'All in' moment for a split-the-difference president

A reluctant commander in chief confronts a growing threat to the U.S. homeland — and to his legacy

Rallying the nation to a war against the Islamic State terrorist group in primetime Wednesday night, President Barack Obama sought to project both resolve and reassurance. America will lead a broad coalition in degrading and ultimately destroying what amounts to a hybrid terrorist army, but will not “get dragged” into another prolonged war of regime change and nation building. That’s a nuanced message as far as war cries go, and Obama seemed dispassionate and at times almost conflicted in delivering it. “I want the American people to understand how this effort will be different from the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan,” he said Wednesday night. “It will not involve American combat troops fighting on foreign soil. This counterterrorism campaign will be waged through a steady, relentless effort to take out ISIL [another term for the Islamic State] wherever they exist, using our air power and our support for partner forces on the ground.”

In some ways that message comports with a president who has an instinct for splitting the difference on matters involving the commitment of military forces. Recall that Obama’s last primetime address to the nation came almost exactly one year ago, when he asked Congress to authorize military strikes on the Syrian regime to enforce the administration’s red line against using chemical weapons on civilian populations. When Congress balked, Obama split the difference, forgoing airstrikes but agreeing to a Russian-crafted plan to remove Syria’s chemical weapons stockpiles instead. After many months of deliberation on whether to surge U.S. troops to Afghanistan in his first term, Obama likewise decided to send fewer troops than the military commanders wanted and, against their advice, to announce a firm withdrawal date. Ditto the more recent decision on whether to leave a residual U.S.-led force in Afghanistan after most combat forces are withdrawn at the end of this year: a smaller-than-requested force of some 10,000 troops, and a firm exit deadline of 2016.

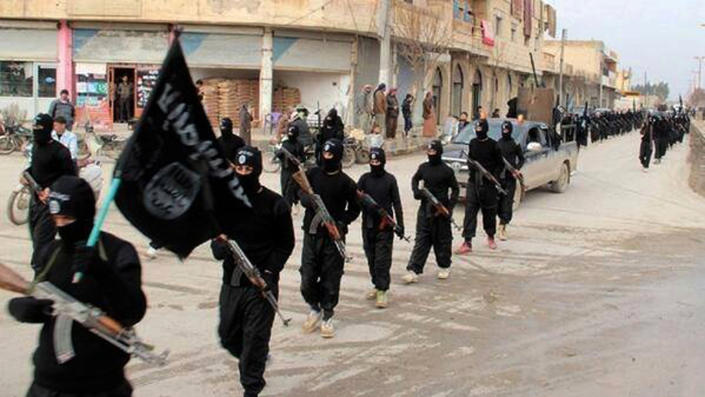

Yet the Obama administration has now realized that the extremists of the so-called Islamic State (IS) are not a “split the difference” kind of foe. As recent events have made clear, they cannot be negotiated with, contained or dissuaded with compromises. They are true believers in the most fundamental sense, eager to eviscerate themselves in suicide operations, to slaughter nonbelievers and captured opponents in mass executions, and to cut the heads off American journalists like James Foley and Steven Sotloff — all in service to their nihilistic vision of a medieval caliphate ruled by tyrants in religious garb. And for more than two years IS has been steadily gaining territory, treasure, lethal weaponry and followers, to include an estimated 1,500 to 2,000 Europeans and Americans with Western passports, according to intelligence sources.

The growing shadow that IS has cast, not only over the region but internationally, some experts believe, is behind Obama’s epiphany that the group is not in the “junior varsity” of the terrorist pantheon that he characterized earlier this year, but rather a growing threat to the U.S. homeland.

“Obama is a very risk-averse president who until now has willfully avoided militarizing the U.S. role in Syria and Iraq, but the realization that ISIL was a growing threat to the U.S. homeland caused a fundamental change in his outlook and risk calculation,” said Aaron David Miller, a distinguished scholar at the Woodrow Wilson Center and a former Middle East adviser to numerous presidents. Obama knows that if IS (also sometimes known as ISIS) were to launch a successful attack on the continental United States during his last 1,000 days in office, said Miller, “it would utterly destroy his presidency. And the one area where Obama has shown a readiness to accept significant risk, including the decision to kill Osama bin Laden, is in counterterrorism operations.”

