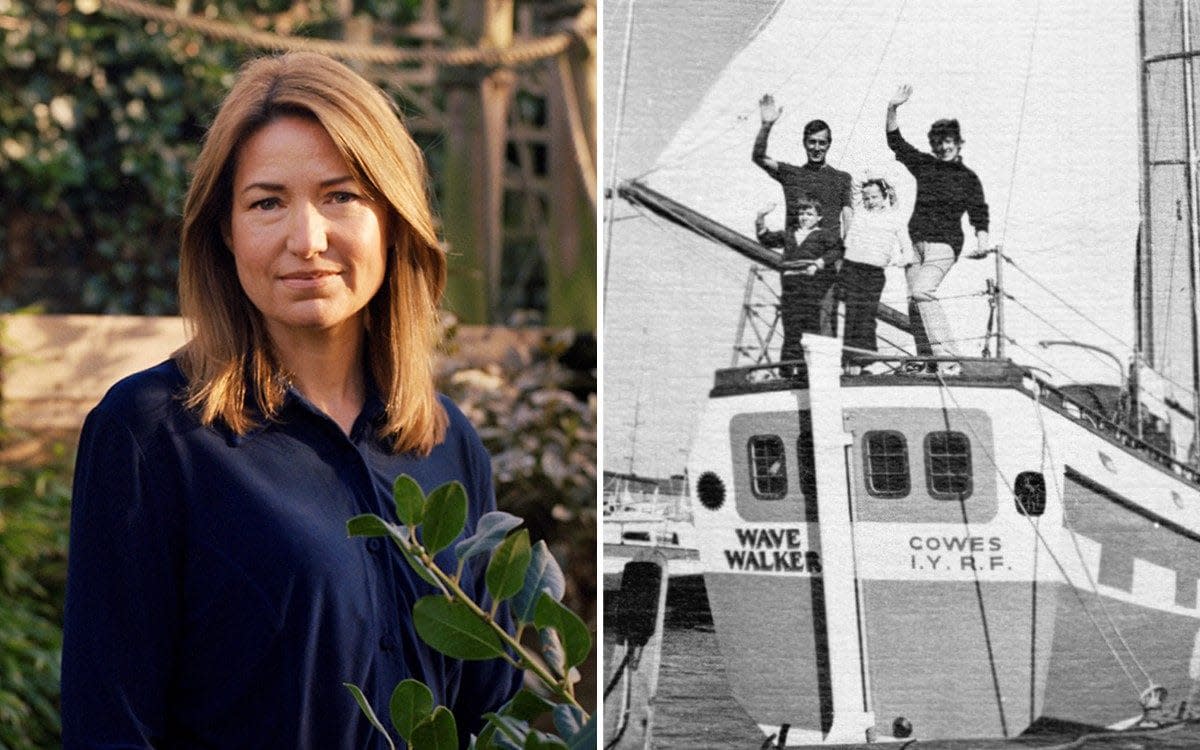

‘My family sailing jaunt turned into a 10-year nightmare at sea’

Suzanne Heywood was six when her parents suddenly announced over breakfast at the family home in Warwick that they would all spend the next three years sailing round the world, retracing the third and final voyage of Captain Cook. They would journey first to South America, then apartheid South Africa, over the southern Indian Ocean to Australia, from Fremantle around to Sydney, on to Tasmania, across to New Zealand, before finishing in Hawaii, to mark the 200th anniversary of Cook’s murder by Hawaiian natives.

