10 NC Black history lessons you likely weren’t taught in school (but should have been)

The push to teach Black history to North Carolina school students for more than just one month out of the year is getting fresh attention, thanks to newly adopted state social studies standards requiring teachers to include issues of racism and discrimination in their lessons, as well as perspectives of marginalized groups.

What should a curriculum that includes important aspects of African American history in North Carolina look like? Will it go beyond the Greensboro lunch counter sit-ins to include the Wilmington Massacre of 1898? As we celebrate the accomplishments of thriving Black business districts, shouldn’t we also learn about the discrimination behind the Jim Crow laws that made them a necessity?

This is by no means a complete list of North Carolina’s Black history, but it is a starting point to learn more.

Black-owned business districts/Black Wall Street

Dates: Late 1800s through mid 1900s.

Synopsis: Black-owned business districts developed in cities and towns across the nation during the Jim Crow “separate but equal” era, when Black citizens were not welcome to dine or do business in many white-owned establishments. Typically situated in a concentrated section of a town or city’s downtown area, these Black-owned businesses thrived, some growing to remarkable size and influence. The most prominent Black business district in North Carolina — and one of the most prominent in the country — was Durham’s Black Wall Street, located on Parrish Street downtown.

Key people and things: The center of Black commerce in Durham originated in the Hayti District, but expanded when Mechanics and Farmers Bank and North Carolina Mutual life insurance company opened on Parrish Street. M&F Bank, established by a group of seven African American businessmen, is one of the first African American-owned banks in the U.S., and is largely responsible for bolstering the Black community in and around Durham. NC Mutual, founded by John Merrick and Aaron McDuffie Ward and later expanded by Charles Spaulding, was at one point considered the world’s largest African American business, with all three men gaining national acclaim.

Impact: Black-owned business districts were incredibly important to their communities, but Durham’s Black Wall Street distinguished itself from most other Black business districts across the U.S. because of its prominent financial institutions, which helped provide the infrastructure for other Black businesses and Black citizens to prosper. North Carolina Mutual and Mechanics & Farmers Bank are still in business today.

What happened: The downfall of these districts was largely a result of both desegregation and urban renewal — Black citizens were not as reliant on Black-owned businesses as segregation ended, and businesses of all types started leaving downtown areas for shopping centers. In some cases, “revitalization” campaigns resulted in the demolition of older businesses to make way for newer construction. In Durham, the construction of the Durham Freeway contributed to the demise of thriving Black commerce in the city.

Beyond Durham: Black business districts existed in most North Carolina cities, including Raleigh, Greensboro, Charlotte, Wilmington, Asheville and Burlington. Outside of North Carolina, the Greenwood District in Tulsa, Oklahoma, had its own Black Wall Street, and by 1920, was considered the wealthiest Black community in the United States. A race riot in Greenwood in 1921, perpetrated by the white citizens of the city against the Black citizens, is considered one of the worst incidents of racial violence in American history. Black businesses were destroyed, nearly 7,000 people were injured and 10,000 Black citizens left homeless. Estimates of those left dead range from 75 to 300.

Interesting fact: Durham’s Black Wall Street, along with plentiful jobs in Durham’s tobacco factories, is credited as one reason Durham had one of the strongest Black Middle Class populations in the nation.

To learn more

Watch: Stanley Nelson’s 2019 documentary “Boss: Black Business in America” is an excellent look at African American entrepreneurship, and includes the history of Durham’s Black business district. Available through PBS: pbs.org/wnet/boss.

The Wilmington Massacre of 1898

Date: Nov. 10, 1898, after months of race-baiting speeches and newspaper editorials.

Synopsis: A generation after the Civil War, white-supremacist Democrats chafed at Black suffrage and the elevation of Black people to elected office. Wilmington, North Carolina’s largest city at the time and majority Black, had a Fusionist government built from an alliance of Blacks and poor whites. For months leading up to the November 1898 election, powerful state Democrats — including News & Observer publisher Josephus Daniels, former Congressman Alfred Waddell and developer and businessman Hugh MacRae — used speeches, pamphlets, newspaper cartoons and editorials to stir up fear and anger against Blacks and to discourage them from coming to the polls. On Nov. 10, the day after the election, organizers led an armed white-supremacist mob into Black neighborhoods and businesses, killing between 60 and 300 Black residents. They torched property, sent thousands of people into hiding, then replaced Blacks serving in local leadership positions with more conservative whites.