Indeed, the template for the “comprehensive” strategy that Obama laid out Wednesday night for destroying IS is not the wars of regime change and nation building waged in Afghanistan and Iraq, but rather the secretive counterterrorism campaigns that the administration has executed in places like Yemen and Somalia. The essence of those operations is combining lethal, precision U.S. airstrikes and advanced intelligence-gathering capabilities with U.S. Special Operations Forces training, advising and assisting local troops on the ground.

For a cautious president and White House that have steadfastly resisted becoming entangled in the Syrian conflict — or taking ownership of the fight against IS in Syria or Iraq — that strategy represents a new “all in” mindset. Indeed, in

terms of scope, complexity and visibility, the campaign to dislodge IS from major urban areas and Sunni provinces in Iraq, and attack its leadership and operational centers of gravity in Syria, will prove exponentially more difficult and risky than the hunt for individual terrorists of al-Shabab in Somalia and al-Qaida in the Arabian Peninsula in Yemen. IS has formed alliances in Iraq with former Baathist army officers and Sunni tribes, for instance, both disaffected by the sectarian rule of former Shiite Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki.

The Obama administration gets credit for helping to oust the divisive Maliki from power. The fact that Secretary of State John Kerry was in Baghdad even as Obama spoke yesterday, however, reflects the heavy diplomatic lifting now required to form a true unity government in Baghdad that entices Sunni tribes back under the government tent, and Sunni states such as Saudi Arabia and the Persian Gulf states into the anti-IS coalition. On Thursday Kerry flies to Saudi Arabia, where he is to hold high-level strategy talks with senior Saudi, Egyptian, Jordanian, Turkish and Lebanese officials.

“One of the lessons of the last decade of conflict is that you don’t end a war by simply walking off the battlefield — you just hand the advantage to your enemy," said Ryan Crocker, the former U.S. ambassador to Iraq and Afghanistan, who faults the Obama administration for disengaging from Iraq diplomatically as well as militarily. “Now we have to once again be the catalyst for compromise between the Shiites, Sunnis and Kurds of Iraq, because they simply can’t do it by themselves. The constant message that the United States must now send to friend and foe alike in the region is ‘We’re here, we’re engaged, and we’re not going away.’”

Obama’s decision to intensify airstrikes against IS targets in Iraq, and send an additional 475 U.S. military advise-and-assist forces (on top of the roughly 1,000 U.S. troops already on the ground), suggests preparation for an inevitable offensive by Iraqi security forces to begin retaking critical cities and territory seized by IS during the summer. The recent success of U.S. airpower in enabling Kurdish peshmerga forces to dislodge IS fighters from the Mosul Dam and recapture villages and territory in northern Iraq offers a hopeful blueprint for that larger offensive to come.

Perhaps the riskiest element of the strategy involves Syria, where the U.S. will target IS leaders with lethal airstrikes and ramp up training and arming of more moderate Syrian rebel factions. While the administration does not believe it needs congressional authorization for the airstrikes, it has asked Congress for additional authorities and funds for the train-and-equip mission. It has also won a commitment from Saudi Arabia to provide a training base for the Syrian rebels. The administration has not said what, if any, accommodation it has reached with the regime of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad, which Obama said “will never regain the legitimacy it has lost.”

The fact that the Obama administration has now announced plans to target IS leaders even in Syria and firmly back the moderate Syrian rebels — two moves the White House steadfastly resisted as the Syrian civil war raged for years, against the advice of some of Obama’s most senior foreign policy and national security officials — are the clearest signals to date that Obama has taken ownership of the war against ISIL. If recent history is any guide, that does not bode well for IS leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi and his fellow travelers.

“President Obama’s speech was an important marker, because it indicates that the United States is now going to mobilize an international coalition against ISIL, and that’s pretty much a worst-case scenario for any group,” said retired Army Lt. Gen. David Barno, the former senior U.S. commander in Afghanistan and a senior fellow at the Center for a New American Security in Washington. “We may look back on this as the moment when ISIL became a victim of its own catastrophic success, capturing so much territory and making so many enemies with its brutality that it sowed the seeds of its own destruction.”