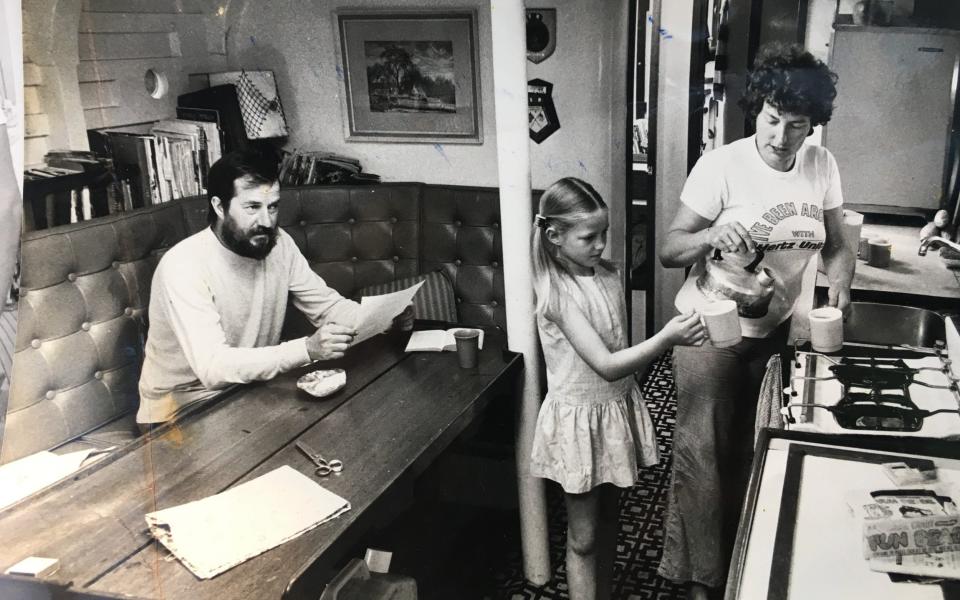

‘I can’t think of a better education than sailing round the world,’ said her father, Gordon Cook (no relation, but a Yorkshireman like the captain). He was a good sailor but not one who had crossed the globe. With Suzanne and her younger brother Jon, their mother Mary – who suffered from seasickness and was ambivalent about boats – and Gordon, there would be a crew on board (which was to change along the way, until it largely comprised untrained volunteers).

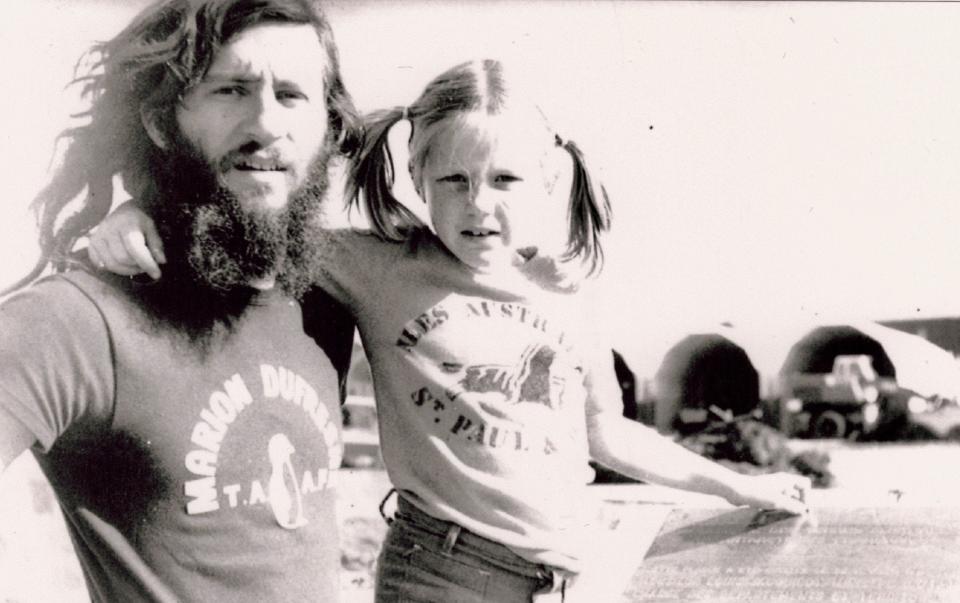

It was, by any stretch of the imagination, an ambitious plan, one that would turn out to be a long nightmare for a girl who boarded happy and healthy, and escaped 10 years later feeling depressed and fighting for her right to be educated. ‘My father wanted to be a hero and my mother wanted to be with my father, and once you get those two pieces in place, it was kind of as simple as that,’ explains Heywood today.

