to the Oval Office that the president had said yes when he had, in truth, rejected their pleas. Roy Neel, who was the deputy chief of staff during Clinton’s first term, once told me that part of his job was bluntly informing the credulous who had fallen for the president’s charm that they had been turned down.

But no president—not even FDR—was as adroit as Johnson in convincing people to do what he wanted. In the anguished days after the assassination, Johnson was determined to keep the Kennedy team intact in order to bless his own presidency with an aura of legitimacy. As Caro tells it, LBJ would call each of them to say, “I need you more than President Kennedy needed you.”

Johnson’s gift was his preternatural ability to find that weak spot in the ego where flattery would be the most compelling. With economist John Kenneth Galbraith, Johnson adroitly suggested that he could be a White House insider like his friend Arthur Schlesinger. With United Nations Ambassador Adlai Stevenson, who had been twice defeated for the presidency, Johnson said, “I know, and you know, that you should be sitting behind this desk rather than me.”

Going for the Jugular: Maybe the difference reflects the Bubble Wrap surrounding the modern White House, but reading Caro I got the sense that internal Washington battles were more vicious during the 1960s. I am not talking about congressional gridlock and the lack of bipartisanship in 21st-century Washington, but rather the ability to intimidate others—often those in your own party or administration—to get your way. Among contemporary politicians, by the standards set by Johnson and Robert Kennedy (who earned the description “ruthless”), only Vice President Dick Cheney seemed a throwback to an earlier era in his ability to use a shiv.

When Johnson confronted someone who had double-crossed him, he would often threaten his political demise. Sounding like a Mafia don, LBJ told one errant politician, “I’m going to give you a three-minute lesson in integrity. And then, I’m going to ruin you.” As Caro demonstrates with dozens of examples, Robert Kennedy, when his brother was president, reveled in humiliating Johnson almost for the sheer tearing-wings-off-flies sport of it. Rahm Emanuel sending a dead fish to a pollster early in his career does not measure up to the 1960s standards for hardball.

In 1963, the historian James MacGregor Burns wrote an influential book, “The Deadlock of Democracy,” about the immovable resistance of Southern Democratic committee chairmen in Congress to Kennedy’s legislative agenda. “Our system was designed for deadlock and inaction,” Burns, reflecting the liberal mindset on the eve of Johnson’s presidency, lamented.

That complaint seems eerily contemporary, even if the causes of the breakdown in Congress are different than they were a half-century ago. But maybe part of the failure rests with the inability of contemporary political leaders like Obama and potentially Romney to master the levers of power and persuasion.