Why it might be time to finally replace 'The Star-Spangled Banner' with a new national anthem

In an increasingly anti-racist era when problematic iconography — ranging from Aunt Jemima and Uncle Ben to even the Dukes of Hazzard General Lee car and country band Lady Antebellum’s name — is being reassessed, revised or retired, America’s national anthem, “The Star-Spangled Banner,” seems to be striking a wrong note.

Last week, protesters in San Francisco toppled a statue of the song’s composer, Francis Scott Key, a known slaveholder who once said that African Americans were “a distinct and inferior race of people, which all experience proves to be the greatest evil that afflicts a community.” This week, Liana Morales, an Afro-Latinx student at New York’s Urban Assembly School for the Performing Arts, refused to sing “The Star-Spangled Banner” at her virtual graduation ceremony, explaining to the Wall Street Journal, “With everything that’s happening, if I stand there and sing it, I’m being complicit to a system that has oppressed people of color.” Instead, Morales performed “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” a hymn widely considered to be the “Black national anthem.”

So, is it time for this country to dispense with “The Star-Spangled Banner” and adopt a new anthem with a less troubling history and a more inclusive message? Historian and scholar Daniel E. Walker, the author of No More, No More: Slavery and Cultural Resistance in Havana and New Orleans and producer of the documentary How Sweet the Sound: Gospel in Los Angeles, says yes.

“The 53-year-old in me says, we can't change things that have existed forever. But then there are these young people who say that America needs to live up to its real creed,” Walker tells Yahoo Entertainment. “And so, I do side with the people who say that we should rethink this as the national anthem, because this is about the deep-seated legacy of slavery and white supremacy in America, where we do things over and over and over again that are a slap in the face of people of color and women. We do it first because we knew what we were doing and we wanted to be sexist and racist. And now we do it under the guise of ‘legacy.’”

Activist and journalist Kevin Powell, author of the new book When We Free the World, says it’s important to understand the song’s racist legacy, starting with Key’s bigoted background.

“‘The Star-Spangled Banner was written by Francis Scott Key, who was literally born into a wealthy, slave-holding family in Maryland,” explains Powell. “He was a very well-to-do lawyer in Washington, D.C., and eventually became very close to President Andrew Jackson, who was the Donald Trump of his time, which means that there was a lot of hate and violence and division. At that time, there were attacks on Native Americans and Black folks — both free Black folks and folks who were slaves — and Francis Scott Key was very much a part of that. He was also the brother-in-law of someone who became a Supreme Court justice, Roger Taney, who also had a very hardcore policy around slavery. And so, all of that is problematic. And the fact that Key, when he was a lawyer, also prosecuted abolitionists, both white and Black folks who wanted slavery to end, says that this is someone who really did not believe in freedom for all people. And yet, we celebrate him with this national anthem, every time we sing it.”

“Francis Scott Key, he was a big-time guy in terms of the American colonization of society,” adds Walker. “This was not just a person who just lived in the time period. This is a person who helped define the time period.”