‘It was not the sailing that was the problem; there is something magical about sailing, which other sailors will understand. It was that the choice of voyage was incredibly dangerous and the way in which it was done, with a certain foolhardiness around the details: taking a novice crew on board, never seeming to have any backup, the length of distances travelled involving such small children with no real provision to look after us. We were stateless and invisible.’

While the trip had initially been funded by selling the family home (as well as a family-owned hotel) and vital sponsorship from the hotel group Trust House Forte (complete with its logo on the mainsail), this changed with time. The sponsorship ended and the money ran out. Fees paid by travellers joining the vessel as ‘crew’ (in the loosest sense) – eager to use it as a means of transport – became vital to the continuation of the voyage.

The family set off in July 1976 from Plymouth Sound on Wavewalker, a 70ft schooner. There was only one working child’s life jacket, which went to Jon. Suzanne, by then seven, and her brother would be tutored on board by their parents, both qualified teachers. They would re-enter the UK education system three years later, Gordon and Mary told them.

But Suzanne was not to return to the UK until December 1986, aged 17, her childhood over. The children were overruled in a ‘family vote’ about whether to end the trip in Hawaii (two years behind schedule) when she was 12, and another four years were spent sailing the Pacific. Family relations became strained beyond being bearable, her relationship with her mother toxic, and her attempts to receive an education increasingly desperate.

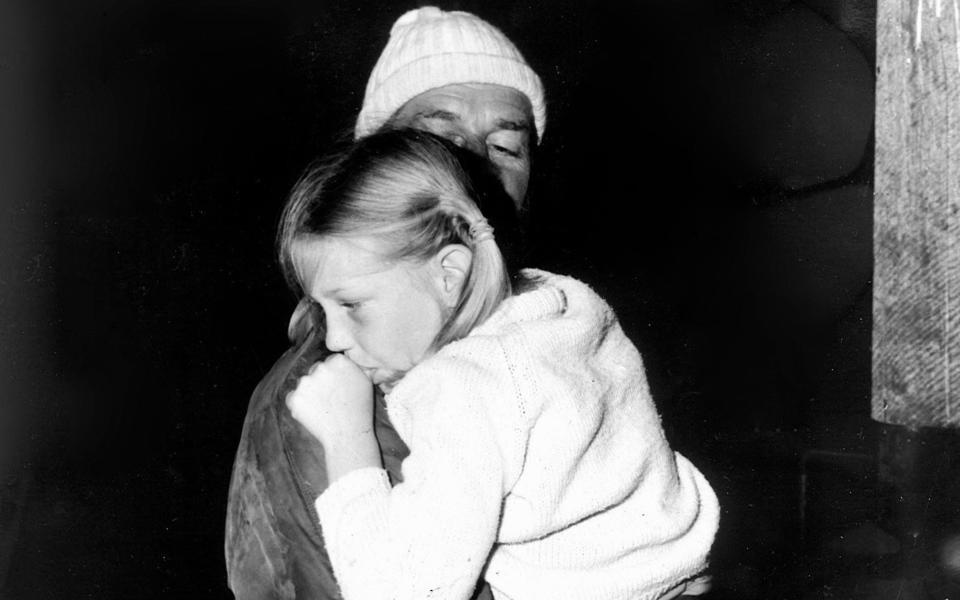

After a decade at sea, she was ‘offloaded’ by her parents in New Zealand, with little money or food, tasked with looking after her brother while they sailed away. In desperation she had telephoned Childline, and finally boarded a flight back to England funded by her father.

‘You walk away from a childhood like mine with various scars,’ she says. ‘I have physical scars but I also have emotional scars.’

Today, we meet in her double-fronted home in Balham, south London, on the eve of the publication of her book Wavewalker: Breaking Free, eight years in the writing and an astonishing almost day-by-day account of that hazardous journey and its legacy. Suzanne Heywood, 54, officially Lady Heywood, is petite (her sex and her stature were held against her on the boat), yet there is a quiet fierceness about her. In 2018 she was widowed, with three teenage children to look after. Her late husband was Lord Jeremy Heywood – the famously intellectually brilliant civil servant, cabinet secretary from 2012 to 2018 – whom she met while working at the Treasury in 1994. He died aged 56, of lung cancer. Four prime ministers spoke at his memorial.

