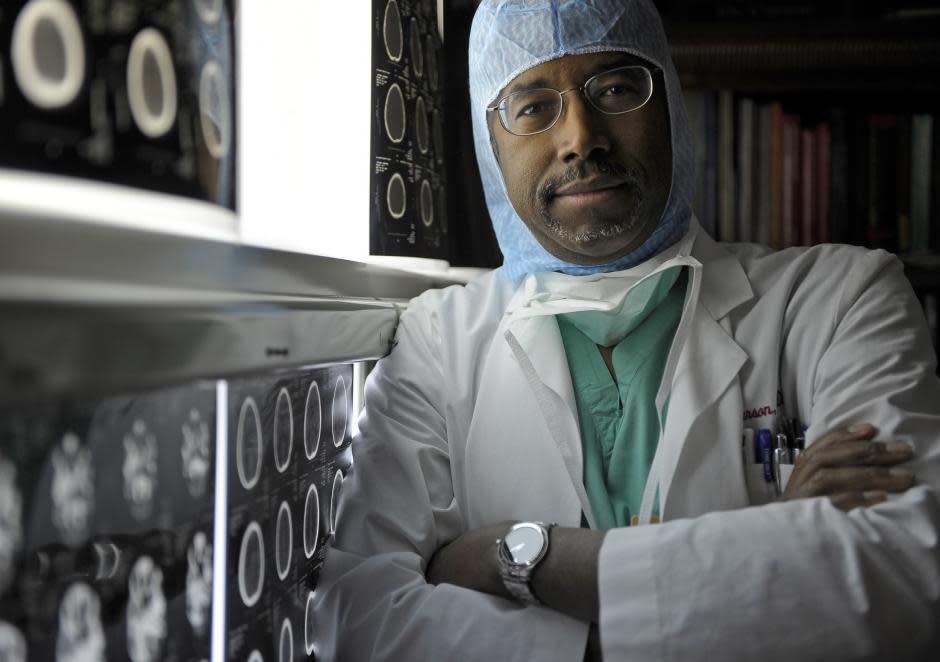

The World Through Ben Carson's Surgical Magnifying Glass

“Now it’s not my intention to offend anyone,” renowned neurosurgeon Ben Carson told a crowd of dignitaries assembled at the Washington Hilton Hotel in 2013. A devout Christian, Carson is surely aware of the proverb about good intentions and the road to hell. He was speaking at the National Prayer Breakfast, an annual affair that’s usually the opposite of edgy—a brief bit of bonhomie (contrived at times) when D.C. puts aside the feuding, at least until the orange juice and coffee have been cleared.

With that opener, it’s not surprising Carson’s 27-minute speech prompted hosannas as well as head scratching. Most of his remarks focused on his remarkable life story, rising from a Detroit ghetto to become one of the world’s most celebrated surgeons. But conservative commentators glommed on to his rant against Obamacare, which came with the president of the United States seated just a few feet from Carson.

Related: Dr. Ben Carson’s Life Story Rests on a Deep Adventist Faith

Carson also took shots at what he called the politically correct media for “crucifying people who say things really quite innocently.” He declared the country is in a death spiral like the one that preceded the collapse of the Roman Empire: “Moral decay, fiscal irresponsibility. They destroyed themselves. If you don’t think that can happen to America, you get out your books and you start reading.”

“Ben Carson for President,” blared the headline of a Wall Street Journal editorial later that week.

Two and a half years later, Carson is running for president and doing very well, a political outsider as laid-back as real estate mogul Donald Trump is in your face. Despite their stylistic differences, Carson and Trump are blazing much the same insurgent path in the GOP primary. After creeping up behind Trump in national polls this fall, Carson has now pulled even or surged ahead in two of the latest surveys, and is leading several polls in Iowa. The doctor’s surge has been as stunning as it has been stealthy. As Trump’s shock-and-awe campaign transfixes the media and the chattering classes, the mild-mannered Marylander, 64, has been quietly building support among conservative voters with his unorthodox and decidedly un-PC appeal.

