1,500 Black college students challenged police in 1961. The Supreme Court took their side.

USA TODAY’s “Seven Days of 1961” explores how sustained acts of resistance can bring about sweeping change. Throughout 1961, activists risked their lives to fight for voting rights and the integration of schools, businesses, public transit and libraries. Decades later, their work continues to shape debates over voting access, police brutality and equal rights for all.

BATON ROUGE, La. – Sylvia Copper, 20, stared at the police officer as he bounced a tear gas can in his hands.

It was 10 days before Christmas 1961. She stood outside the Baton Rouge courthouse with at least 1,500 other Black college students, protesting the arrests of 23 peers for picketing outside segregated stores the day before.

The air was cold, the ground damp from rain, and the officer seemed nervous as he fidgeted with the container until it slipped from his grasp.

The canister hit the ground and released a cloud of toxic fumes. Officers nearby reacted by throwing cans of their own, filling the air with chemicals that burned the eyes of anyone nearby.

The young people fled through a row of homes, knocking down fences “like cattle,” Copper said. They screamed as police gave chase, hitting students with nightsticks and placing some under arrest.

From jail cells atop the courthouse, those arrested the day prior watched in horror through small windows.

The officers, protesters said, wanted to make the students an example of what happened when Black people stepped out of line.

The violence soon proved to have the opposite effect.

The officers' response rallied more white Americans to support Black protesters and set the foundation for a Supreme Court case against bias in law enforcement. In 1965, the high court ruled protesters could not be punished for "peacefully expressing unpopular views" – affirming First Amendment rights for future generations.

“It created a precedent that you couldn’t just charge people with anything and put them away and expect those charges to stick,” said John Pierre, chancellor of the Southern University Law Center in Louisiana.

Ronnie Moore, a civil rights activist involved in the Baton Rouge demonstration, said if white police officers and lawmakers had not violently sought to stall progress, the work he and other protesters did likely would not have gained traction.

“The most effective strategy to kill the civil rights movement would be to never use dogs, never use water, ignore (protesters) and they’ll never make the headlines,” he said. "They never had the discipline to do that. They almost never had the ego to do that.”

‘The hope of the family’

The night before the demonstration, Copper called her mom from Southern University, a historic Black college overlooking the Mississippi River.

Her mother was a widow raising three children. She wanted to see her daughter earn her degree in nutrition, not go to jail. But on the phone, she said she understood her child’s pull to protest.

“We knew all along that Blacks weren’t getting what everybody else was getting,” Copper said. “It came to a point where everybody was just ready for a change.”

Many Southern University students grew up in the Deep South, accustomed to sitting at the back of public transit, being denied service at businesses and playing in streets instead of whites-only parks.

Their parents saved money to help their children attain the education they’d been denied. At church, they prayed for societal change.

But the students felt hard work and prayer could get them only so far. They had to pressure white people to treat them as equal citizens.

“Many of these folks could not afford to go to jail,” Pierre said. “The students couldn’t afford to be kicked out of school. Some were the hope of the family. They were put through hell to do something to not just be the generation that stood by and let white supremacy rule the day.”