Falling in love with him had brought all the emotional security Suzanne had longed for: ‘One of my big emotional scars was this fear of being abandoned because I was repeatedly abandoned by my parents. I had felt very secure with Jeremy. I knew whatever I did he would never leave… But with my parents, I never had that security of knowing that it would be OK. To challenge them in the way that I [eventually] did in a world where I had no resources and I was on my own was very frightening.’

Her husband, she writes, ‘combined formidable intelligence with the kindness and warmth that were so absent in my childhood’. Her grief surfaces more than once during our conversation, ‘but it’s not complicated’, she says, fighting back tears. ‘When I finally had 12 sessions of therapy I thought it might raise all these issues of abandonment again, of somebody I love disappearing, but Jeremy did not mean to go. I spent half a session talking about him and 11 and a half talking about my parents.’

She has an unplaceable accent, a little Australian, the only country in which she received a small period of conventional education in a school. From correspondence courses on board Wavewalker, against the odds, she got herself to Oxford, then Cambridge for a PhD, then the Treasury and after that McKinsey & Company. She would become one of the management consultancy’s first female senior partners in the UK. She is now chief operating officer of Exor and chair of CNH Industrial and Iveco Group.

Where we sit there are L-shaped sofas and plump cushions. Everything is clean and organised, a long way from life on Wavewalker, where Christmas presents were washed away by storms. Order in adulthood has replaced chaos in childhood, as is often the case for children brought up with uncertainty.

‘People often say to me when they learn of my story, “But you seem so normal!” And I am normal in some way, but I am also an outsider.’

The story she tells – ‘which is from my point of view’, she acknowledges – is about the power of the family myth of the journey versus her reality. Her mother died in 2016, she has been estranged from her father since 2019 because he objected to her writing the book, and she has not spoken to her brother for some time. ‘His experience of the boat was not the same as mine. He was the favoured child. He wasn’t expected to do chores like I was – he helped on deck and didn’t have the same overwhelming desire to study. He didn’t feel the deprivation in the same way that I did.’

The family sailed 47,000 nautical miles (the equivalent of travelling twice round the globe). It was, according to her parents, a decade of adventure and ‘privilege’, an unusual childhood spent encountering different cultures, golden beaches, flying fish, sperm whales and albatrosses that had jumped on board, and meeting Tāufa’āhau Tupou IV, then King of Tonga.

But the reality for their daughter was bleak: hunger; fear (she still has nightmares); violent storms; two shipwrecks; a gendered division of labour, in which she was expected to clean and cook below with her mother, to feed the crew; and a profound disregard for her need to learn.

‘I’m not afraid to die if we’re all together,’ her father told the children. Heywood remembers him throwing her a gun to help repel a group of men trying to get on board. It is a glimpse, through one lens, of exciting derring-do – but through a mother’s eyes the memory is chilling.

Within months of setting off, she almost did die, when Wavewalker hit a storm in the Indian Ocean and she was thrown against the roof of the cabin. The boat nearly sank. She sustained a fractured skull, a broken nose and a blood clot that threatened brain damage. She was operated on seven times by a doctor on the remote Ile Amsterdam, which their father somehow found because he was an expert navigator, using Wavewalker’s big, heavy compass. There was no proper pain relief during the procedures on her skull: ‘I dreaded going to sleep and woke most mornings in a damp sweat from my night terrors.’ Eventually, she left the island on a container ship with her mother and brother to catch up with her father, who had sailed on ahead in the damaged boat.

‘As a child I had started to write a diary because I had such an odd grip on reality. The things that I saw were not always aligned with the stories my parents would tell, which were always, “Weren’t we lucky?” and, “You had such a privileged childhood.” Today, we call it gaslighting. I was literally bobbing around on the ocean with very few stable points of reference…

‘Now, as an adult, I would have got off that boat three years in. Until then, there was a myth that we’d all chosen to be there.’ Then came the ‘family vote’ in Hawaii.