The retired director of pediatric neurosurgery at Johns Hopkins Hospital has expressed regret for some of the jaw-dropping things he's said—like suggesting serving time in prison can make you gay. But he’s stood by other comments: arguing that a Muslim president would feel compelled to obey Sharia (Islamic law), not American law; suggesting that the Nazis wouldn't have been able to carry out the Holocaust if German Jews had been armed; or equating abortion and slavery.

Those comments have drawn national headlines and a heated backlash. But even more than outrage, Carson’s campaign has provoked bewilderment: How can someone who has such a sparkling scientific résumé make assertions that are so obviously lacking in evidence, the basic building block of scientific study? The gentle, even languid tone in which Carson delivers his controversial views only deepens the contradiction.

In the Victorian-era classic Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, a genial research scientist consumes a potion that turns him into a beast. Longtime friends and colleagues of Carson’s witness a version of that when they see him on TV these days. “I happened to be watching Meet the Press when he said [he would not support a Muslim president], and my family was upset,” says Harold Doley, a prominent African-American Republican and personal friend of Carson’s. He urged them to “give Dr. Carson an opportunity to clarify and expand on his position,” which he did in a flurry of subsequent interviews, though he never fully retracted his initial statement. Doley insists Carson “is not opposed to people based on their religious beliefs.”

For those who knew him as a doctor and philanthropist, Carson’s new career as a politician has been disorienting. Associates of Trump have always known him as a showman, a tornado of hype. By contrast, friends of Carson say the image that’s emerged in the national media is not who he really is. It’s not that they were unaware that he was conservative and Christian, embracing a long tradition of self-reliance in the African-American community. These are values, his friends acknowledge, that he has unabashedly embraced since he was a young man beginning his medical career. Carson’s colleagues at Johns Hopkins, one of the nation’s pre-eminent medical schools, don’t squirm when he proclaims that the world was created in six days, per his Seventh-day Adventist faith, but they struggle mightily with the intolerant zealot being portrayed on cable news, whom they say does not resemble the man they worked with day in and day out for so many years. A man who, yes, was unwavering in his beliefs and unconventional in his approach—but was always humble, constructive and, above all, respectful.

Related: With Soft-Spoken Style, Ben Carson Catches Donald Trump in Iowa

“In real life, he is the most unbiased person I’ve ever met,” says Dr. Henry Brem, director of the neurosurgery department at Johns Hopkins Hospital and a colleague of Carson’s since the 1980s. Brem and others say Carson has a knack for unifying and rallying people—an important skill for a president. “To do innovative things and to break barriers and bring people together—and have everybody pulling in the same direction and get funding to do things—I do think is an extraordinary administrative skill,” says Brem. “How that translates [into running the country] is anybody’s speculation.” But Carson’s career success is based on far more than what went on in the operating room.

At the root of Carson’s worldview is his relationship with God. Carson has belonged to the Seventh-day Adventist Church since he was a Detroit teen with an explosive temper, and he credits Christ with helping him control his anger. The religion's emphasis on living a moral, industrious life and hewing to a fundamentalist interpretation of the Bible explain many of Carson’s contradictions. Adventists are a Protestant denomination, and though they are not part of the evangelical movement, they share similar beliefs in terms of respecting biblical authority and conducting religious outreach. They are literalists about creation being a six-day affair. A recent survey by the Pew Research Center found that 60 percent of white evangelicals likewise reject evolution (as do 47 percent of black Protestants).

The Adventist Church’s world headquarters is just outside Washington, D.C., in Silver Spring, Maryland, which is also the home of a particularly bustling congregation—the Spencerville Seventh-day Adventist Church, which Carson and his family attend. On a recent Saturday morning, the sprawling stone church was overflowing. Despite the blustery weather outside, the main hall felt warm and welcoming, buzzing with a low, cheerful hum as worshippers milled about and families quietly filed into the nave, looking for empty seats in the pews. It felt much like any other Christian church service, except, of course, it was a Saturday, which is when Adventists mark the Sabbath.

