Who's who in the U.S. Ebola scare

The news that a pair of American nurses who treated an Ebola patient in Dallas became infected with the virus sparked renewed fears that the outbreak — which has killed thousands in West Africa — could spread to other parts of the country. Here are some of the key figures, including victims, doctors, health officials and organizations, involved in the U.S. fight against the disease.

• Amber Joy Vinson

Amber Joy Vinson, a 29-year-old nurse, became the second nurse who treated Ebola patient Thomas Eric Duncan at Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital in Dallas to be infected with the deadly virus. Vinson was diagnosed with the deadly disease a day after flying from Ohio to Texas, officials at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said. Vinson, a Kent State graduate, was reportedly visiting family near Akron. She was not experiencing symptoms at the time of her return flight, but CDC director Dr. Tom Frieden said during a news conference that she “should not have traveled” after learning in Ohio that she was a potential infection risk. Vinson was among more than 70 hospital workers who cared for Duncan, a Liberian citizen who died from Ebola at Texas Health Presbyterian on Oct. 8. The CDC is now asking all 132 passengers on Frontier Airlines Flight 1143 from Cleveland to Dallas-Fort Worth, which landed at 8:16 p.m. on Oct. 13, to call 1-800-CDC-INFO.

“This is a heroic person, a person who has dedicated her life to helping others and is a servant leader,” Dallas County Judge Clay Jenkins said. Jenkins called the second diagnosis a “gut shot” to the hospital staff, adding that others who treated Duncan may develop Ebola as well. “That is a very real possibility,” he said.

• Nina Pham

Nina Pham, a 26-year-old critical care nurse at Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital, was diagnosed with Ebola on Oct. 12 after treating Thomas Eric Duncan, a Liberian man who last month became the first person to be diagnosed with Ebola in the United States. Duncan later died. Pham, a Fort Worth, Texas, native and 2010 graduate of Texas Christian University, is one of at least 70 people who cared for Duncan before his death. She is the first person to be infected with Ebola on U.S. soil.

Dr. Tom Frieden, head of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, initially characterized the transmission of Ebola from Duncan to Pham as a possible breach in safety protocols. Frieden later apologized, saying he didn't mean to criticize the hospital. On Oct. 13, Pham's dog, Bentley, was rescued by animal control officers from her Dallas apartment and quarantined. "I'm doing well and want to thank everyone for their kind wishes and prayers," Pham said in a statement issued by the hospital on Oct. 14. A friend told the Associated Press that when Pham's mother learned that her daughter was caring for Duncan, Pham told her: "Don't worry about me."

• Thomas Eric Duncan

Thomas Eric Duncan, 42, the first person to be diagnosed with Ebola in the United States, died at Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital on Oct. 8, less than three weeks after arriving in Dallas from Liberia, one of the areas hit hardest by the outbreak. His neighbors in Monrovia told reporters that five days before his flight, Duncan, pictured above, helped a pregnant woman who was convulsing and vomiting get to the hospital in a taxi.

On Sept. 25, Duncan was taken to the emergency room at Texas Health Presbyterian with a fever, abdominal pain and a sharp headache. The hospital said Duncan told them he had not experienced nausea, vomiting or diarrhea — strong indicators of Ebola. He was sent home with a prescription for antibiotics. Two days later, he was rushed by ambulance to the hospital, reportedly vomiting as paramedics put him in the ambulance at the apartment complex where he had been living with family and friends.

Those paramedics are among 70 seven health care workers who are now being monitored for Ebola symptoms. They will be monitored for 21 days, the maximum period it may take for symptoms to appear.

• Dr. Tom Frieden

Dr. Tom Frieden, the 53-year-old head of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta, has been the most visible health official in the fight against Ebola, appearing front and center at news conferences and in television interviews to update the country on the CDC's efforts to keep the virus contained. In early October, Frieden said there were "signs of progress" and that those efforts appeared to be working, since no one Duncan had come into contact with had displayed "symptoms or fever." He added: "And we are confident that if there are any secondary cases there, we can stop the chain of transmission."

Frieden, who has been the CDC director since 2009, has consistently had to walk the line of sounding the Ebola alarm without sounding like an alarmist. "Globally, this is going to be a long hard fight," Frieden said this week. "We can never forget that the enemy here is a virus."

