How the $100 million proposed reopening of a former gold mine has angered Grass Valley

Ben Mossman believes one of the largest amounts of unmined gold in the world lies deep under the ground in Grass Valley and wants to extract it. And that has made him, and his Rise Gold Corp., public enemy No. 1 in this town.

Sixty-eight years have passed since the Idaho-Maryland Mine operated in this small city in the Sierra Nevada foothills, about 50 miles east of Sacramento. Grass Valley residents want to keep it idle, a relic of the past.

Residents cite concerns that the 2,585-acre mine site would create failed wells, groundwater contamination, noise pollution and air pollution and increased truck traffic. Mossman said he and environmental studies have rebutted all those fears. He promises a mine that won’t damage the environment and will create an economic boom.

“There are some people who are just trying to stir up fear intentionally,” said Mossman.

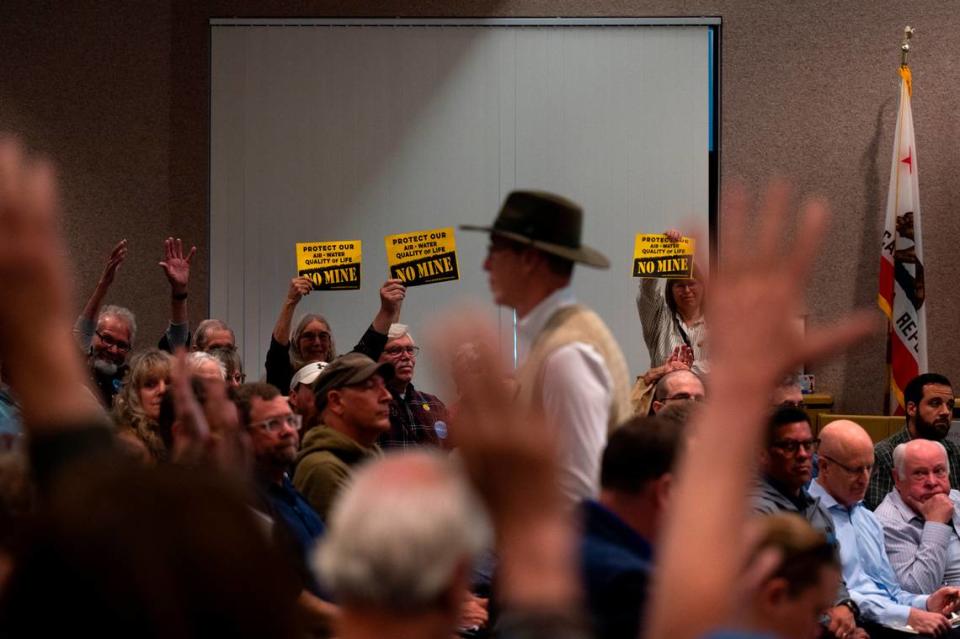

Not so, residents counter. Opponents crowded two days of hearings with the Nevada County Planning Commission last month, overflowing outside listening to testimony near a tent, with a “no mine” banner, that had audio piped in.

Penny Collins was one of nearly 400 residents who attended the hearings. She said Grass Valley has already seen three wildfires and several power outages in the last few years.

“I just can’t understand, given the other environmentally related and weather related things that we have going on here, how my kids are going to be safe,” she said. “I have a 19-year-old and a 16-year-old and I just feel kind of overwhelmed by what their future would look like.”

The planning commission agreed with the opponents. It rejected the plan to reopen the mine.

But the final decision will be up to the Nevada County Board of Supervisors, which could take up the matter in August.

County Planning Board Chairman William Greeno said the mine in itself isn’t a bad idea.

“I think this could be an amazing mine project somewhere,” he said. “The problem is it doesn’t belong on the project site.”

In a June letter 5 letter to the Board of Supervisors, Mossman accused the planning board and planning staff of being “biased” since he presented his plan to reopen the mine in late 2019.

He said the planning board in May ignored expert testimony that the project would have no significant environmental impact and excluded proponents of the project from speaking at the hearings by giving opponents tickets at 7 a.m., leaving project proponents shut out when they arrived at the stated 8:30 arrival time.

“While we recognize that the biased actions of the Planning Commission and other County representatives throughout the Project entitlement process do not necessarily reflect the manner in which the Board will consider the Project, we are concerned that the demonstrably biased disposition may influence the Board’s decision,” Mossman wrote.

A spokesperson for Nevada County did not respond to a request for comment on Mossman’s letter.

Grass Valley has changed

Grass Valley is obviously not the same town since the closing of the mine. It has gone upscale. The mine is seen by some as an artifact from another era, when long, risky labor was the only means of survival in this once-frontier town.

Some descendants remain of the Cornish miners who came from England to dig up gold in more than 500 miles of tunnels in Grass Valley and nearby Nevada City. But, today, the gold connection is strictly for tourists.

State parks on the site of old mines in Grass Valley and surrounding communities offer a glimpse of the gold rush in the 1860s that brought tens of thousands to this area looking to strike it rich or just to have steady work.

