1,015 U.S. soldiers died in attack: Augusta County man remembers cousin

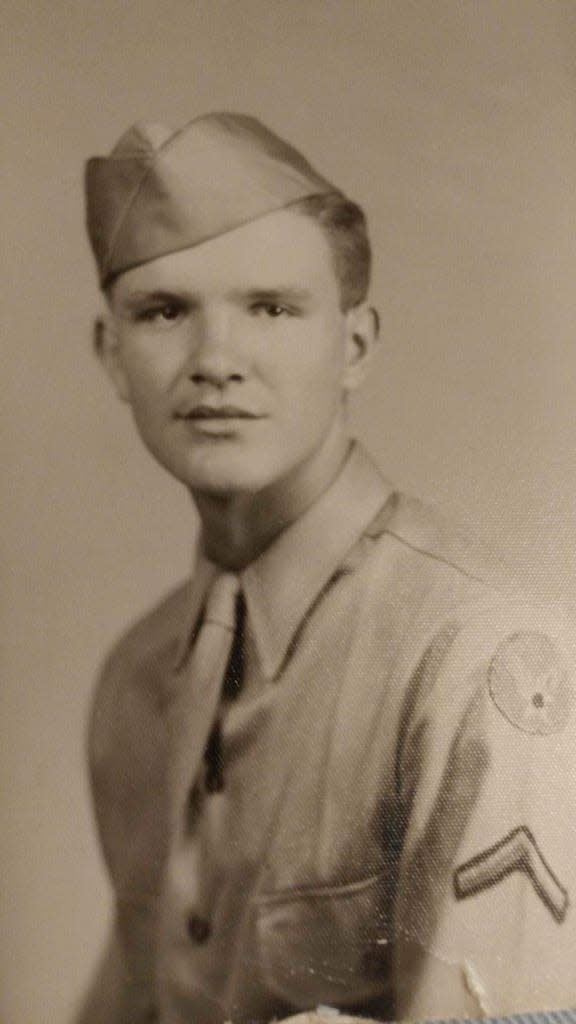

MOUNT SIDNEY — As a boy growing up in Rutland, Vermont, Rick Manning would often see the family marker of the cousin he never got a chance to meet — Raymond J. Mainville Jr. — who was just 19 years old when killed off the coast of Algeria in 1943 during World War II.

Manning, who now lives in Augusta County in Mount Sidney, would usually catch a glimpse of his cousin's marker when visiting those of his grandparents and godparents (Mainville's parents). But with kids being kids, Manning said he never really got around to asking much about his cousin until he was older. It wasn't until about a dozen years ago that Manning began digging for more information about the cousin he never knew.

Mainville was killed while aboard the HMT Rohna, a British transport ship sunk by one of the first-ever radio-guided missiles fired from a German bomber, and was one of 1,015 American soldiers to die in what is considered to be the greatest loss of life at sea in the history of war in the United States. According to The Rohna Survivors Memorial Association, Mainville was a mechanic with the 322nd Fighter Control Squad, Air Corp.

"He didn't want anything to do with boats," Manning said. "There's a little irony in that."

But following the sinking of the Rohna, the War Department declared that the attack be classified indefinitely and ordered all of the survivors to remain silent while the families seeking information were stonewalled, according to filmmaker Jack Ballo, who is working on the documentary "Rohna: Classified," which is set to premiere in November, coinciding with the 80th anniversary of the attack.

Ballo said it was common procedure to classify large war attacks, usually in an effort to sustain morale and to keep the enemy's successes under wraps. "The problem is after the war was over they never declassified," he said.

In speaking with historians, Ballo said the handful he's talked to believe the declassification process got lost in the shuffle, citing possible confusion between the U.S. War Department and the British War Office. Ballo isn't so sure.

"One thousand mothers would not let the War Department forget about the Rohna attack," he said.

Ballo and others blame a large number of the casualties on non-functioning lifeboats and inadequate lifebelts worn by the soldiers. But for years families were kept in the dark concerning the Rohna. "Most of the families of the casualties went to their own graves never knowing what happened to their son," he said.