Befitting its location in the diverse, middle-class suburb, Spencerville’s congregation that Saturday was a mosaic of senior citizens, teenagers, infants, whites, blacks, South Asians and Latinos. The Seventh-day Adventist Church is the most racially diverse faith in the country, according to Pew, yet another reminder that Carson has been immersed in multicultural environments throughout his adult life. In the presidential race, however, he’s playing almost exclusively to white evangelicals, a powerful force in GOP primaries, yes, but just a narrow slice of the general electorate. Even some of his supporters are frustrated by that, given his background and race. “There needs to be outreach to the African-American community,” says Doley. “I’ve been trying to get that point across to the campaign, with very little to no success.”

Carson has spent almost all of his adult life in Maryland working at Johns Hopkins University, the elite medical school and hospital system located in majority-black Baltimore. Hopkins is where he rocketed from being a serious, young neurosurgery intern in the ’80s (and the rare African-American surgeon at the time) to one of the leading pediatric neurosurgeons in the world, making a name for himself with groundbreaking surgeries such as separating Siamese twins, and rehabilitating children with rare, degenerative brain disorders. His memoir, Gifted Hands, was made into a 2009 TV movie starring Cuba Gooding Jr. It was followed by a slew of other, more politically minded books.

Carson’s emphasis on personal integrity and responsibility has been a constant feature of his life, say those who know him well. Brem, a close friend, calls the 2013 prayer breakfast speech “a typical Ben speech.” He recalls confrontational remarks Carson gave at an NAACP awards gala in 2006, where he was being recognized with the group’s highest honor for achievement. After receiving the award, Carson “acknowledged that everything he achieved had been done on the shoulders of the civil rights movement.” Then, as Brem describes it, he began to “dress down” all its leaders in the room, “saying, ‘You’re not doing enough. We need to help ourselves.’”

Related: Ben Carson Once Studied Fetal Brain Tissue, Now Calls the Research 'Disturbing'

Conservatives have eaten that rhetoric up, embracing Carson as the ideal foil to President Barack Obama. Media baron Rupert Murdoch even suggested on Twitter last month that Carson would be “a real black president,” something he later apologized for. Carson’s own remarks in recent years likening Obamacare to slavery and claiming the president has hurt race relations in America have alienated many in the black community, who lionized the doctor’s groundbreaking medical achievements and philanthropy. But it seems clear, looking back, that the underlying philosophy was always in Carson’s work, if not expressed in such polarizing language. “Ever since I’ve known him, he has been strongly in favor of the individual, individual liberties, individual responsibilities to be the best they can be,” says Dr. Donlin Long, chairman of the Johns Hopkins Department of Neurosurgery from 1973 to 2000 and a longtime mentor to Carson.

That applied to Carson’s work in his community, a priority from the time he first arrived at Hopkins. In his interview for a slot in the neurosurgery residency program, Long recalls the young Carson, then a medical student at the University of Michigan, asking for assurances he could take time off to give talks to schoolchildren in inner-city Baltimore. He was “the only person to ever ask that in an interview,” Long says, laughing.

“When I came to Hopkins, black doctors were extraordinarily rare, particularly in an academic setting,” Carson tells Newsweek. “I realized that what I would be doing could be very inspirational to a lot of kids...who frequently had, as I did, many people telling you what you can’t do and not enough people telling them what they can do.”

So Carson became a proselytizer as well as a physician, taking his message of self-improvement to classrooms around Baltimore and, before long, to the entire country. “On weekends he went away, and the rest of us covered for him,” Brem recalls. “And what he did was, he went into the inner city...every weekend, all over the country. He did that for years and years and years, and eventually that led to the Carson Scholars.” Brem was one of the first board members for the charity, which gives scholarships to elementary and high school students around the U.S. to recognize academic excellence and community service.