Today, the small downtown of Grass Valley is full of gold-rush era buildings occupied by wine tasting rooms, fancy restaurants and art galleries, far removed from actual gold mining.

Adding to the Western chic atmosphere are a downtown performing arts center with several stages and a new director from New York City and a kombucha brewery with a stage featuring musical groups and aerial acts.

What the plans are

Gold history is one thing, but a working mine, despite the promise that it won’t hurt the environment, is the last thing anyone seems to want.

The county planning staff in its recommendation to the planning board didn’t disagree with Mossman that mining activities could be conducted in an environmentally safe way.

The planning staff had reviewed a more than 800-page environmental impact report paid for by Rise Gold but done by an independent consultant.

But planning staff found that reopening the gold mine was not consistent with the county’s overall general plan to maintain the rural characteristics of Nevada County.

Mossman, who moved from Vancouver, Canada, to Grass Valley after Rise Gold purchased the mine, has promised 300 high-paying jobs that pay $145,000 annually on average from mine operations. He said it would generate $6 million in local taxes each year, 10 times larger than any one taxpayer now.

“It would be an economic boom to Grass Valley,” he said.

But Grass Valley isn’t desperate for jobs. Nearly 25% of city residents are elderly, almost twice the rate of California overall. Recent arrivals include second-home buyers looking for a rural escape in an artsy town and remote workers who don’t have to live in a major city.

Publicly traded Rise Gold, has already invested $25 million in its plan to revise the mine, including $2 million to buy the abandoned mine.

Mossman has anticipated spending $100 million to reopen the mine but sees a big payout for Rise Gold based on previous gold production at the mine.

Mossman’s background

Mossman, 45, is an engineer and grew up in Vancouver Canada. He has worked in mines in both Canada and South Africa.

Mossman was involved in controversy before the Grass Valley mine project.

Banks Island Gold, a Mossman company, ran a gold mine on the remote Banks Island off the coast of British Columbia. The mine was on the land of the indigenous Gitxaala Nation, which opposed the mine, citing environmental concerns.

Mossman began mining operations in 2014 but the next year mine inspectors cited his company, saying mine waste and contaminated water were leaking into creeks, ponds and wetlands.

Bank Island Gold declared bankruptcy in 2015 several months after the British Columbia government shut down the mine.

The government confiscated the company’s $420,000 reclamation security deposit and has removed explosives and hazardous materials from the land as well as monitoring water quality.

Mossman and his chief geologist went on trial last year on 16 offenses related to the mine spills. A previous trial resulted in acquittals on all but two of the charges, but a new trial was ordered by an appeals court.

A judge was expected to announce on June 19, a date for a verdict in the civil case, said Dan McLaughlin, a spokesman for the British Columbia Prosecution Services in an email.

Mossman won’t discuss the case.

Large amounts of gold

What he will discuss is the potential in Grass Valley.

In its nine decades of operation, the mine produced 2.4 million ounces of gold. At today prices of around $2,000 a ounce, that’s almost $5 billion dollars.

Exactly how much gold is left is unclear, but Mossman believes it’s a lot.

He said what got him excited about owning the mine was after he came across the government summary of mining that was going on in the early 1940s.

“They talked about how the mine had just completed an expansion in 1942 to double the production,” Mossman said. “So to go from 1,000 tons to to 2,000 tons per day. It was already the second largest gold mine in the entire U.S.”

But the increased production never occurred because all U.S. mines were shut in 1942 as part of the federal government’s World War II effort. The government’s focus shifted from gold because it did not produce minerals that could be used to aid the war effort.

The government put the spotlight on producing other metals such as copper and iron to boost the production of equipment, ships, tanks, airplanes and bullets.

The mine reopened after the war but the price of gold was fixed at $35 an ounce thanks to the 1944 international Bretton Woods agreement.

“Mining gold wasn’t profitable any more,” said Mossman

The agreement was scrapped in 1971 and the value of gold recently has stayed high for investors who view it as a hedge against inflation and the value of the dollar.

Mossman said he is pretty sure a large amount of gold is in the ground to justify the $25 million Rise Gold has spent. Rise Gold had conducted exploratory drilling, which found gold, but he conceded the exact amount is impossible to determine.

“If you could bring back production and achieve the success of the past, it would be among the highest grade major gold mines in the world,” he said.

Mossman said in the past gold was extracted to 1,600 feet below the surface. “And you can mine to a depth of 10,000 feet before it gets too difficult,” he said. “So, there is a lot of room left for mining.“

Mossman feels residents are misinformed about what they think is the mine’ s detrimental consequences.

“We’ve gone through a lot of work to design the project to the high standards in Nevada County and what we think is going to be the most environmentally friendly gold mine in the world,” he said.

Mossman said the mine will be creating gold concentrate, not the finished product of gold bullion, meaning it won’t have to use environmentally dangerous chemicals such as mercury and cyanide.