Key person: Alexander Manly, owner of Wilmington’s Black newspaper, The Daily Record, who had pushed back in print against the racist campaign.

Impact: Incorrectly portrayed for decades as the white suppression of a Black uprising, the Wilmington Massacre, also known as the Wilmington Insurrection, remains the only successful coup against an elected government in U.S. history. It helped usher in additional disenfranchisement of Blacks in Wilmington and across the state, including the proliferation of Jim Crow laws and state-sanctioned segregation. As recently as 2020, a federal judge found that North Carolina still appeared to be trying to suppress Blacks from voting.

Interesting fact: A lynching party set out in search of Alexander Manly the night of Nov. 9, 1898, but were met by about 200 armed Black people when they arrived at Manly’s newspaper office. Manly and his partner-brother, Frank, fled the city. The mob destroyed the printing press and burned the office building to the ground. Alexander Manley later settled in Philadelphia and helped found The Armstrong Association, which later merged with the Urban League of Philadelphia and helped a generation of African Americans migrating from the South find jobs and housing.

To learn more

Read: The News & Observer published a special section on the 100th anniversary off the massacre, “The Ghosts of 1898,’ which is available as a PDF (media2.newsobserver.com/content/media/2010/5/3/ghostsof1898.pdf).

Read: New York Times staff writer and book author David Zucchino wrote a book about the insurrection, “Wilmington’s Lie,” published in 2020.

North Carolina Black trailblazers

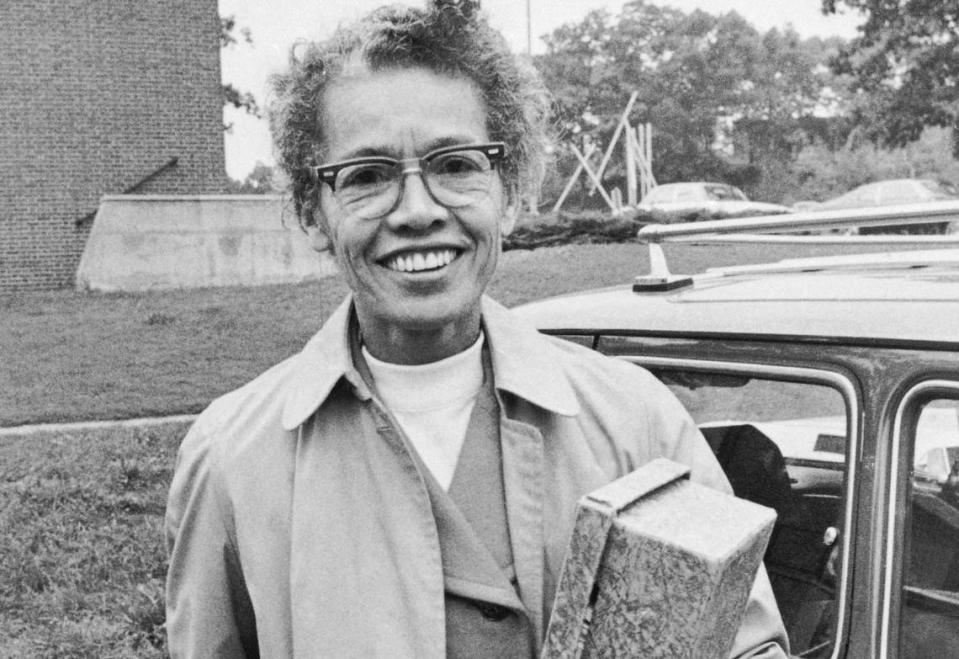

Synopsis: Pauli Murray grew up in Durham, an orphan raised by her aunt and grandparents, but she impacted the lives of Black people and women across the nation. As a young college graduate seeking to attend graduate school, Murray was denied entry to the University of North Carolina because of her race and later denied entry to Harvard because of her gender. Fueled by the injustices of Jim Crow (and what she termed “Jane Crow”) rules, Murray earned advanced degrees from Howard and Berkeley, and became the first African American to earn a doctorate of jurisprudence at Yale University.