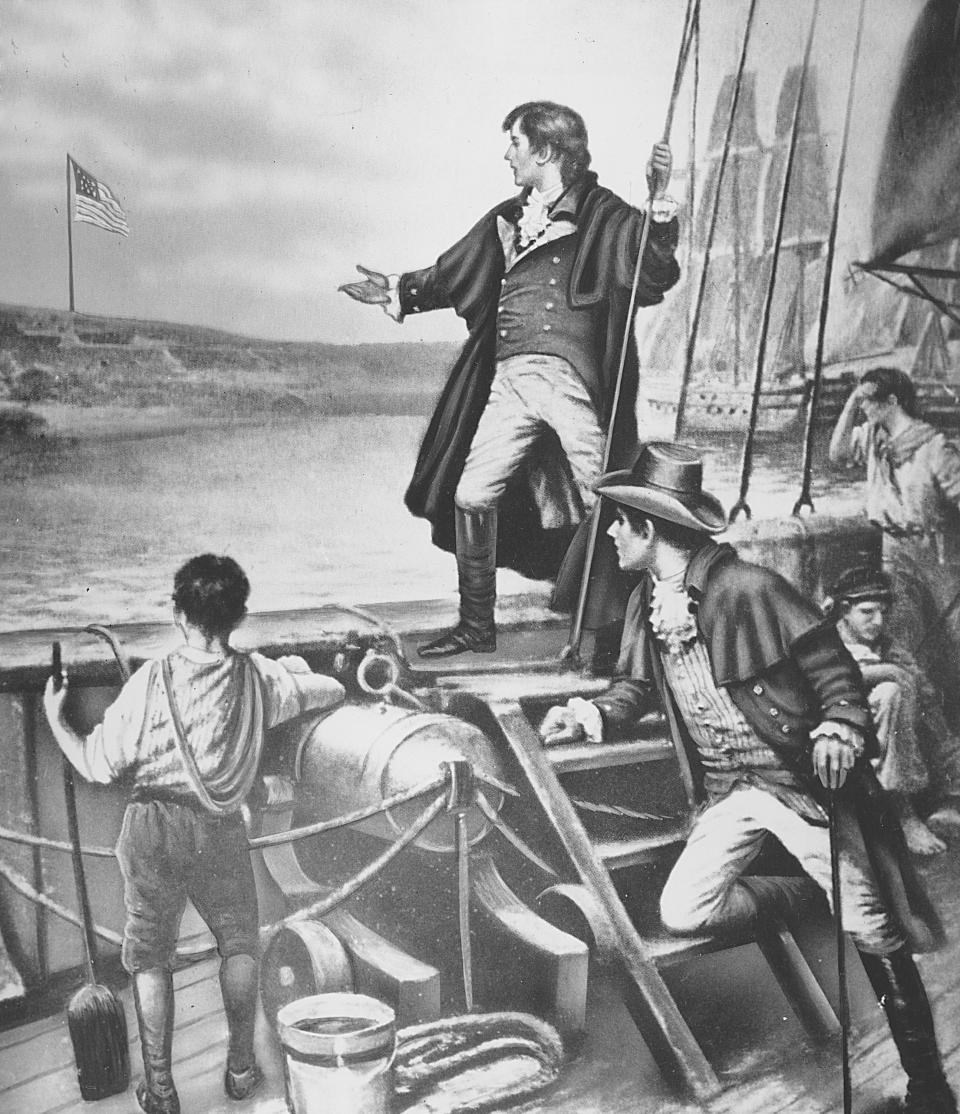

In fact “The Star-Spangled Banner,” based on a poem Key wrote about his eyewitness account of the War of 1812, originally featured a little-heard third stanza that was blatantly racist: “No refuge could save the hireling and slave/From the terror of flight or the gloom of the grave/And the star-spangled banner in triumph doth wave/O’er the land of the free and the home of the brave.” While that version of the song is rarely performed today, Powell has been aware of it for years, and, like Morales, has therefore refused to sing the anthem since he was in high school in the 1980s, when he first learned of its history.

“I grew up in hip-hop,” says Powell, who used to write for Vibe magazine, “and I remember how people would criticize hip-hop for being violent. Yet ‘The Star-Spangled Banner’ is riddled with violence. How are you criticizing a rap song for being violent, but when we get to kindergarten, we are literally teaching children violence through song? I said, ‘I can't participate anymore.’ So I stopped a long time ago.’”

While Powell may have known about the national anthem’s problematic background at quite a young age, Walker understands that many people have only recently become aware of Key’s abolitionism or his song’s horrific third stanza.

“People just don't know history, and everybody's guilty of this. I mean, if I wasn't a historian, I wouldn't know these things. And it took getting a PhD to learn certain things! And I am still learning things every day,” says Walker. “There are students of mine, who are white, who say to me, ‘I'm so upset that I got sugarcoated history my whole life. I feel cheated. And once I found this out, then I don't want to have a part in it.’ Those are the people you see in these rallies. They’re saying that they want to live in a world where those vestiges are gone because they have no reason to be here. And that we need to be about redemption in a society — that if we have wronged someone, we can go back and do our best to fix that. And this one is pretty easy to fix.”

All this being said, Powell doesn’t pass judgement on the many Black artists who’ve performed “The Star-Spangled Banner” at high-profile events in the past — though he predicts that many artists will start refusing to sing it in the near future, in a movement similar to Colin Kaepernick and his supporters taking a knee during the anthem in recent years.