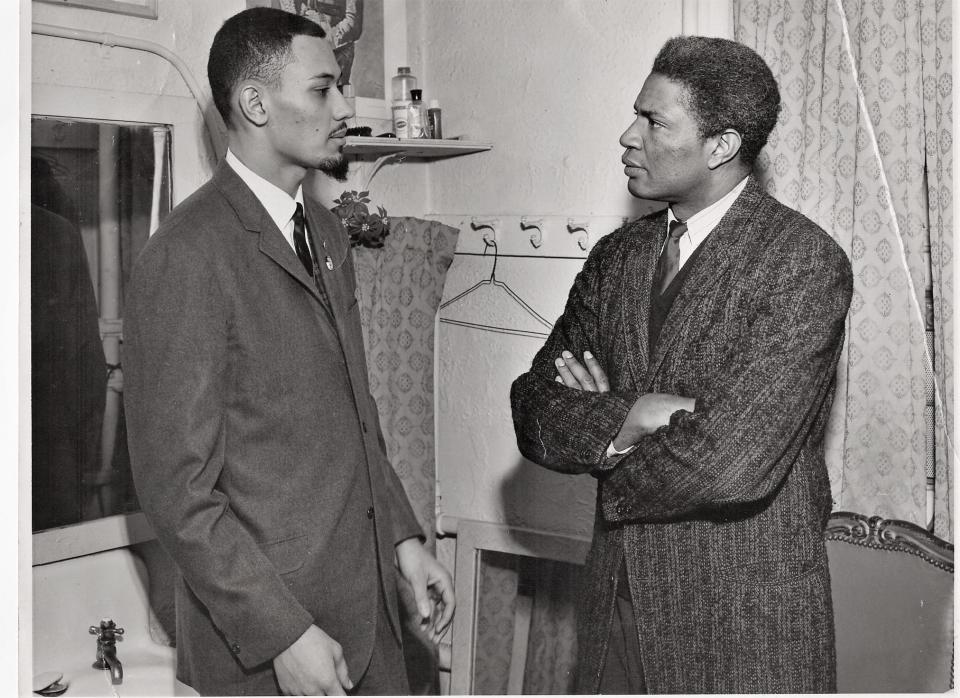

Early in the fall semester, students interested in protesting segregation began meeting at Camphor Memorial Methodist Church near campus. Members of the Congress of Racial Equality, a pivotal civil rights group, had come to help them organize. For months, they trained students on how to plan demonstrations and to protect themselves against violence.

“They would go through show-and-tells with us,” Copper said, “hitting at us and shouting at us, spitting in our face. They would tell us to, say, if they try to hurt or kick you or beat you down, roll yourself up so you can kind of protect yourself, your face, your head, your backs.”