Murray worked or had friendships with Langston Hughes, W.E.B. DuBois, Eleanor Roosevelt, Thurgood Marshall, John F. Kennedy, Betty Friedan and Ruth Bader Ginsberg. She was arrested — before Rosa Parks — for refusing to move to the back of a bus traveling from New York City to Durham. She helped launch the National Organization for Women. Murray at different times in her life identified as a man and as a woman, but used the pronoun she in her autobiography. Later in life, she became an Episcopal priest — the first African American woman to be vested as an Episcopal priest. The Episcopal Church bestowed sainthood on Murray in 2012.

The Durham childhood home of Murray, who died in 1985 at the age of 75, is a designated National Historic Landmark by the Department of the Interior.

Other important firsts: In North Carolina, a study of African American “firsts” would be incomplete without considering:

▪ Harriet Jacobs, who was born in Edenton and escaped slavery to go on to write one of the first narratives about the struggle for freedom by female slaves.

▪ St. Agnes Hospital, a hospital on the grounds of St. Augustine’s University from 1896 to 1961, housing the first nursing school in the state for African Americans and known for a while as the best hospital for Blacks between Washington and New Orleans.

▪ Judge Henry Frye, the first African American chief justice of the North Carolina Supreme Court (and one of the first Black U.S. Attorneys in the South).

▪ Walter “Buck” Leonard, who grew up in Greensboro and became one of the first African American baseball greats (called “the Black Lou Gehrig”).

▪ Julius Chambers, a civil rights icon who was the University of North Carolina School of Law review’s first Black editor-in-chief.

▪ John Baker, the first African American sheriff in North Carolina after Reconstruction, serving Wake County for almost 24 years.

To learn more

▪ Watch: When it’s more widely available, the documentary “My Name is Pauli Murray,” directed by Betsy West and Julie Cohen (debuted at the Sundance Film Festival in January 2021).

▪ Read: “The Firebrand and the First Lady” by Patricia Bell-Scott.

▪ Read: “Jane Crow: The Life of Pauli Murray” by Rosalind Rosenberg.

Freedmen’s settlements in North Carolina

Date: Began during the Civil War

Synopsis: During and after the Civil War, more than 360,000 African Americans living in North Carolina were freed from slavery. Some left the state to search for work or family or to apply for a land grant in western states under the federal Homestead Act. But most remained in the state to start new lives as free people. Where whites would sell, often on land undesirable for farming, African Americans began buying property and developing freedmen’s villages.

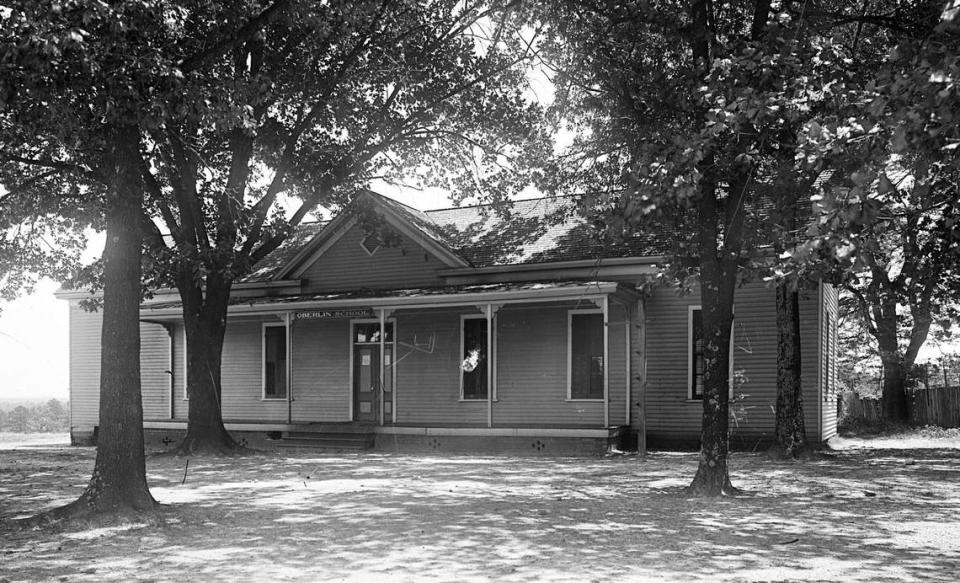

Key places: Black people migrating into Raleigh after the war established at least 13 freedmen’s communities, including Method, in southwest Raleigh, St. Petersburg and Hungry Neck, both near the N.C. State Fairgrounds, along with Brooklyn, Lincolnville and Oberlin Village. Not all residents could afford to build homes, and many rented. Other significant freedmen’s villages in North Carolina include: James City, outside New Bern; Roanoke Island and Princeville.