“The issue is not Black people's patriotism. I mean, there's very few folk that are as patriotic as African-Americans,” says Powell. “The way I look at it is, I think what Jimi Hendrix did with ‘The Star-Spangled Banner’ at Woodstock, or the way that Marvin Gaye reinterpreted it and made it a soul song, or Whitney Houston singing it at the Super Bowl in 1991, it became something that belonged to all people, not just folks that thought we should just blindly sing this song. And that's what we do: take these opportunities to perform it because it's a way to showcase one of the greatest gifts to the world, which is music.”

So, if “The Star-Spangled Banner” goes the way of the Confederate flag and Gone With the Wind, what should America’s new national anthem be? Whatever it is, Walker says there should be a formal “vetting process” to make sure the next anthem doesn’t have a terrible past; Powell, for his part, suggests John Lennon’s “Imagine,” which he says is “the most beautiful, unifying, all-people, all-backgrounds-together kind of song you could have.”

But what about “Lift Every Voice and Sing”? That song, written as a poem by James Weldon Johnson in 1900, set to music by his brother J. Rosamond Johnson in 1905, and first publicly performed as part of a celebration of Abraham Lincoln's birthday by Johnson's brother John, was dubbed "the Negro national hymn" by the NAACP in 1919. In more recent years, it has been referenced in Maya Angelou's 1969 autobiography I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings and Spike Lee’s 1989 film Do the Right Thing; it was also performed in 1972 by Kim Weston as the opening number for the Wattstax festival and by Beyoncé during her celebrated 2018 Coachella set.

“[“Lift Every Voice and Sing”] took on a life of its own, because I think when you think about 1900, it’s same kind of ruthless, tragic, white supremacy, white nationalism, and terrorism — the lynchings of black people openly, almost like as if it was a Super Bowl of white folks posing with pictures of dead black bodies hanging from trees, quite literally. And so this song comes out of the tradition of slave plantations, of what became known as spirituals. It was a way for us to make ourselves feel good and empowered in spite of everything that was going on around us. And over time absolutely became the official national anthem for Black America.”

Regardless of whether or not “Lift Every Voice and Sing” could ever officially become the anthem for all of America, Walker thinks its lines like “Sing a song full of the faith that the dark past has taught us” are fitting, and he’s glad that it’s at least being considered as an alternative. “I do like that there's more attention to the fact that there is a thing called ‘Lift Every Voice and Sing,’ that people are rediscovering it kind of like with Juneteenth,” Walker says. “I guarantee you, we had way more people celebrating Juneteenth this past week, knowing what it was, than we’d ever had in American history.

“The difference between then and now, is I — probably like most people — thought that there was no power to be able to change anything, because so many times when women and people of color say something, somebody either pats you on the back and says, ‘It's not that bad,’ or tells you really be quiet, because if you want to move forward, you shouldn’t be a troublemaker,” Walker continues, speaking of the current climate and the national anthem debate. “And so I think you’ve got generations of that because patriarchy and racism and income inequality put people of color and women in those positions. So we just go ahead and sing [“The Star-Spangled Banner”] because we don't want to be the person who's sitting down when everybody else is standing up, don't want to be the person who doesn't have our hand over our heart. We don’t want somebody ask, ‘What's wrong with you?’ where you are in a compromised position already, and they're questioning, ‘Are you an American or not? Go back to Africa if you don't like it here!’ But I think right now, the great thing is that people who have advocated for this in the past and have not been heard are able to double-back now.”

“If you really love your country, if you really are patriotic, then you criticize and challenge your country to be better and do better, not just reinforce things that actually may not be true for all people in the country. … That is what democracy is,” Powell sums up. “If there's a tradition that hurts any part of the society — sexist, patriarchal, misogynistic — then it’s time to just throw it away.”

Read more from Yahoo Entertainment:

• Queen Latifah on affecting social change: 'I feel we're in a pivotal place'

• Flashback: Marvin Gaye grooves up national anthem at 1983 NBA All-Star game

• Master P on Aunt Jemima, Uncle Ben's: 'Those are not real people'

• Chuck D talks Public Enemy’s incendiary new anti-Trump song: ‘This dude has got to go now’

Follow Lyndsey on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Amazon, Spotify.