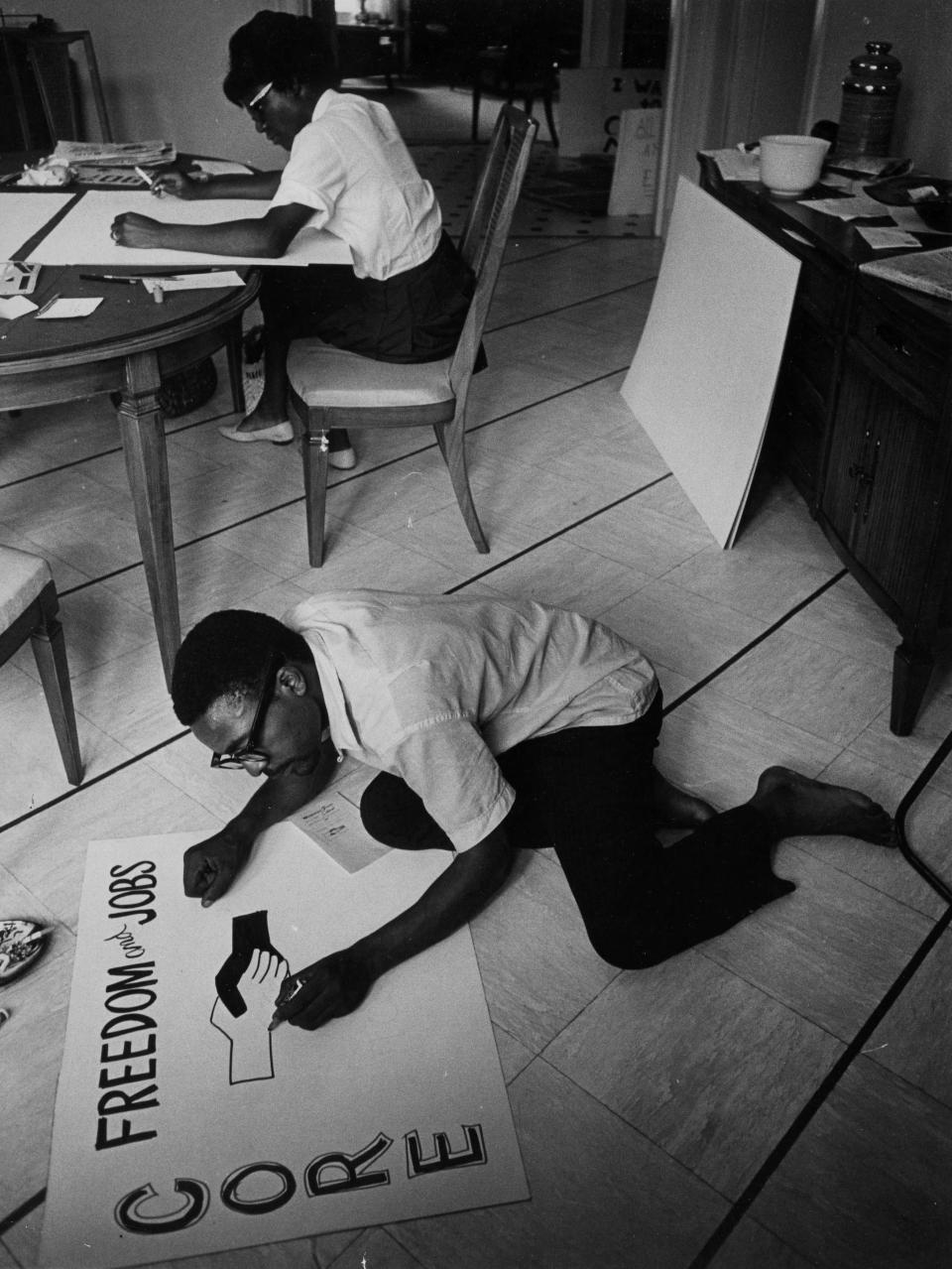

As the holiday season began, CORE sent letters to a dozen department stores, asking them to provide equal employment for Black workers and to open all facilities to Black customers.

In early December, CORE escalated its demands. Activists called on Black shoppers to boycott the retailers. They performed sit-ins at white lunch counters and picketed stores that refused to desegregate.

“At some point, we made the decision that in order to dramatize how terrible the system is and how much change is needed, we’re going to have to decide to go to jail over the Christmas holidays,” said Weldon Rougeau, then a 19-year-old sophomore at Southern University and vice chair of CORE in Baton Rouge.

Rougeau grew up in rural Louisiana, the only child of tenant farmers who were forced to share profits with the property’s owners. The arrangement never felt right to him. Rougeau, like many young people, joined the civil rights demonstrations unfolding across the nation.

“I can’t begin to tell you the consternation that caused in households of many of the students, including my parents,” he said. “People were well aware of all the terrible things that had happened to Black people who were arrested, some of whom were never found again.”

A 7-mile walk for civil rights

Baton Rouge officials had had enough.

For days, the students had disrupted life in the predominantly white business district.

District Attorney Sargent Pitcher issued a warning: Anyone caught picketing would be arrested and “fully prosecuted.”

CORE members were ready for the risk. On Dec. 14, nearly two dozen met downtown to protest again.

Each carried signs to their destinations: “We tried to talk – now we walk.” “This store discriminates – don’t buy here.”

Most didn’t make it to the storefronts.

“They stopped me after about 25 steps or so,” said Joe L. Smith, then sophomore class president at Southern University. "It didn’t take five minutes for me to get arrested.”

In total, 23 protesters were handcuffed and taken to jail.

Moore, chairman of CORE in Baton Rouge, quickly prepared students for the second phase of their plan.

On Dec. 15, they'd rally for the picketers’ release.

Students were supposed to travel to the courthouse by bus.

In the chilly morning hours, they met at a railroad track near the edge of campus in Scotlandville, a majority Black community in northern Baton Rouge.

Dozens piled into buses helmed by Black residents. But police soon intercepted them. Officers claimed the buses were overloaded, Moore said, and placed the drivers under arrest.

At the front of the crowd, Moore rode in a car with loudspeakers. His job was to keep the line moving to the courthouse. But as the car left the safety of campus, officers handcuffed him for using a sound truck without a permit. They later added a charge of conspiracy to commit criminal mischief with a $2,000 bond – equivalent to $8,000 today.

The students had a choice: Give up or walk 7 miles from the university to the rally site.