Impact: Freedmen’s villages provided places for African Americans to live and thrive. They could build and own homes and start businesses, churches and schools at a time when white institutions would not assimilate them.

Related: A Black farmer from North Carolina named Timothy Pigford filed a class-action lawsuit against the federal government claiming the U.S. Department of Agriculture had systematically kept black farmers from getting loans and crop-disaster payments routinely given to white farmers. The USDA acknowledged the discrimination, which contributed to Black farmers losing about 90% of the land they owned during the 20th century. In 2010, Congress approved a settlement of $1.25 billion for thousands of farmers. It was one of the largest civil rights legal victories in U.S. history.

Interesting fact: While not all free Black people who migrated to Raleigh could afford to launch businesses, they dominated some industries. In 1891, all but two of the city’s 22 barbers were Black. By 1925, with the advent of Jim Crow laws and social segregation, the percentage would drop to one half.

The Greensboro Woolworth sit-ins/The struggle for civil rights

Date: Feb. 1, 1960

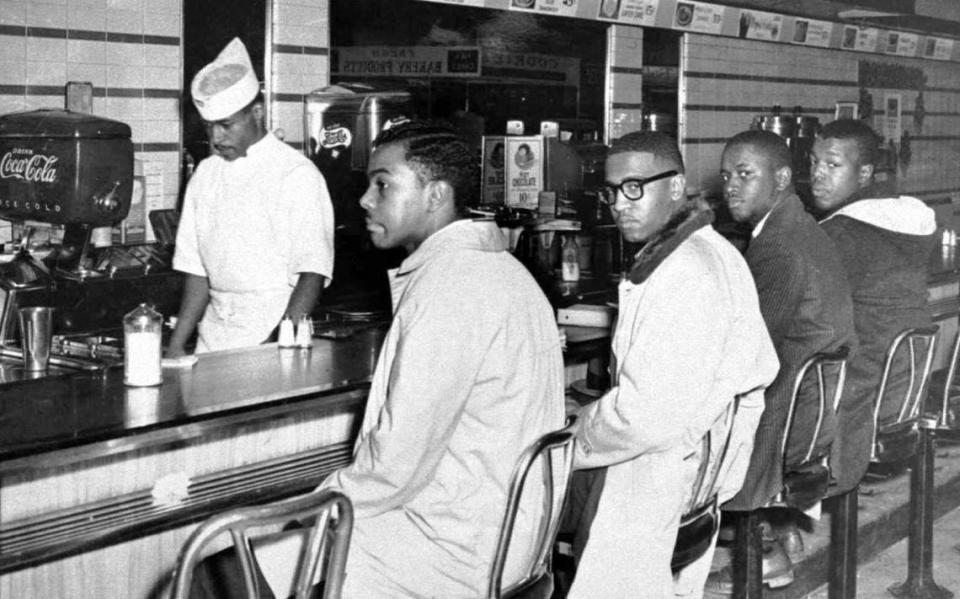

Synopsis: The struggle for fair and equal treatment of Black people in the United States, highlighted by the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and ‘60s that resulted in the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, made its gains through thousands of grassroots efforts across the country. One of the most significant of those was the lunch counter sit-in at the Greensboro F.W. Woolworth store. Four Black students from nearby N.C. A&T State University bought items at the downtown store and then took seats at the whites-only lunch counter. Their requests for service were ignored, and the manager closed the story early. They returned the next day with more students and continued to come back with growing support of churches and community members until Woolworth changed its policy and began serving Black people in July 1960.

Key people and things: A&T students Ezell Blair Jr., David Richmond, Franklin McCain and Joseph McNeil. Ella Baker, who held a meeting at Shaw University after the sit-ins and from that launched the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, or SNCC.

Impact: News stories about the Greensboro sit-in drew attention to the injustice of Jim Crow laws that kept Blacks from using libraries, parks, swimming pools, theaters and even water fountains in the same way as whites. By appealing to students, sit-ins drew young people into the Civil Rights movement, including through the SNCC. They also demonstrated the power of non-violent resistance to institutionalized oppression. The Greensboro sit-ins drew the most attention, but there had been a similar event at Royal Ice Cream in Durham in June 1957. And there would be others in Winston-Salem, Charlotte, Concord, Elizabeth City, Henderson, Raleigh, Salisbury, Shelby, Chapel Hill, New Bern and Wilmington.