“So we don’t use any harmful reagents,” he said.

Residents worried

Most residents have not been reassured, especially those close to the mine.

A big concern to residents is the dewatering of the mine, which became flooded with rainwater after it closed in 1956. An estimated 815 million gallons of water would have to be pumped out, 3.6 million gallons of day, which would take six months, the first part of a three-year plan to reopen the mine.

Once the mine is dewatered, another 1.2 to 3.6 million gallons per day would continue to be pumped from the underground workings to maintain the dewatered state.

Many homeowners here are dependent on well water. Homeowners worry that the dewatering could affect the network of fractures and faults in the rock that fill with water and provide the water supply to wells.

The environmental review found that the wells of eight homes could see a decline in their water levels, though the study said none would go dry.

Mossman has agreed to hook up those homes and another 22 closest to the mine to the treated water supply managed by the Nevada Irrigation District.

But 527 homes with wells lie above site where gold would potentially be mined. Many residents worry regardless of the environmental study finding that only a few homes would potentially be affected.

Ricki Heck’s home is a mile away from the mine but is not one of the homes in the remedial plan scheduled to get water from the Nevada Irrigation District if things go wrong from the mine.

Heck, a real estate broker approaching 70, said she and her 72-year-old husband want to downsize from their 4,000-square-foot-plus house, to move to a smaller residence. But she said that just the potential fear of wells being contaminated from the mine are keeping people from buying their residence.

“We have to sell that house,” she said. “We cannot live there and take care of it at our age anymore. I tried to sell it two years ago, and the cloud of this has made it unsellable.“

The Nevada Irrigation District is concerned that more wells than expected could be affected by reopening the mine and asked the planning board at the May 9 hearing to require Rise Gold to put up a $14 million bond to cover the cost of 527 additional hookups to its treated water system.

District General Manager Jennifer Hanson said in the letter that “a high level of uncertainty” surrounds the accuracy of predicting how many homeowners wells could be affected given climate change and the difficulty of accurate modeling well failures.

Hanson warned that the irrigation district would not be responsible for supplying water to connect homes if wells failed. She said even if the county or Rise Gold had the resources to pay, “connections could be delayed, or worse not happen.”

Rising tension

For some, talk of the mine has become personal, particularly when Mossman’s name comes up.

Rick McNulty, an engineer, remembers his initial dealings with Mossman after he purchased the mine and began exploratory drilling in 2019.

McNulty’s house is several blocks from the mine site. He said noise from a generator powering the exploratory drilling was so annoying that he talked to Mossman, who told him not to worry.

“He seemed nice and honest,” McNulty said. “He promised the noise wouldn’t get any worse, and that it would eventually stop.”

But McNulty said just a week or two later Mossman installed a “diamond drill.”

“It created a loud, high-pitched howl that echoed through my neighborhood for up to 18 hours a day,” McNulty said. “There were days I thought my ears would bleed.“

McNulty said the noise only ceased after he gathered a petition of neighbors and complained to the county, which forced Mossman to install a $10,000 soundproofing enclosure.

“Beware of Ben Mossman,” he told the planning board.

Mossman said in an interview that the noise was within limits.

Nevada County spokeswoman Taylor Wolfe said county inspectors responded to McNulty’s complaint. She said the noise was found to be within acceptable limits. Wolfe said the county closed the complaint after Mossman agreed to install walls around the drilling apparatus “to further buffer any noise.”

Worries about a history of pollution

Residents are also concerned because a secondary Idaho-Maryland Mine site in 2020 was found to have high concentrations of lead, mercury and arsenic.

A Rise Gold subsidiary owns the 56-acre mine waste disposal area that was used for dumping mine waste until the Idaho-Maryland Mine closed.

The site was listed as a potential federal Superfund site site until Rise Gold agreed to conduct a cleanup as part of the agreement with the California Department of Toxic Substances Control.

Rise Gold’s permit application to reopen the mine calls for the removal of 1,500 tons of rock per day, 24-hours a day. During the 80-year project timeline, 2.4 million cubic yards of mining tailings and rock waste would be deposited at the main mine site and the secondary site once the environmental cleanup is finished.

A Rise Gold spokesman said the mine tailings and rock waste would be in handled in an environmentally safe way that would not use mercury or cyanide.

Lawrence Lepard, Rise Gold’s largest shareholder thinks environmentalist are drowning out others.

“I think what’s happened here is a small group of very loud environmentalists, who haven’t even, in my opinion, taken the time to think through the environmental report, have come to the conclusion the report’s not true.”

Lepard, who owns 11% of Rise Gold, said the company is still intent on working with opponents and addressing their concerns.

He said the mine will be a “win-win” for everyone in Grass Valley.

“What I think very few people realize this is one of the best gold deposits in the entire world. I mean, the entire world, all deposits that have ever been mined,” he said. “This is going to be like in the top 2%. And that’s why guys like me, we want to see it brought back because we know that it will produce and produce gold for 20, 30, 40 years.”