"The plain truth is that we can stop Ebola," Frieden said on ABC's "This Week With George Stephanopoulos" in August. "We know how to control it." And when several U.S. lawmakers criticized the White House for allowing U.S. Ebola patients to be flown back from West Africa, Frieden fired back: "I hope that our understandable fear of the unfamiliar does not trump our compassion, when ill Americans return to the U.S. for care."

• The CDC

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta is ground zero for the federal response to infectious diseases such as Ebola. Headed by Dr. Tom Frieden, the CDC is helping state and local officials with contact tracing, a process used to determine if someone infected with Ebola transmitted the deadly virus to others. "Contact tracing is a core public health function," Frieden said after Duncan's diagnosis. "We do it in a very systematic manner. We interview the patient if that’s possible, we interview every family member, we identify all possible names, we outline all of the movements that could have occurred from time of possible onset of symptoms until isolation." The CDC has also developed an introductory training course to ensure that clinicians providing medical care to Ebola patients have sufficient knowledge of the disease.

• Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital

The Dallas hospital that treated Duncan has come under intense scrutiny for its handling of the Ebola case — and the initial confusion in overlooking his diagnosis. Federal guidelines published in August state that someone in Duncan’s condition and known to have been in West Africa should be placed in isolation and tested for Ebola. Instead, Duncan was given a prescription for antibiotics and sent home. Duncan’s condition had worsened by the time he was brought back to Texas Health Presbyterian two days after being discharged. Hospital officials initially blamed a flawed records system for the mixup but have since retracted that explanation. No other explanation has been given as to how the Ebola diagnosis was overlooked.

• Dr. David Lakey

Dr. David Lakey, commissioner of the Texas Department of State Health Services, has been front and center at press conferences updating the public on the Dallas Ebola cases. “The past week has been an enormous test of our health system,” Lakey said following Duncan's death. “The doctors, nurses and staff at Presbyterian provided excellent and compassionate care, but Ebola is a disease that attacks the body in many ways. We’ll continue every effort to contain the spread of the virus and protect people from this threat.”

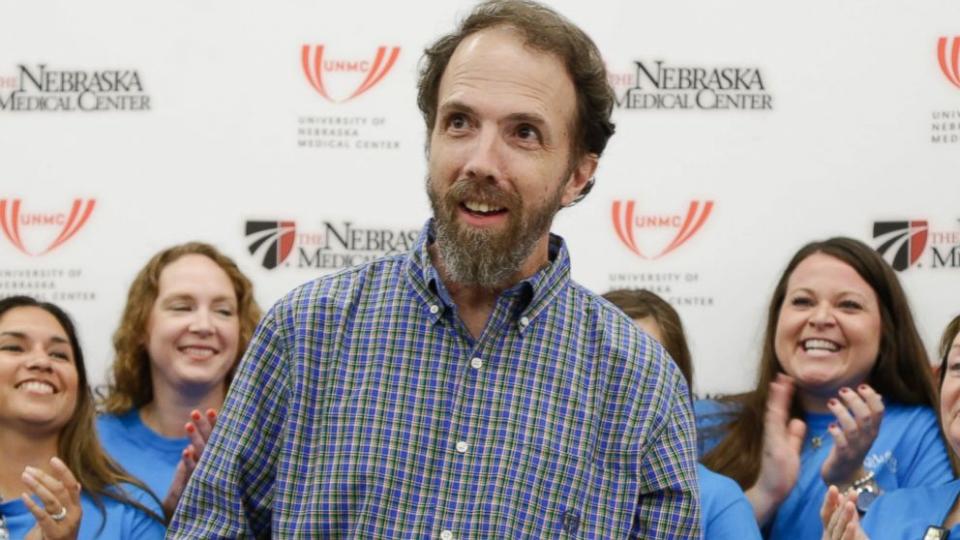

• Ashoka Mukpo

Ashoka Mukpo, a 33-year-old freelance cameraman working in Liberia, was hired to be a second cameraman for NBC News chief medical correspondent Dr. Nancy Snyderman. He tested positive two days later. Mukpo was flown to Nebraska and is undergoing treatment at the Nebraska Medical Center in Omaha, where he received a blood transfusion from Dr. Kent Brantly, an Ebola survivor. On Oct. 13, Mukpo tweeted: "Back on Twitter, feeling like I'm on the road to good health. Will be posting some thoughts this week. Endless gratitude for the good vibes."