Related: Freedom riders’ “Journey of Reconciliation” by bus in 1947 included stops in North Carolina to challenge segregation of interstate transportation.

Interesting fact: On Nov. 27, 1962, the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. gave a speech in the gym at Booker T. Washington High School in Rocky Mount. About 1,800 people heard him pronounce, “I have a dream,” which he would recite again at the March on Washington in August 1963. King had planned to give a different speech for the 250,000 people in Washington until gospel singer Mahalia Jackson called from the audience, “Tell them about the dream, Martin.” A recording of the Rocky Mount speech can be heard here. (www.ncpedia.org/martin-luther-king-jr-speech-rocky-mount-1962)

To learn more

Visit: The Woolworth store where the sit-ins took place closed as a retail operation in 1993 and now houses the International Civil Rights Center and Museum. Four stools from the lunch counter are at the National Museum of American History, part of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C.

The Green Book in North Carolina

Dates: 1936-1967

Synopsis: “The Negro Motorist (or Travelers’) Green Book” was a guide for Black Americans to travel safely through the country during the Jim Crow era. In the 1930s, automobile travel was more popular than ever, but Jim Crow “separate but equal” laws meant Black citizens couldn’t always patronize white businesses. Black travelers used these Green Books to know where they could safely eat and sleep, and which “Sundown Towns” (dangerous towns that banned Black people after dark) to avoid.

Key person: Victor H. Green, a Harlem-based postal carrier, started the Green Book in New York in 1937.

In North Carolina: North Carolina had 327 of these restaurants, hotels, barber shops, cab companies and sometimes even amenable homeowners listed in the Green Book, according to a 2017 research project by the NC African American Heritage Commission. The online database provided by the NC AAHC unsurprisingly shows there were many options available in larger towns like Raleigh, Durham, Greensboro and Charlotte, but none in the more rural counties. In Durham in the late 1940s and early 1950s, a Black traveler could eat at Jack’s Grill on Fayetteville Street, and then spend the night at Mrs. Mary Sims’ “tourist home,” just a few blocks away. In Raleigh, a motorist could have a drink at the Savoy on South Blount Street and then bed down at the Lightner Arcade and Hotel on East Hargett. In Charlotte, the old Biddleville Luncheonette is now the site of a Charlotte-Mecklenburg Police Department Metro Division.

Impact: Green Books were not only helpful for Black-owned businesses and absolutely vital for the safety of Black travelers, Smithsonian Magazine notes that they also offer historians a record of “the rise of the Black middle class, and in particular, the entrepreneurship of Black women.”

Interesting fact: The critically acclaimed 2020 HBO series “Lovecraft Country” has a major plot point involving the “Travel Book,” which is a travel guide for Black motorists based on the Green Book. The 2018 movie “Green Book,” while an Oscar-winner, was controversial because of its focus on the white character in the story and for relying on the “White Savior” and “Magical Negro” tropes.

To learn more

Watch: Opt for the 2019 documentary, “Green Book: A Guide to Freedom,” over the dramatic film. The documentary premiered on the Smithsonian Channel and is available to stream online.

Read: “Driving While Black: African American Travel and the Road to Civil Rights” by Gretchen Sorin.

Read: “Sundown Towns: A Hidden Dimension of American Racism” by James W. Loewen.

Black North Carolinians in music and arts

Synopsis: The world knew her as Nina Simone, but North Carolina first knew her as Eunice Kathleen Waymon, born in Tryon on February 21, 1933. Eunice showed a gift for the piano at an early age, and dreamed of becoming a concert pianist. She spent the summer of 1950 at Julliard (paid for with money raised by her community), but was denied entry to the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia. (She suspected it was because of her race.) Her shift from classical to popular music was purely one of financial necessity, and she took the stage name Nina Simone to hide her work in nightclubs from her Methodist minister mother. She released her first album, “Little Blue Girl,” in 1958, and her life changed forever. She performed everywhere from the Apollo Theater to “The Ed Sullivan Show” to Carnegie Hall. She came to be called “the High Priestess of Soul,” but her music drew from many styles, including classical, jazz, blues, gospel and popular music, and covering every genre from protest songs to romantic pop standards and Broadway tunes.

