Doctors Explain Why Autoimmune Diseases Have Baffling Symptoms and Triggers

If it seems like everyone knows someone who suffers from an autoimmune disease, that’s because the term is a giant bucket that holds a vast variety of conditions, some as well-known as multiple sclerosis or type 1 diabetes, and as rare as Asherton’s Syndrome, which causes blood clots in organ systems throughout the body.

Add them all up and some 23.5 million Americans are affected, according to government statistics, more commonly women than men. What’s more, autoimmune diseases are on the rise for reasons experts don’t yet fully understand—and they’re a leading cause of death and disability.

So, what should you know about these mysterious disorders? Ahead, important facts to key you in to what autoimmune diseases are, how they affect the body, and the symptoms they’re most often associated with.

1. The immune system is like an army.

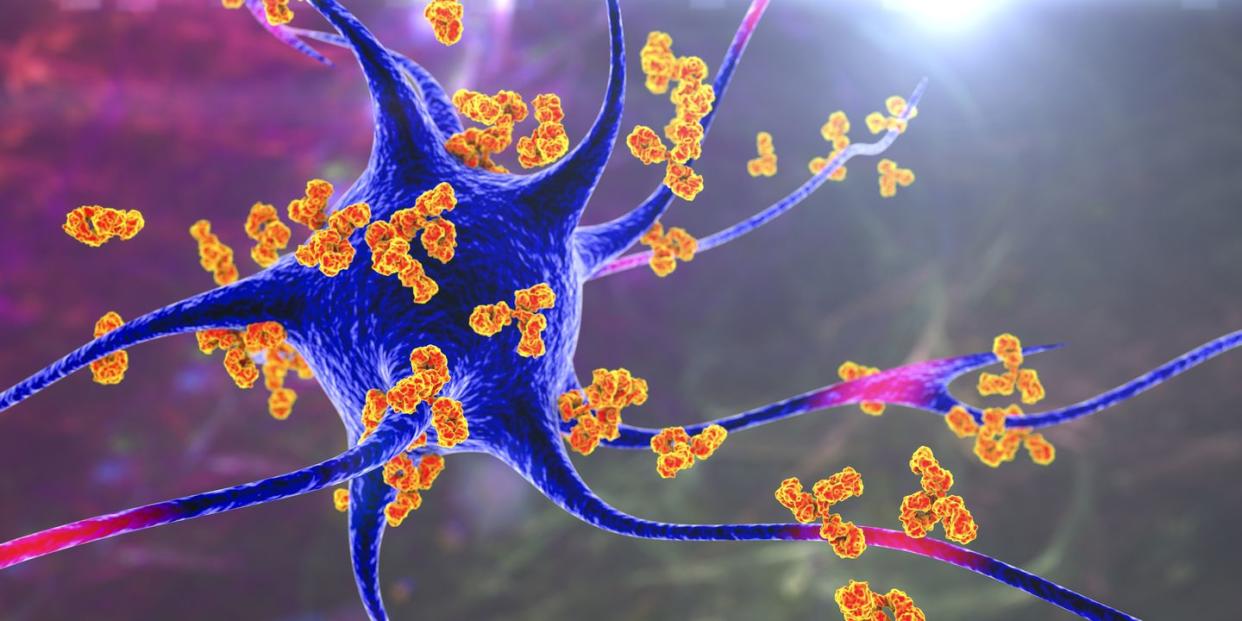

It guards against disease-causing organisms by releasing its soldiers (a.k.a. antibodies), proteins in the blood meant to neutralize a threat. This is the immune response. “It spends the earliest years of your life distinguishing friends from enemies so it can protect you from invaders,” explains Anca Askanase, M.D., director of the Columbia Lupus Center.

But sometimes the immune system mistakes healthy cells for an invader and sends antibodies to attack them, which is what happens when you have an autoimmune disease. This assault on healthy cells can happen anywhere in your body, from your skin (as in psoriasis) to your thyroid (as in Hashimoto’s disease).

2. Autoimmune diseases run in families.

Doctors know there is a genetic component to autoimmune diseases and that certain ones are more common in specific ethnic groups. For instance, lupus (painful and damaging body-wide inflammation) is more likely to affect African-American, Hispanic, Asian, and Native American women, while Caucasians are more likely to develop type 1 diabetes (in which the pancreas produces little or no insulin).

Recently, doctors have learned that a single gene may cause different diseases in different people—you might have Crohn’s disease (which affects the digestive system), while the same gene gives your mother alopecia (in which the immune system targets hair follicles).

“Some genes carry risk for multiple diseases, and some increase risk for just one,” says Timothy B. Niewold, M.D., director of the Judith and Stewart Colton Center for Autoimmunity at NYU Langone.