• Dr. Rick Sacra

Dr. Rick Sacra, a 52-year-old American aid worker, was allowed to return home to Massachusetts after being treated in the Nebraska isolation unit where Mukpo is currently being cared for. Health officials told the Associated Press that Sacra received an experimental drug called TKM-Ebola, as well as two blood transfusions from Dr. Kent Brantly, at the time that Brantly was recovering from Ebola at an Atlanta hospital. The transfusions are believed to help a patient fight off the virus because the survivor's blood carries antibodies for the disease, but doctors say they can't be sure what helped Sacra recover, because he was receiving multiple treatments. After his recovery, Sacra, who had spent much of the last two decades in Liberia, was admitted to a hospital in Worcester, Mass., and placed in isolation as a precaution after complaining of flu-like symptoms. The CDC later said Sacra had tested negative for Ebola.

• Dr. Kent Brantly

Dr. Kent Brantly, a 33-year-old doctor, was diagnosed with Ebola while working to help the Christian relief organization Samaritan's Purse fight the disease in Liberia. Brantly was flown to Atlanta for treatment at Emory University Hospital, one of four facilities in the country equipped to deal with infectious diseases. He was believed to be the first Ebola patient ever to have been treated on U.S. soil. Brantly received a dose of an experimental serum before leaving Liberia, and recovered. Brantly donated blood to Ashoka Mukpo, the NBC News freelance cameraman who was also diagnosed with the virus, in the hope that antibodies in his blood would help Mukpo's immune system fight the disease. His blood was also donated to Sacra and Pham.

• Nancy Writebol

Nancy Writebol, a 59-year-old American, was infected with Ebola while working as a medical missionary in Liberia, where she helped doctors put on their protective gear and disinfect them as they exited isolation areas. Writebol and another American health care worker, Dr. Kent Brantly, were both flown to the United States, where they were treated in an isolation unit at Emory University Hospital in Atlanta. Both survived. "There were many mornings I woke up and thought, 'I'm alive!'" Writebol said of her recovery. "And there were many times when I thought, 'I don't think I'm going to make it.'"

• Unidentified patient

An unidentified Ebola man was treated for Ebola in Atlanta after being brought to the care facility in early September. A doctor who had been working in an Ebola treatment center in Sierra Leone when he tested positive for the disease, he was determined to be free of the virus and no longer a threat to the public. The hospital never identified the man, in keeping with his family's wishes for privacy.

• Patrick Sawyer

Patrick Sawyer, a 40-year-old top official in the Liberian Ministry of Finance, collapsed in Lagos, Nigeria, on July 20 after getting off a plane from Liberia, where he had been caring for his Ebola-stricken sister. Sawyer died July 25. "Patrick could've easily come home with Ebola," Decontee Sawyer, his wife, told KSTP-TV from her home in Coon Rapids, Minn., where she lives with the couple's three daughters. "Easy. Easy. It's close; it's at our front door. It knocked down my front door."

• President Barack Obama

In the wake of Duncan's diagnosis,President Barack Obama ordered stepped-up screenings for Ebola at five American airports: New York City's John F. Kennedy International Airport, Newark Liberty International Airport, Dulles International Airport outside Washington, D.C., Chicago's O’Hare International Airport and Hartsfield-Jackson International Airport in Atlanta. Those facilities, the White House said, are the ports of entry into the United States for 94 percent of U.S.-bound travelers from the three West African countries in the grip of the latest deadly Ebola outbreak — Liberia, Guinea and Sierra Leone.

• The WHO

The World Health Organization, the world's governing health authority within the United Nations, is responsible for providing leadership on global health matters such as Ebola. According to WHO estimates, there have been 8,900 total reported cases of Ebola since the outbreak began in March, and 4,447 deaths attributed to the virus. On Oct. 14, Dr. Bruce Aylward, WHO assistant director-general, warned that if the global response to the Ebola crisis isn't stepped up within 60 days, "a lot more people will die." West Africa, he said could face up to 10,000 new Ebola cases a week.