A Staunton woman in her 90s reportedly also had a brother who died aboard the Rohna, but The News Leader was unsuccessful in contacting her despite several attempts.

Manning said not much is known about his cousin's short life or his death. "My mother said he was lost at sea, and that's the only thing she knew," he said.

Old newspaper clippings from Vermont initially stated Mainville was missing in action in the "North African area," and that his parents had received a letter from him just six days before the Rohna was sunk. According to the yellowing newspaper article, Mainville graduated from high school the year before he died and played varsity football. His father managed a local auto garage.

Manning, who has read the few books written about the Rohna's sinking, said thoughts about his cousin arise in earnest twice a year — around the anniversary of Mainville's death and on Memorial Day — and said he posts about him on social media.

"Doing my part a couple times a year," he said. "Just to keep it fresh."

Details surrounding the attack, hidden for decades, are disturbing.

Manning said the Rohna was part of a 24-ship convoy. On Nov. 26, 1943, it left Oran, Algiers, in North Africa and headed east in the Mediterranean Sea for a long stretch known as "Suicide Alley," a killing zone for German U-boats in the water and the German Luftwaffe from the air. The boat, a rundown cruise ship turned personnel carrier, had over 2,000 passengers. Manning said many soldiers would later note the Rohna looked "tired and rusty."

That same afternoon at about 2 p.m., Manning said soldiers aboard the Rohna heard gunfire, causing many of them to rush onto the boat's deck for a better view, while others opened portholes to peer into the sky to watch aerial dogfights between the German, French and American forces. Manning said the soldiers who went up above were ordered below deck.

Some of the enemy bombers were equipped with newly developed radio-controlled Henschel missiles, Manning said, and several were unsuccessfully deployed during the attack. However, late in the afternoon during a second wave of attacks, he said the Rohna was struck port side by one of the radio-controlled missiles, which exploded on impact in the engine room and blew an enormous hole in the opposite starboard wall.

An estimated 400 troops, either in the adjacent mess hall or in their bunks, immediately died, according to Manning. He said the concussion was so violent that it decapitated many of the soldiers who had been peeking through their port holes in an effort to watch the air battle.

Chaos reigned, Manning said. The ship's nearly two-dozen lifeboats were held in by rusted pins that had also been painted over, and he said crew members had to use axes and hammers but could only free about eight of the boats. Most of those capsized or filled with water once they hit the sea.

The soldiers had also been issued lifebelts, but Manning said they weren't instructed on how to use them properly. When activated, CO2 cartridges would inflate the belts, but Manning said because many of the soldiers were wearing the belts along their waist and not under their arms in the proper position, once they were in the water the belts made them top heavy and forced their heads underwater, drowning them.

Other soldiers who made the long leap into the sea from the the sinking Rohna were decapitated by the chinstrap to their helmet. Ropes that were used to lower others were too short and made slippery by blood, resulting in violent falls into the water, Manning said.

All the while, Manning said the sea was on fire because of all the burning petroleum seeping from the Rohna. To make matters worse, German planes returned to strafe the survivors as they bobbed at sea, he said.

The ship sunk in little over an hour.

There's no telling how Mainville died, but Manning said his cousin's room was right next to the engine room near the initial blast. "So, it's a very good chance he was disintegrated right on impact," he said. "You're hoping he didn't suffer, like in the ocean."

Like many others this Memorial Day weekend, Manning's thoughts will turn to those U.S. soldiers who have lost their lives defending our freedoms. More specifically, he'll remember the more than 1,000 troops who died along with his cousin.

"They were babies," he said.

Brad Zinn is the cops, courts and breaking news reporter at The News Leader. Have a news tip? Or something that needs investigating? You can email reporter Brad Zinn (he/him) at bzinn@newsleader.com. You can also follow him on Twitter.

This article originally appeared on Staunton News Leader: Augusta County man remembers cousin on Memorial Day