Impact: Simone wasn’t merely popular, her music had purpose. Her songwriting in the 1960s conveyed a strong social message, as she became active in the civil rights movement and grew closer to artists like Langston Hughes and James Baldwin. Among her most well-known songs is one she wrote after the Birmingham bombings in 1963, “Mississippi Goddam” (1964). The protest song, composed in under an hour, was selected in 2019 by the Library of Congress for preservation in the National Recording Registry for being “culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant.” Simone died at her home in France on April 21, 2003.

Other great artists: The most difficult part of this section is not having the space to include more people. Here are just a few influential African American artists with North Carolina ties.

▪ Jazz saxophone legend John Coltrane was born in Hamlet and grew up in High Point. Another jazz great, composer and pianist Thelonious Monk, was born in Rocky Mount, but left the South with his family when he was 5 years old.

▪ Durham native Betty Mabry Davis and Kannapolis native George Clinton are considered two of the most important funk musicians in American history.

▪ Five members of the James Brown Band — Maceo and Melvin Parker, Dick Knight, Nat Jones and Levi Raspberry — are from Kinston, which is sometimes referred to as “the birthplace of funk.”

▪ Blues guitarist Elizabeth “Libba” Cotten, born near Chapel Hill, was highly influential and known for her signature playing style, which came to be called “Cotten picking.” Her songs, such as “Freight Train,” have been covered by folk musicians Bob Dylan, Joan Baez, Jerry Garcia, Doc Watson and Peter, Paul and Mary.

▪ Durham native Shirley Caesar, an 11-time Grammy winner, is considered the “First Lady of Gospel Music.”

▪ Fayetteville’s J. Cole was the first hip-hop artist in 25 years to go double platinum without any guest features with his Grammy-nominated album “2014 Forest Hills Drive.”

▪ Winston-Salem’s 9th Wonder, born Patrick Denard Douthit, is one of the most influential hip-hop producers in the world. In 2007, he was named Artist-in-Residence at NC Central University in Durham.

▪ Thomas Day, a Virginia native who came to North Carolina as a teenager in 1817, was a free Black furniture craftsman whose work was not only highly sought after during his time, but is studied and displayed in museums today.

▪ Willie Otey Kay, a Raleigh native and Shaw University graduate, was a renowned dressmaker and entrepreneur whose work — which spanned more than six decades — has been displayed in museums. One of her gowns was featured on the cover of Life magazine in 1951.

▪ Poet and writer Maya Angelou was born in St. Louis but made her home in North Carolina for more than 30 years, starting with a professorship at Wake Forest University in 1982. She lived in Winston-Salem until her death in 2014. Angelou is best known for her memoir “I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings” and for her poem “On the Pulse of Morning,” which she read at the first presidential inauguration of Bill Clinton in 1993.

▪ Debra Austin, the first African American female principal dancer of a major American ballet company, was not born or raised in North Carolina, but she currently serves as the ballet master for the Carolina Ballet in Raleigh.

To learn more

Read: The NC Arts Council website’s African American Music Trails of North Carolina (www.ncarts.org/aamt/african-american-music-trail) has information about North Carolina’s Black musicians.

Watch: The 2015 documentary “What Happened, Miss Simone?” by Liz Garbus.

Read: A timeline of Nina Simone’s work and press coverage at NinaSimone.com.

Read: “Step It Up & Go: The Story of North Carolina Popular Music” by David Menconi.

Historically Black Colleges and Universities in NC

Dates: 1865 to present.

Synopsis: Education opportunities were rare for African Americans across much of the South prior to the end of the Civil War — when it was against the law to teach an enslaved person to read or write. Schools for higher learning were non-existent. The first college for Black people to open in the South was Shaw University in Raleigh, on Dec. 1, 1865, just eight months after the Confederate surrender at Appomattox. Shaw, initially called Raleigh Institute, was founded by Dr. Henry Martin Tupper, a Massachusetts native and soldier in the Union Army during the war. The school moved to its current site in downtown Raleigh in 1870 and was later renamed for donor Elijah Shaw. Shaw was the first college in the nation to offer a four-year medical program (1882-1918) and the first HBCU in the nation to admit women.