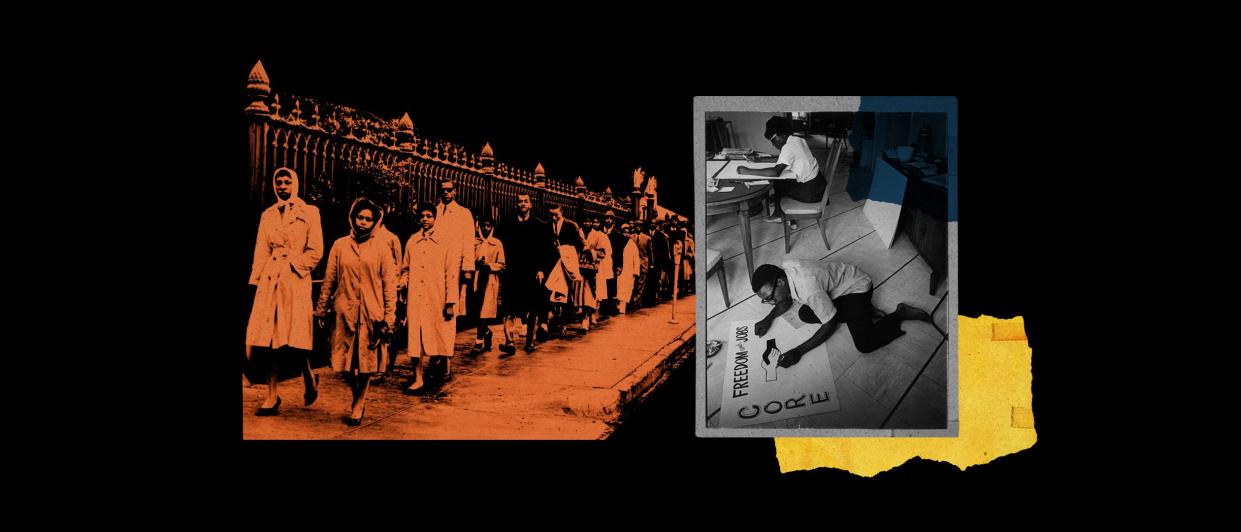

CORE captains organized hundreds of students into orderly lines and began the trek on foot. A light rain fell as they walked quietly on the shoulder of Scenic Highway, a major state thoroughfare. Soon, white drivers aimed their tires at puddles as they passed, splashing water onto the students’ best dresses, suits and coats.

Hours later, the protesters turned onto St. Louis Street, filling a sidewalk across from the courthouse and jail.

The Rev. Benjamin Elton Cox, a CORE field secretary, had assumed leadership following Moore’s arrest. He informed police Chief Wingate White of the protesters’ agenda.

“We intended to sing one stanza of ‘God Bless America,’ recite the Lord’s Prayer and make allegiance to the flag,” Cox later testified.

‘Move them out’

Cox, who earlier that year volunteered to be one of the original 13 Freedom Riders challenging segregation in interstate travel, had spent weeks in Baton Rouge helping students organize.

On Dec. 15, he stood between them and more than 300 police officers armed with tear gas, revolvers and submachine guns.

Don’t feel intimidated, Cox told the students.

“If they give us tear gas, we will take it and fall honorably," he said, according to news reports.

The students proceeded to sing, their voices carrying to the jail on the courthouse’s fourth floor.

From their cells, arrested students and CORE members banged on windows and cheered in response.

“It was very inspiring,” Rougeau recalled. “It said, ‘Hey, we have not been forgotten.’”

White witnesses, in court documents, described the scene differently. The students “cheered in a conquest type of tone,” police Capt. L.C. Font said. Officers said they didn’t know what the students might pull out from under their coats. They feared the crowd might attempt to overtake the jail.

Tensions began to rise. Cox addressed the crowd.

“It is lunchtime,” he told the activists. “Let us go downtown to eat.”

He pointed the students to businesses CORE had been picketing.

“These stores are open to the public. You are members of the public," he said. "Go to the designated places and sit until you are waited on.”

Sheriff Bryan Clemmons wasn’t about to let that happen. “We have given you the opportunity to demonstrate here," he said through a loudspeaker, "but now you are creating a disturbance.”

He turned to his deputies: “Move them out.”

The students ran, stopping only to turn on a hose and wash the tear gas from their eyes.