‘Children are humans. They have a right to an education and a right to a social life. There is a UN mandate for children that was clearly breached in multiple ways by my parents.

‘I didn’t have a passport, I didn’t really remember any relatives in the UK. I had no money… I had no ability to do anything apart from this increasingly pervasive sense that I couldn’t get schooling and was miserable. There was no attempt to make any provision of space or even help me get my schoolwork back [from PO boxes]. If there are two meta themes in the book, they are the transformative power of education and this question of the rights of a child versus the decisions made by their parents. I leave it up to the reader to make their mind up.’

She created a canvas cave inside a sail in which to hide and read, and imaginary fellow pupils too. It was a teacher on her correspondence course who helped her get into Oxford to study zoology. A don spotted something original in her essays. (She later told Heywood that she’d played a rare ‘wild card’ letting her in.)

Oxford was not easy with her bizarre background and a lack of parental support, emotional and financial. ‘I think until I got my PhD, I had a point to prove,’ she says. ‘After that, nobody really cares about your childhood.’

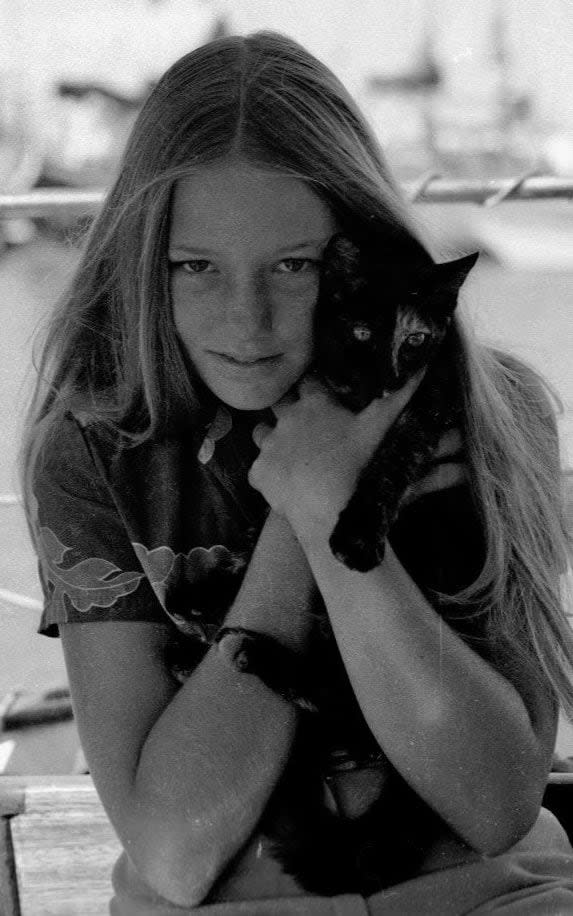

She arrived at university with little more than her diaries, a photo album, a carving from Marovo Lagoon and two childhood comfort toys, Teddy and Barnaby, who had survived the trip too. She shows me one of the pictures she kept. She is on the deck of Wavewalker, hair in plaits, one arm round her father’s neck, the other waving to the reporters who gathered at various points to capture the family on their brave adventure. It was taken at the beginning: she is still young – and smiling.

By the time Jeremy was diagnosed with cancer in 2017, Suzanne was two years into working on the book. She set it aside to write his biography, What Does Jeremy Think?, published in 2021 and a bestseller. Before he died, he made her promise to return to Wavewalker. He also gave his blessing for her to meet somebody else: ‘It was one of a few tricky conversations we had.’

She now has a new partner, James, in business like her and father to three teenage boys. They met via the internet a year or so ago, when she felt ready. Her children, Jonny, 21, and twins Lizzie and Peter, 19, are all at university – Cambridge and Oxford – which her husband did not get to see. ‘That is hard,’ she says.

‘But what I did take from my childhood is massive resilience… I actually fought [my parents] and got away. In some ways, that gives you a huge strength.’

