10 Images That Explain What to Expect From Climate Change

Although carbon emissions in early 2020 plunged thanks to COVID-related lockdowns around the world, they rebounded quite quickly. As we near the end of 2021, many economies are starting to see carbon emissions climb to levels close to or even higher than pre-pandemic averages.

The damage of greenhouse gas accumulation in the atmosphere cannot be reversed overnight. Some things are sure to get worse: The world will get hotter, the glaciers will continue to melt a bit, sea levels will rise, storm events will hit us harder, and people will suffer.

And yet there were still signs of hope this year that solutions to climate change were on the horizon. COP26, the UN climate change conference originally slated for 2020 before the pandemic pushed it back to this past November, led to some surprisingly optimistic agreements from world leaders to reduce carbon emissions and work together to expand programs that would move national economies toward renewable energies. It also provided new frameworks for building resilient infrastructure to mitigate the effects of climate, provide more resources to developing countries, and invest in more radical innovations rarely taken seriously in years past.

Climate change in 2022 doesn’t exactly look bright, but it does have bright spots. Here are 10 images that explain what we can look forward to—and what we ought to prepare for.

Conceptual art for JPSS-2, which will orbit around both of the planet's poles.

Four New NASA Earth Science Missions

NASA’s Earth Science program under Donald Trump was defined by spending cuts and mission cancellations. The Biden administration is looking to reverse those trends quickly and beef up the fleet of satellites the agency uses to monitor climate changes across the globe.

Next year will see the launch of four new missions into orbit: TROPICS, a six-satellite project to help scientists measure tropical cyclones and understand how a hotter climate is making storm events worse; EMIT, an instrument that will track the interactions of mineral dust on the climate from the International Space Station; JPSS-2, a satellite designed to help experts predict extreme weather events like storms, wildfires, and even volcano eruptions; and SWOT, which will study the world’s oceans and teach us how surface waters encourage and mitigate climate change.

The ivory-billed woodpecker officially went extinct this year.

Biodiversity

We’re well aware that climate change is making it harder for the world’s plants and animals to thrive. But in the grand scheme of the potential disasters climate change could bring, this hasn’t been a high priority for many policymakers. After all, it’s difficult to say we should save the polar bears when there are humans whose homes are being destroyed by floods every year.

In the distant future, 2021 and 2022 could be seen as a turning point for understanding how dependent people are on seeing biodiversity thrive on this planet. We need natural pollinators like bees to grow our crops, robust wetlands to keep our freshwater sources clean and plentiful, and a working food web that can enable us to use forests as a natural sink for excess carbon. And scientists have finally begun to start engaging policymakers directly on these issues.

The UN Biodiversity Conference from April 25 to May 8 next year in Kunming, China, will be critical in getting nations to commit to keeping the 8 million plant and animal species on this planet from going extinct.

Climeworks’ carbon capture facility at Hellisheiði Geothermal Power Plant in Iceland.

Carbon Capture

Perhaps no issue better illustrates how much more alarming climate change has become over the last decade than the change in perception over carbon capture technologies. Just a decade ago, most leading experts scoffed at the idea that we should suck out carbon dioxide emissions and store them underground where they can’t do any harm. It seemed thoroughly outlandish.

In 2021, the world is embracing carbon capture. Elon Musk said he would donate $100 million as a prize for proving out carbon capture technologies. China’s largest carbon capture and storage plant was finished in January. The world’s first commercial carbon capture facility opened up in Iceland in September.

Why the change? Simply put, the world fumbled its efforts to really make a significant dent in carbon emissions. Radical technologies like carbon capture are now a necessary part of the equation. Expect carbon capture to make an even bigger splash in 2022.

Rainfall from Hurricane Ida floods the basement of a Kennedy Fried Chicken fast food restaurant on Sept. 1, 2021 in The Bronx, New York City.

Floods, Floods, Floods

It was a catastrophic year for flooding events. More than 300 people died in China’s Hainan province in July when a year’s worth of rainfall slammed into the region over the course of three days. A similar situation unfolded in Central Europe, leading to the deaths of more than 180 people. Hurricane Ida hit the U.S. gulf states and killed nearly 100. The storm’s remnants also managed to wallop New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania, leading to historic floods throughout city centers. In November, South Sudan was overrun by the worst floods experienced in over half a century.

As sea levels rise and storm events become more frequent and more devastating, similar events are expected to hit the world throughout 2022.

Russian startup L-Charge began expanding its mobile charge stations for electric vehicles into new countries this year. This station is in Barcelona, Spain.

Electrification

The Biden administration was banking on implementing huge incentives for electric vehicle (EV) growth through the Build Back Better legislation. West Virginia Sen. Joe Manchin’s withdrawal of support for the bill threatens to sink those initiatives, but regardless of whether the two groups can come to some sort of agreement, EVs will become a bigger deal in 2022. EV sales in 2021 in Europe grew by 157 percent; in China, by almost 200 percent; in the U.S. by 166 percent. Electric scooter sales doubled in the U.S. Charge stations are proliferating as more people are buying into electric vehicles—even in poorer countries. Public transportation systems are increasingly converting to electric power. No matter what the U.S. government does, the electric vehicle market is not going to slow down in 2022.

The Drum Tower in Beijing, China on March 15, 2021, as a sandstorm pummels the city.

