Why Jon Huntsman is leaving the GOP (not because they’re Communists)

It’s an exhilarating, if somewhat mystifying, experience to find yourself a supporting player in a modern media maelstrom. It’s even more instructive to learn that a dust-up over a few words can obscure a much more significant message.

“My first thought was, this is what they do in China on party matters if you talk off script.”

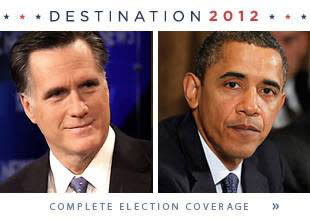

Those words were spoken Sunday night by Jon Huntsman, the former Utah governor and Republican presidential candidate, in a public interview with me at New York’s 92nd Street Y. Huntsman was describing how his comments about the potential appeal of a third party got him disinvited to speak at a Republican National Committee event in Florida.

Before dawn, websites were reporting the quote under headlines like “Huntsman compares GOP to Communist Party of China.” By sunrise, Huntsman was on “Morning Joe,” scoffing that “bottom-feeder” blogs had taken his comments out of context. By midday, BuzzFeed—the target of Huntsman’s critique—had posted a lengthy video excerpt from my interview to argue that no, he had not been taken out of context.

For what it’s worth, I don’t think Huntsman was painting with a brush so broad as to compare the Republican Party with Communist China. For one thing, Huntsman is not yet under house arrest with his Internet access forbidden.

But here’s what the dust-up missed. If you take all of what he said to me over some 90 minutes, it is all but certain that Jon Huntsman is not going to be a Republican much longer.

Yes, he has endorsed Mitt Romney for president, though his expression when he does so has all the spontaneous pleasure of the star of a hostage tape. He cites President Barack Obama’s failure to work the levers of power to accomplish change—intriguingly, he contrasts Obama not with a Republican president, but with Bill Clinton—and Romney’s understanding of the free market and job creation. (Huntsman was animated in scorning Republican candidates who called for a hard line on China or protective tariffs—notions that Romney has enthusiastically embraced.)

The real message he is carrying is that both parties–the “duopoly,” as he calls it—are paralyzed by polarization and inertia, and that the Republican Party in particular is pursuing an “unsustainable” course.

Why, I asked him, shouldn’t Republicans learn from their 2010 midterm victory that an unswerving opposition to Obama is politically profitable?

Because, he replied, “it’s unsustainable. It can’t last more than a cycle or two. ... With the political center hollowed out, the American people are going to say, who’s going to populate the center where you’ll get things done?”

His distance from the party whose nomination he sought goes beyond tactics. When he recalled his first appearance on a debate stage with his rivals, he said he remembers thinking two thoughts. First: “The barriers to entry are very low.” Second: “In a nation of 315 million people ... is this the best we can do?”

If he was including himself, this is a remarkable example of self-deprecation. If he was talking about his rivals, it is an extraordinary indictment, because it includes the man he is supporting for president.

There was more to what Huntsman said than party politics. Listening to him describe his concerns over the emerging generation of Chinese leaders—because they were shaped not by the disasters of the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution, but by enormous economic growth, they're likely to be more nationalistic and “hubristic,” he said—you realize you’re listening to a political figure who served as an ambassador to three Asian nations (Singapore and Indonesia as well as China). His understanding of the Asian-Pacific region surpasses that of any presidential candidate in history.

When he talks of his three urgent priorities for change—term limits, campaign finance reform and congressional redistricting—you can detect a touch of naiveté. Term limits have been a reality for years in California, where they have fed, not halted, a dysfunctional government. Campaign finance reform is beyond the reach of any political leader unless and until the Supreme Court stops thinking of money as speech, leading it to strike down such laws on First Amendment grounds.

You can also hear in his critique of his party the voice of a candidate who tasted enormous popularity—he won re-election as governor of Utah with 77 percent of the vote—and who may have been wounded by the peremptory dismissal of his presidential prospects. (My belief is that his campaign was doomed as soon as he became President Obama’s ambassador to China. In this political climate, no Republican who served under Obama was going to win the GOP presidential nomination.) The charge of “sour grapes” or “sore loser” will not be far from the lips of many Republicans.

Why does this add up to a conviction on my part that Huntsman has one foot out the door of the Republican Party, and is likely placing a bet on his belief that a third party will be increasingly attractive to the electorate, perhaps not this year, but by 2016?

One reason is how he contrasted Republicans from Teddy Roosevelt to Dwight Eisenhower to Richard Nixon with the current party orthodoxy. Could Ronald Reagan be nominated today? I asked. “Likely, no,” he said.

And here’s what he said when a member of the audience posed this question to him: “Given the present direction and positions the party has taken ... is there room for people like you?”

Well, he answered, “I’m sitting here as a Republican.” But after he talked with great enthusiasm about the rise of the unaffiliated voter and the challenge to the political duopoly, I posed one more question.

“Why do I get the feeling,” I asked him, “that if we have this conversation a couple of years from now, you will not be sitting here as a Republican?”

“Because,” he said with a smile, “you’re a good journalist.”

Flattery aside, the answer couldn’t have been clearer.