Other HBCUs in NC: Many other colleges, known as Historically Black Colleges and Universities, followed Shaw, with 12 total in the state: Shaw and St. Augustine’s in Raleigh; Fayetteville State in Fayetteville; Elizabeth City State in Elizabeth City; N.C. A&T and Bennett College in Greensboro; Winston-Salem State in Winston-Salem; Johnson C. Smith College in Charlotte; Livingstone College in Salisbury; North Carolina Central University in Durham; Barber-Scotia College in Concord ; and Kittrell College in Kittrell (now closed).

Impact: Though the National Center for Educational Statistics says enrollment at HBCUs has been on the decline in recent years, the schools — which admit students of any race — are still vitally important. HBCUs serve a larger percentage of first-generation college students and historically boast a higher retention rate for minority students. These schools also typically offer lower tuition and a supportive learning environment, and graduate a high number of STEM majors (science, technology, engineering and math).

Other key people and things: At the end of the Civil War, there was a big movement, fueled by Northern churches and aid societies, to educate freed slaves of all ages. Rosenwald Fund schools were one product of that movement. The schools were conceived in the 1910s by Booker T. Washington and the Tuskegee Institute staff, and funded by one of America’s leading philanthropists, Julius Rosenwald, president of Sears, Roebuck and Company. Rosenwald offered matching grants to build schools for African Americans in rural areas across the South. There were 813 of these Rosenwald schools in North Carolina, more than any other state in the country. Few of the buildings remain today. Also important in North Carolina was the Palmer Memorial Institute near Greensboro, founded in 1902 by Charlotte Hawkins Brown, the granddaughter of former slaves, as a high school providing academic and industrial education for African American youth. For decades, 90% of Palmer students attended college. The school began to decline after integration, and closed in 1971 after a fire destroyed its buildings.

Interesting facts: North Carolina Central University, whose founder James E. Shepard was a graduate of Shaw (and a founder of Mechanics & Farmers Bank in Durham), is the nation’s first state-supported liberal arts school for African Americans. Renowned historian Dr. John Hope Franklin wrote his seminal work, “From Slavery to Freedom: A History of Negro Americans,” while teaching history at N.C. Central (1943-47).

To learn more

Read: “The Education of Black People: Ten Critiques, 1906-1960” by W.E.B. DuBois.

Read: “Self-Taught: African American Education in Slavery and Freedom” by Heather Andrea Williams.

Read: “America’s Historically Black Colleges and Universities: A Narrative History, 1837-2009” by Bobby L. Lovett.

The Underground Railroad through North Carolina

Date: Early 19th century until the Civil War.

Synopsis: Years before Harriet Tubman famously escaped from bondage in Maryland and became a leader in the effort to help others do the same, enslaved people were traversing the hills, swales and swamps of North Carolina on their way to freedom. Sometimes they had help. The National Park Service has identified 15 sites associated with the Underground Railroad, a secret system through which fugitive slaves could escape to states where they would be considered free. The Underground Railroad borrowed language from the real railroads that began to appear in the 1820s. Escapees who were “passengers” or “freight,” hiding at “stations” during the day and moving at night with the help of “conductors.”

Key people and places: Among the most noted conductors in North Carolina were cousins Levi and Vestal Coffin, Quakers who lived in the New Garden community in Guilford County and grew tired of waiting for a legal end to slavery. From 1819 until 1826, they helped an unknown number of slaves escape, many of them to Indiana, by hiding them in what became known as the New Garden Woods. Other stations in North Carolina included the Roanoke Island Freedom Colony, Orange Street Landing in Wilmington and the Great Dismal Swamp, where researchers believe hundreds to thousands of escaped slaves lived in “maroon colonies” beginning in the mid-1700s.

Impact: There is no way to know exactly how many people escaped slavery before emancipation in 1863 and the passage of the 13th Amendment in 1865, but estimates are as high as 100,000.

Related: Harriet Jacobs, born into slavery in Edenton in 1813, hid for seven years in an attic space above a storeroom at the home of her grandmother, a free Black woman, to avoid sexual assault from her master. In 1842 she escaped by boat to the North, eventually reuniting there with her children. Her book, “Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl,” was the first slave narrative by a woman and included descriptions of the sexual abuse she experienced.

Interesting fact: Slaves were sometimes spirited to freedom by hiding under false bottoms in loaded wagons. Such a wagon and other Underground Railroad artifacts are displayed at the Mendenhall Homeplace, a Quaker historic site in Jamestown.