Some headed for stores on Third Street, where police released two German shepherds. The animals bit at the activists, tearing their flesh and clothes.

By the end of the day, 300 sought treatment at the university infirmary.

Fifty more students and CORE members were arrested, including Cox. All were transported to the same jail they’d just protested.

Christmas behind bars

Moore spent Christmas, New Year’s Day and his 21st birthday behind bars.

The 73 protesters arrested owed a combined $116,000 in bail. As their attorneys and families worked to raise the capital, the protesters remained in a poorly ventilated jail cell meant to hold 48.

Moore was briefly released in January and returned to Southern University, where he and eight other students were expelled for their roles in the protest at the order of an all-white Board of Education.

Moore and Rougeau were quickly arrested again for trespassing on campus. This time, they were charged with criminal anarchy or attempting to overthrow the state government.

For more than 50 days, the pair was held in solitary confinement without bond. The 6-by-9-foot cell they shared had a bunk bed, sink and toilet and no windows. They couldn’t receive visitors other than their lawyers. They were allowed out to shower once a week.

“I remember the isolation and really the sense of almost hopelessness,” Rougeau said.

Some CORE members had worried the police attack would scare off future protesters and strangle the fledgling movement.

But in the days after the protest, more demonstrations popped up on campus and in New Orleans, with young people demanding to know why the students were being punished.

In January 1962, The Campus-Times at the University of Rochester sent a reporter to Baton Rouge to learn how students at the northern school could help.

And that spring, former first lady Eleanor Roosevelt led an inquiry into the treatment of civil rights activists, inviting four Louisiana protesters to testify before a committee. The group later called on the president, Congress and Department of Justice to better protect demonstrators.

“That was also a major turning point for the movement, especially outside of Louisiana,” Rougeau said. “People began to see what the state was doing to these students, trying to express their constitutional rights.”

Fear ‘cannot alone justify suppression’

In early 1962, Cox returned to the courthouse to face trial in a segregated courtroom.

Judge Fred A. Blanche Jr. had been in the building during the 1961 protest. Though he didn’t step outside to witness the crowd, he said in his ruling he “felt apprehensive that trouble or violence could erupt from such a situation.”

He found the CORE field secretary guilty on three misdemeanor charges: obstructing the sidewalk, obstructing justice and disturbing the peace. He sentenced Cox to serve one year in jail.

Attorneys for the reverend appealed, arguing police officials’ “fear of serious injury cannot alone justify suppression of free speech.”

But the Louisiana Supreme Court stood firm on the ruling, depicting the students as “well-trained and indoctrinated and subject to any desired activity required by Cox by so simple a signal as the snapping of his fingers.”

As the civil rights movement gained momentum, CORE attorneys continued to fight the charges with the hope of setting a precedent for protests to come.

In 1965, their prayers were answered when the U.S. Supreme Court overturned the lower court’s verdict. At the crux of the judges’ decision was a video from the rally that showed Cox and the students protesting peacefully.

To uphold Cox’s charges would mean allowing “persons to be punished merely for peacefully expressing unpopular views,” Justice Arthur Goldberg wrote in the majority opinion.

Decades later, lawmakers are once again targeting freedom fighters in the wake of the murder of George Floyd and the global Black Lives Matter protests that broke out after his death in May 2020. A spate of state laws proposed this year would give law enforcement broad discretion to suppress demonstrations, said Nicholas Robinson, a senior legal advisor for the International Center for Not-for-Profit Law.

"There's always going to be another way to deter protesters, to undercut their rights to assemble," said Ada Goodly, director of the Lewis A. Berry Institute for Civil Rights and Justice at Southern University.

Copper, now 80 and a legislative researcher for the state of Louisiana, said such anti-protest laws are exactly why people need to keep fighting. Black people do not have the same opportunities to build wealth as white people, and lawmakers continue to file bills making it harder for Black residents to vote, she said.

“People are still in denial. They don’t think they’re prejudiced. They think they’re doing alright. They think Black people are alright,” she said. “We’re still in the same rut that we’ve been in all along.”

To report these stories, USA TODAY interviewed veterans of the civil rights movement, historians and witnesses and reviewed public records.

Explore the series

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: How Louisiana students fought segregation and secured protest rights