Even as Carson worked to lift up inner-city children, he did not emphasize race or ethnicity. The Carson Scholars Fund, established in 1996, is open to any student in any participating school district. It’s always been Carson’s desire “to bring people together and not be divisive on race,” explains Nancy Grasmick, the charity’s interim president.

He’s also rejected a focus on race in his life. When Carson was still a resident, Long recalls approaching his protégé about applying for a National Institutes of Health program for minority doctors. “It was a very nice amount of money that would support their careers and support some additional research,” Long recounts. “And Ben said, ‘Dr. Long, that’s the only insulting thing you’ve ever said to me.’”

For many African-Americans, Carson’s de-emphasis of skin color and his tendency to invoke slavery as a parallel for a variety of current political controversies—he’s compared it to not just abortion but also to Obamacare—have soured them on the doctor. “Academically, he always been a pillar within our community,” says Jamal Bryant, the pastor at Baltimore’s Empowerment Temple. “His work really is well-known and highly celebrated.” Carson even got a shoutout in Season 4 of the iconic HBO series The Wire, when a grade school student in inner-city Baltimore tells his teacher, “I want to be a pediatric neurosurgeon like that one nigger.”

But Bryant, an outspoken civil rights activist, also criticizes Carson’s silence on racial discrimination. “He has not spoken, really, to the injustices that we face right here in Maryland,” says Bryant, who gave the eulogy for Freddie Gray, the 25-year-old from Baltimore whose death in police custody this past spring sparked days of protests and riots. “Every schoolchild in the last 15 years or so has learned who Ben Carson is. That’s a natural constituency” for his presidential campaign, says Doley. “Unfortunately, another natural constituency you might think, would be the African-American constituency. But it’s not there.”

Given Carson’s academic background, one might think that intellectuals could be a political constituency as well. But many of his highly educated peers have struggled with his rejection of mainstream science, including the Big Bang theory and the overwhelming evidence of climate change. A recent piece in The New Yorker, titled “Ben Carson’s Scientific Ignorance,” noted that in a 2012 speech, Carson “made statements...that suggest he never learned or chooses to ignore basic, well-tested scientific concepts.”

Related: CNBC Alters Debate Format After Trump and Carson Complain

Here, too, Carson’s contacts from his life before politics say none of this is new, and the political uproar has led to a caricature of the doctor. Academics, laments Long, have become “quite intolerant.” People have forgotten, he says, that “the whole basis of science is questioning the basis of scientific principles. That either generates the truth, such as they are at the time. Or it will generate strong criticism and perhaps stronger hypotheses.”

Dr. George Jallo, director of the Johns Hopkins All Children’s Institute for Brain Protection Sciences, worked under Carson for a decade and considers him a mentor. Jallo tells Newsweek that Carson’s religious beliefs made him respect the senior neurosurgeon more. “Here he is as a physician, he has a very good foundation of science and also is a religious man,” Jallo says. “His beliefs were thoughtful in the sense that he had a good understanding of both.” Carson’s former colleagues aren’t the only people in medicine who aren’t bothered by his beliefs: Health professionals represented the largest single group of professionals donating to his campaign thus far, according to the Center for Responsive Politics.

Jallo says Carson was notably open, though not doctrinaire, about his religious faith. “He wasn’t afraid to talk about it, and he respected others, so they respected him for that,” Jallo recalls. “He’d pray with them if they wanted to pray with him.” That’s confirmed by one of Carson’s patients, Beth Usher, who was just 7 when she underwent a risky operation to try to cure her chronic seizures. At that time, in the 1980s, Carson and his colleagues were the one team of doctors in the United States performing the procedure, known as a hemispherectomy, where the damaged part of the brain is permanently removed. The night before the surgery, Usher and her family, particularly her 9-year-old brother, were “petrified,” she tells Newsweek. Carson noticed and “took my brother down to the little hospital chapel and prayed with him for like an hour,” Usher recalls. “It was who he was,” says Jallo. “Religion made him who he was.”