Environment also plays a role, via exposure to chemicals and pollutants in the things we eat and use. “For instance, we know smoking increases the chances of developing rheumatoid arthritis twofold,” says Dr. Niewold, “and people may have different levels of susceptibility.”

3. Symptoms can appear suddenly.

An autoimmune disease may seem to come out of nowhere or arise after an unrelated illness—even a common one like the flu—so scientists are looking into whether viruses or infections could be triggers.

One virus being studied for a possible connection to lupus and multiple sclerosis (MS) along with other autoimmune diseases is the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV). Most people encounter EBV at some point in their lives, and usually it stays dormant in the body. But researchers have found early evidence that for some people EBV “turns on” the gene associated with these autoimmune diseases, increasing the chances of developing one of them.

4. More women get autoimmune diseases.

A full 75% of the 23 million sufferers in the U.S. are women, but it’s unclear why. “We can tell that women have a stronger immune response in general, because men are about two times as likely to get cancer and infections,” says Johann Gudjonsson, M.D., Ph.D., the Arthur C. Curtis Professor of Skin Molecular Immunology at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. “That stronger response is a double-edged sword: It’s good for protection, but it predisposes women to an out-of-control immune system.”

5. Some autoimmune disorders have the same symptoms.

“Many autoimmune diseases have symptoms in common,” says Dr. Askanase, and many of these can be signs of something else entirely. “Often one of the first clues is extreme fatigue, which might be dismissed by doctors as simply a consequence of being overworked,” she says.

There are approximately 100 known autoimmune diseases, and most have overlapping symptoms: diarrhea (celiac disease, Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis), fatigue (celiac disease, fibromyalgia, Guillain-Barré syndrome, lupus, MS), hair loss (alopecia, Hashimoto’s disease, scleroderma), joint pain (rheumatoid arthritis, MS), and rash (dermatitis, lupus, psoriasis).

6. A sensitive stomach may be a sign of an autoimmune condition.

Tummy troubles are ubiquitous and are often due to a virus or something you’ve eaten. But if they are persistent or flare up periodically along with more extreme symptoms like bloody stools, pain, night sweats, and fever, it could be irritable bowel syndrome, a group of autoimmune disorders that cause chronic inflammation of the digestive tract.

It makes sense that other autoimmune diseases involve gastric issues too: Seventy percent of the cells that control immunity reside in our guts—command central for the immune system. Scientists at Yale University are looking into a connection between lupus-like autoimmune diseases and a faulty gut barrier that allows gut bacteria to travel into organs.

7. Yes, you can be too clean.

Our increased reliance on antibacterials for cleaning our homes and hands may be partly responsible for our out-of-whack immune systems. The oft-debated hygiene hypothesis is based on the idea that the immune system develops in response to encountering bacteria, viruses, and other germy conditions.

It claims children are being raised in “too clean” environments with overexposure to antibiotics and other environmental chemicals and underexposure to dirt and microbes. Then when the immune system is called on to act against a bodily invader, it doesn’t know how to react and may go into overdrive.

8. Diagnosis of autoimmune disorders is not an exact science.

It’s hard to develop a test for a disease when you don’t know what is causing it. “There are no perfect tests yet,” says Dr. Niewold. One looks for antinuclear antibodies (ANA): “If you have lupus, you’ll test positive for ANA,” he explains. “But patients with many other conditions would have a positive response, as would some healthy people.”

Doctors need to watch for a constellation of factors, Dr. Niewold says. They should take into account physical symptoms—including their severity—along with family history and the ANA blood test.

9. You might need to be persistent.

One of the first clues that you have an autoimmune condition may be a vague sense of not feeling well. Many doctors, when they hear something so unspecific—especially when it involves tiredness or even brain fog and hormonal swings—are likely to dismiss concerns, misdiagnose the problem, or refer the patient to a psychologist.

For example, “Hashimoto’s thyroiditis symptoms might be mistakenly brushed off as perimenopause or depression,” says Mary Vouyiouklis Kellis, M.D., an endocrinologist at Cleveland Clinic. Plus, many autoimmune symptoms can come and go.

So if your instinct is that something is not right, be your own advocate: The average patient will see four doctors over four years before receiving a correct diagnosis. If you suspect that you have an autoimmune disease, keep a list of unusual symptoms, no matter how mild, infrequent, or long ago.

10. We’re learning more about autoimmune diseases every day.

Despite all that is unknown about autoimmune diseases, researchers are hopeful. Dr. Niewold believes autoimmune diseases are an outgrowth of our bodies’ effectiveness at

fighting infections, so scientists are looking for ways to “reeducate” the immune system.

“The immune system is really good at remembering the cells it needs to attack; we now have to learn how to redirect the immune response when it targets normal organs and tissues,” he says. “We have been making so much progress.” There is much more on the horizon, he adds, including gene therapy and possible vaccination.

You Might Also Like