Desertification

If you were in Beijing in March, you might have thought the world was ending, as the sky turned orange and the city was hit with the worst sandstorm in 10 years. This was a consequence of desertification, propelled by the loss of trees and plant life that would otherwise provide stability to soil and keep dirt in its place.

China isn’t the only place to experience the harsh consequences of desertification. In India. 29.7 percent of the land has degraded. The UAE and other Gulf states are watching the land literally dry up and foment more frequent sandstorms. African nations are spearheading an ambitious project called the Great Green Wall to keep the continent’s savannahs from turning into a desert, but they have only met 4 percent of their goal. So 2021 may have just been a taste of what to expect from desertification in 2022.

Gille Dreyfus poses in front of the vertical farming system built by his French start-up, Jungle, located in Paris.

Vertical Farming

While so much farmland around the world erodes into an unsuitable environment for growing crops, some food producers are starting to move indoors into temperature-controlled warehouses. Vertical farming is set to have a banner year in 2022, with an explosion of startups in the U.S. banking on more investment from local governments and an expansion of their footprints. Major companies like Infarm are planning to set up farming facilities in more countries in Europe and North America. New York-based Gotham Greens expanded into 800 more retail stores in just 2021 alone—this number is expected to balloon over the course of the next year. As we wrote earlier this year, the fact that vertical farming can avoid the current supply chain obstacles plaguing so many other industries means it’s expected to grow tremendously over the course of the next year.

Downtown Austin on February 15, 2021, after a trashed the region and brought historic levels of snow and cold temperatures to the state.

Inexplicable Winters

It wasn’t immediately clear that the February cold snap that hit Texas and killed 125 people was caused by climate change. Then in September, a new study published in Science made the link more explicit, suggesting that changes in the polar vortex caused by climate change helped contribute to the severe weather storm crippled power and water around the state for millions. February highlighted the fact that climate change doesn’t just hit us with hotter summers and harsher hurricanes—and if we don’t have the type of infrastructure in place that is resilient to different kinds of conditions, we can expect to see the same kind of suffering almost annually.

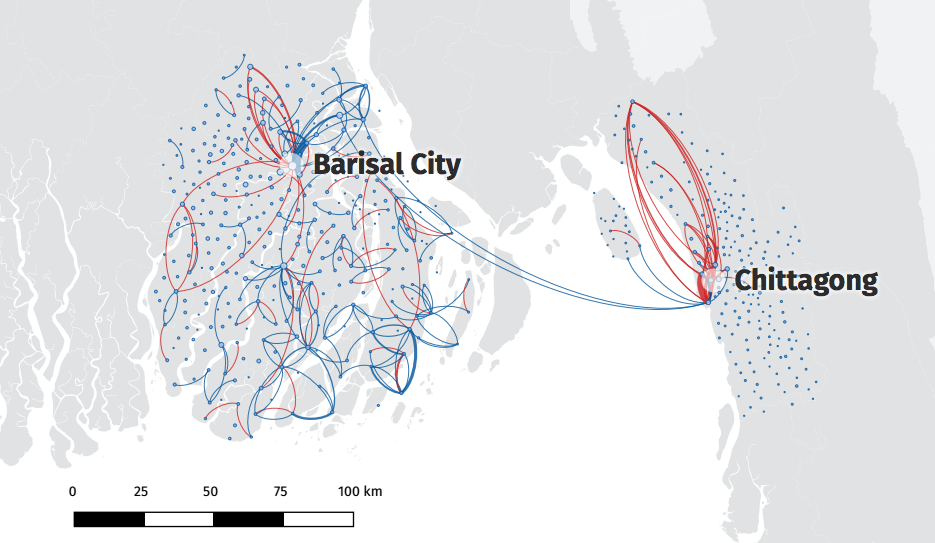

Mobile network data from 2013 shows how people in Bangladesh were migrating to safer spots as Cyclone Mahasen made landfall near Barisal City. Data like this could help us better understand how to plan for future disaster mitigation efforts during severe storms.

Big Data

The data revolution has swept across nearly every major industry at this point. As the world’s government and the commercial sector pour more money into researching climate change, big data will play a critical role in helping us understand what is going on both at a macro scale across the globe, as well as a micro-scale on the ground. Major tech companies like Google are already finding ways to leverage the massive amounts of mobile phone data they collect and harness it as part of climate initiatives.

The big question, of course, is whether these companies can be trusted to use this data responsibly. 2022 will be the year this question is more openly discussed in the public forum.

A firefighter at work as the Caldor Fire burns in Grizzly Flats, California on August 22.

Boiling Temperatures

Lastly, we can expect the world to get hotter—duh. There were droughts in the American Southwest, record heat waves in North America (including an absolutely insane 116 degree Fahrenheit high in Portland, Oregon, that was literally melting the highway), and wildfires raging through California through the late summer. Around the world, Chile trudged through another year of its decade-long megadrought, and Brazil had its driest summer in a century. The glaciers continued to melt, and Switzerland went as far as to lay out protective blankets on one of its mountains to protect what little ice remained.

None of this is going to get fixed any time soon. Plenty of people are looking for better ways to keep us cool in our homes, and you can expect these innovations to get more attention in the coming year.

Got a tip? Send it to The Daily Beast here

Get our top stories in your inbox every day. Sign up now!

Daily Beast Membership: Beast Inside goes deeper on the stories that matter to you. Learn more.