Will Obama's Julia celebrate a gay marriage?

Is Julia gay? And will she get married now?

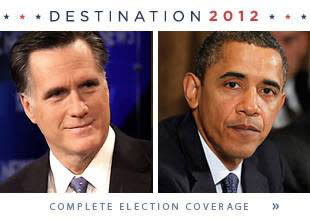

That’s what leapt to my mind Wednesday when President Barack Obama told everyone that he is for gay marriage. That announcement, incidentally, drew huzzahs on the social networks, which tend to mist up over gay marriage in a way that is different from any other issue. Talking about gay marriage involves marginality plus connectivity plus short-form wit. For that reason, it’s an issue ideally suited to Twitter, just as desegregation was the right issue for the heyday of black-and-white newspaper photography.

But back to Julia, the cartoon character of ambiguous personal arrangements at the center of Obama’s widely reviled propaganda slideshow, “Life of Julia.” She is the fictional star of a digital campaign ad that contrasts the ways that Barack Obama’s and Mitt Romney’s policies affect the life of a woman who seems to be single, and yet has a baby. She may need the government, but man does she not need men. So maybe she’s gay!

Not to spoil anything if you haven’t seen it, but in the feature’s rickety logic, Julia fares beautifully when Obama’s calling the social-services shots; things look bleak if Romney had his way.

But that’s not what I took away from “Life of Julia.” What stuck with me is much more self-centered: if I’m honest with myself, I have to admit I have spent my own 42 years deeply, dizzyingly, terrifyingly dependent on men. My father, my brother, the men who hired me and gave me grades and degrees, the men I dated, the man I married, my male colleagues and friends, even my son—without their approval and support I couldn’t have done a thing. I think I would have died.

That’s a scary thing to face. Better to do as men did in the “Mad Men” era—study strong, silent, un-needy types and pray to become them, to repress my reliance on the opposite sex. Those idols were men without women, as Hemingway described them. Now we have women without men.

I’ve studied that Julia for hours. I’ve decided she’s gay to keep myself from facing the fact that she’s probably just a far better woman—morally, politically—than I am. She has her unerring, self-assured, ambitious, balanced, healthy ways. I’m crazy-intimidated by her. She’s some kind of utopian Woman of the Future—a slim, can-do career woman who needs men only for their contribution to conception. Julia has been slagged off as obscenely government-dependent, almost like a right-wing welfare-mom bugbear in yuppie dress, but there’s also not a dad, a brother, a husband in sight.

And now Obama makes it clear he thinks women should get to marry women. Maybe his paradigmatic American is a lesbian who is financially and emotionally free of guys.

Whatever Julia’s status as a composite character, or a beneficiary of munificent government handouts, or an infantilized Canadian type who can’t do jack for herself, Julia is an intriguing cartoon character, as emblematic of her time as Dagwood or Doonesbury or Dilbert. I’d like to see more of her, in fact—in satire or fan fiction or, in a pinch, more productions by the Obama campaign. Julia shows voters something very important: She offers a window on how the federal government sees us.

Julia is openly an equal-pay feminist with a hippie style. In retirement, she works in a community garden. She’s not girlie, she’s always poised, she’s never boy-crazy. Maybe when she wants birth control at 27 it’s to regulate her periods—not because she’s at risk of getting pregnant!

I adore myself under Obama’s gaze. As Julia, I seem extraordinarily serene. I breeze through school without popularity battles or physical insecurities or heartbreak. I’m thinking about schoolwork! As Julia I play with challenging, gender-neutral toys and keep school-spirit stuff and books in my locker at 17, where—in real life, in 1987—the real me had a collage from Vogue and a photo of Rob Lowe.

Mindful of spinal health, as Julia, I conscientiously wear my backpack on two shoulders.

I was too scared and excited by boys and men throughout my life to have risked not seeming feminine. At 22, as Julia, I improbably have iconic modernist furniture, and the kind of big-screened Mac that visual people favor. Not the frills and scented candles I favored. I also have a double bed with two pillows; maybe I’m not sleeping alone.

As Julia, I am nothing if not sensible. Who can stay unmoved by the sight of Julia’s rubber soles in childhood, her sturdy heels in early adulthood, her high heels while she’s on the scene and getting pregnant, and her sensible flats in her dotage? Who can be indifferent to her habit of hiding her hands, so no bitten nails or wedding ring or its glaring absence can be detected?

A brunette, she also appears to go red for a short time; it’s a nice effort. I’m sheepishly impressed by how quickly she loses—I lose! Women lose!—her pregnancy weight, too.

Nowhere is there evidence that Julia is a frenzied filler-out-of-forms and meeter-of-deadlines and maker-of-follow-up-calls—which is how I picture those among my countrywomen who get tons of grants and government goodies.

This sketch of the modern-day Lady Gap Pants—American Woman—is deeply informative. She’s everywoman. Men don’t seem to like her. Pundits who have trashed “Life of Julia” despise her independence from men and her dependence on government programs. In the sequel, we can be sure: Julia won’t care!

Yes, it’s the cantankerous perception of William Bennett, the moralist high-roller, that Julia is a miserable and weak liberal who turns to the government because she has no men to love her, Eleanor Rigby-style. Seconding Bennett, Jennifer Rubin of the Washington Post, called Julia “the liberal feminists’ idealized single woman: no husband and utterly dependent on government.” She asks: “This is progress?”

But Julia is a woman who doesn’t need men. In “Life of Julia,” they’re obsolete. As Bennett and others sense, this weird, almost sci-fi scenario permeates the culture, and provokes anguished cries from men like him. Books and articles embrace the paradigm of a woman who has absolutely no need of men, in conception or marriage or work or anywhere: “The End of Men,” “The Richer Sex” and “Are Men Necessary?”

It’s bold. It sets a high bar for us mortal women. Julia really is like the John Wayne rugged individualists. But those men were fiction—and they made real people, unable to achieve that much autonomy, miserable. Hmm. Just like Julia.