There was, nevertheless, an emotional hurdle to overcome with the book. She had to confront her parents about her version of events (she does, in fact, draw on memories of crew members too). ‘My family would never ever talk about [any] of it. Whenever I tried, the line would be, “Don’t – it upsets your mother.”’

Her relationship with her mother never really recovered from the voyage. ‘The crew noticed. She wouldn’t speak to me, or would refer to me as “her” in front of me. She really disliked me and favoured my brother. We were playing that out in a very enclosed space where I had nowhere to escape. I can see in my diaries all the upset and unhappiness that rises through my teenage years.’

The first draft of the book was bland, because ‘I knew if I went near [the truth] it would offend my parents and if I offended them the whole world would collapse. But they were reacting very badly even to the idea of me writing anything, and I suddenly realised it would make no difference. I decided to write it honestly.’

After her mother’s death, from a heart attack (her parents had returned to the UK in 1991 and ran an internet book company), Heywood found a letter on her parents’ computer called ‘Sue End’. It followed a meeting where she had asked her mother questions. Her father told her to bin it as it had been written in anger. The letter was full of threats and insults. ‘She threatened that if I went ahead with the book, she would write nasty things about me and Jeremy, and try to ruin his career. She also said that I was educationally poor. It was horrible, horrible but helpful – and it set me free.

‘I was never going to get an explanation. She felt no regret, no remorse whatsoever and she was just a very strange person who really, really disliked me. I do think her death makes [the book] easier but I was going to do it anyway.

‘The therapist told me that when you are a child, you don’t question if your world is a good world or a bad world because if you decide it is a bad world, that your parents are not nice people for whatever reason, you are questioning your entire existence. But when you are an adult and have your own life, you can question it. I have my children. I have my friends, Jeremy’s family who I am very close to. I can live with that now.’

She has sent two letters to her father as an olive branch. She says she loves him and does not require an apology. He does, at various points in the story, help her, such as paying for her flight home. As a child, she idolised him, and it is sad how the voyage was to destroy this.

Heywood is ‘a bit nervous’ about his reaction to the book. ‘He can be quite aggressive. But I decided long ago that writing a version that didn’t upset them would be so neutered that it would almost not be worth writing.’

She holds no grudge against the boat. ‘Wavewalker was always a she. She was my home. I loved her. She saved our lives. There is definitely a huge emotional connection to her.’

As part of the process of writing the book, Heywood conquered her fear of the sea by learning to sail, passing the Yachtmaster Offshore exam in 2016. She also attempted to track down Wavewalker, caught in a cyclone while anchored at Malolo Lailai island in Fiji. The boat was never found but she discovered its compass. It sits on a shelf in her study, a reminder perhaps of her strength in getting away to a new life.

Nothing would ever be as terrifying again. In 2021, Heywood threatened to take the Government to court over the handling of a review into the lobbying scandal following the collapse of financier Lex Greensill’s Greensill Capital. ‘My experience on the boat and standing up to my parents in a quiet way, and then keeping it very fact-based, enabled me to stand up for Jeremy.’

Lex Greensill had been brought into the Cabinet Office by Jeremy as an unpaid adviser in 2012. After Jeremy’s death, she has argued, his name was used in ‘attempts to scapegoat [him] to distract attention from the actions of others’. David Cameron, post-premiership, by then a highly paid advisor to Greensill Capital, had been able to lobby the Government intensely in an attempt to secure support for the firm during the pandemic. ‘I’m not sure they knew who I was. I think [Nigel Boardman, the lawyer running the review] thought I was “just a widow”.’

In her study, along with the compass, are various framed scrolls. Before his death, Jeremy became Lord Heywood of Whitehall and was then appointed Knight Grand Cross (GCB), the highest honour in the Order of the Bath. The ceremony was in a hospital meeting room. Heywood shows me the family coat of arms, which they designed together. In the middle, a boat bobs at sea, with two white sails.

She smiles: ‘She had to be in there.’

Wavewalker: Breaking Free, by Suzanne Heywood, is published by William Collins on 13 April, at £20. Pre-order at books.telegraph.co.uk