Black military members in North Carolina

Date: Pre-Revolutionary War to the Present

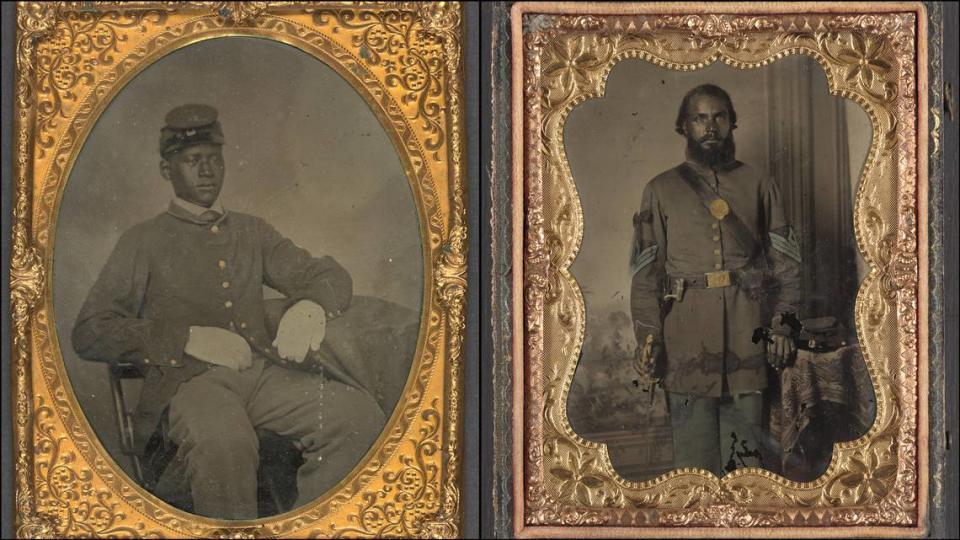

Synopsis: Black people have volunteered or been conscripted for service to America since colonial days, when free Black men joined their local militias. During the Revolutionary War, they initially were barred from serving as Patriots, in large part because slaveholding states feared arming enslaved men for battle would result in uprisings. But after the British governor of Virginia began promising freedom for slaves who volunteered as Loyalist soldiers, then-Gen. George Washington decided to ask for their help as well. Estimates are that 5,000 Black men fought for American Independence, sometimes integrated into existing regiments and sometimes mustered into ones of their own. Some enslaved men were sent into service in the place of their masters. One researcher has counted 468 Black men from North Carolina who served under the American flag during the conflict.

In the Civil War: At least 5,000 Black men enlisted with Union regiments in areas of Eastern North Carolina occupied by Union troops. The First North Carolina Regiment of Colored Volunteers was one of the first regiments made up mostly of former slaves. Other free Black people provided labor for the Union army, working as cooks, handling laundry or serving as personal aides to officers. Some freed Black men worked for wages for Confederate troops based in North Carolina, but none are known to have served in combat as Confederate soldiers.

In World Wars I and II: A fourth of the 86,000 troops from North Carolina who served in World War I were Black, and they often faced racial harassment and discrimination in pay and job assignments. When the war ended in 1918, African Americans who had fought on behalf of the U.S. found the nation still refused them social and economic equality. During World War II, President Franklin D. Roosevelt opened the military to the recruitment of Black men, and the next year pushed the Marine Corps to begin doing so. Still reluctant to integrate African Americans into the ranks, the Marines set up a separate boot camp called Montford Point next to Camp Lejeune, and trained more than 20,000 Marines there over the next seven years. About 2,000 Montford Point Marines took part in the seizure of Okinawa.

Impact: The U.S. military is a microcosm of society with the same prejudices that exist outside it, but its structure and discipline allow for the imposition of social change in ways that don’t happen in civilian life. So when the military changed policy to prohibit racial discrimination and harassment, violators could be punished. After World War I and again after World War II, African Americans leaving the military were re-energized in their fight for equal treatment in civilian society.

Interesting facts: In today’s all-volunteer U.S. military, Black people are overrepresented, making up 17.1% of all active duty service members and 16.8% of the total force, including reserve and guard troops. Black people make up 13.4% of the U.S. population. The first casualty of the Revolutionary War was a Black man named Crispus Attucks, who was shot by the British in the Boston Massacre.