Carson’s longtime colleagues have a harder time making sense of some of the social views he has expressed on the campaign trail. The most recent furor was over remarks he made in the wake of a mass shooting at a community college in Oregon. Asked on Fox News what he would have done in the same situation, Carson replied, “I would not just stand there and let him shoot me. I would say, ‘Hey guys, everybody attack him.’” Media commentators promptly attacked him, saying he was criticizing the victims.

Then there was that aforementioned Muslim slight on NBC’s Meet the Press this September. “I would not advocate that we put a Muslim in charge of this nation. I absolutely would not agree with that,” Carson told host Chuck Todd. And in a March CNN interview, Carson said that homosexuality is a choice because people “go into prison straight and when they come out, they're gay.” The doctor later apologized and said he did “not pretend to know how every individual came to their sexual orientation.”

That kind of campaign rhetoric belies Carson’s personable nature and respect for people of all backgrounds, according to people who know and worked with him. They say those traits, even more than his dexterity with scalpels and drills, are what made him an exceptional surgeon. “Ben had a remarkable ability to bring...people together, mainly because he was never interested in his own reputation,” Long says. That’s a rare trait in the high-octane, ego-driven world of surgery, and one that made Carson very popular with his peers.

Jallo says he can vouch for that, recounting Carson’s preparations for the 2004 surgery to separate 13-month-old Siamese twins born joined at the head Lea and Tabea Block, in Lemgo, Germany. Carson first gained fame almost two decades earlier, when as a 30-something neurosurgeon he directed the 70-person medical team that successfully separated another German pair of conjoined twins, Benjamin and Patrick Binder. But he was no less meticulous this time around. Carson brought the whole team of doctors and support staff together to rehearse the procedure and seek out suggestions. He was listening to everyone, “from the electrician” (to discuss contingency plans for a power outage) “to the biomedical engineers to the cleaning person,” Jallo says. “That’s very unusual in my experience—there aren’t very many leaders who have enough confidence in themselves that they open themselves to everyone in their team.”

With patients, Carson was known for his comforting bedside manner, earning him the nickname “Gentle Ben.” He worked with very sick children, a difficult field but one he didn’t shy away from. “I remember him actually getting down on his knees to talk to me at my eye level,” says Usher, who is now 35. She and Carson continue to exchange letters, and she sees him at an annual reunion that brings together fellow hemispherectomy patients.

Though Carson has angered gay rights advocates with his opposition to same-sex marriage and his comment about gays in prison, Brem points out that when Carson was head of Johns Hopkins’s Department of Pediatric Neurosurgery, he trained and mentored openly gay residents, as well as a whole mix of people of other backgrounds and orientations. “He has no prejudice or bias in his own life,” Brem insists.

How, then, does one explain the divisive persona he’s assumed as a politician? Carson sees no contradiction. “My approach is that people are people, and that’s why...I don’t speak on race very often,” he tells Newsweek. “The skin doesn’t make them who they are, the hair doesn’t make them who they are. The brain does.”

As for his concern about a Muslim president, Carson has clarified that he’d accept a Muslim leader if he or she rejected Sharia. “To me, it has nothing to do with faith, it has to do with a lifestyle,” Carson explains. “Islam is more than just religion. It’s a lifestyle, and it does not accommodate separation of mosque and state.”

Doley says Carson’s original comment “was very troubling.” It even prompted him to reach out to close friends who are Muslim, to caution them not to jump to conclusions. But he says Carson’s subsequent explanations have reassured him and other supporters. “Ben is not a bigot; Ben is a great thinker,” Doley says. However, “he does not think in sound bites, and he can’t be expected to speak in sound bites.”

Other friends have come up with similar explanations for the disconnect with what they hear on the campaign trail. Brem hypothesizes that his friend gets himself “trapped” in statements he doesn’t mean. But it’s clearly something Brem is struggling with, pausing as he tries to gather his thoughts. “It’s hard to explain,” he says of the dichotomy between the doctor he knows and the politician. “It’s painful to me.”

Related Articles