100-year-old fought in WWII then fought for civil rights in Montgomery

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Montgomery resident W.J. Williams was 31 when Rosa Parks was arrested and local pastor Martin Luther King Jr. called for a bus boycott. Williams, a World War II veteran, was moved to help. And he had a car.

A friend had stopped by his house to share the news of Parks' arrest and invite him to the first of many civil rights meetings. There, at Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, Williams listened as King presided over the gathering where a group of Montgomerians decided to boycott city buses.

The boycott would last for 13 months and bring the city to its knees. Williams was one of more than 200 people who dedicated himself to helping neighbors get where they needed to go during the protest.

“We had been mistreated so many times on that bus," Williams said on Jan. 19, 2024, the day after his 100th birthday.

So, when Williams saw Black people on foot, he would stop and drive them as far as he was going, and after Williams finished his route delivering mail for the post office, he would drive down Narrow Lane Road and give a ride to whoever needed it.

“You didn’t charge anybody anything. You were glad to do it," Williams said.

Pretty soon, Williams said, “those buses was running empty."

More: The Bus Boycott in Images A look back at the Montgomery Bus Boycott

More: Memories of the Bus Boycott 'None of us knew where it was going to lead': Reporter recalls early days of bus boycott

A family affair

For the Williams family, doing their part for civil rights was a family affair. His mother, Lilly Jane Thomas Williams, attended every bus boycott meeting alongside her son, the youngest of her five children. She brought peppermint candy to share with her friends.

“She was always kind of fiery anyway, and she didn’t like what was going on," W.J. Williams said.

Williams helped a cousin, David W. Williams, run one of the first Black-owned and operated service stations in Montgomery. David gave gas to the people who were driving the boycotters, said his son, Norbert.

Williams' nephew, the Rev. Frederick D. Reese, helped organize the Selma-to-Montgomery March about 10 years later.

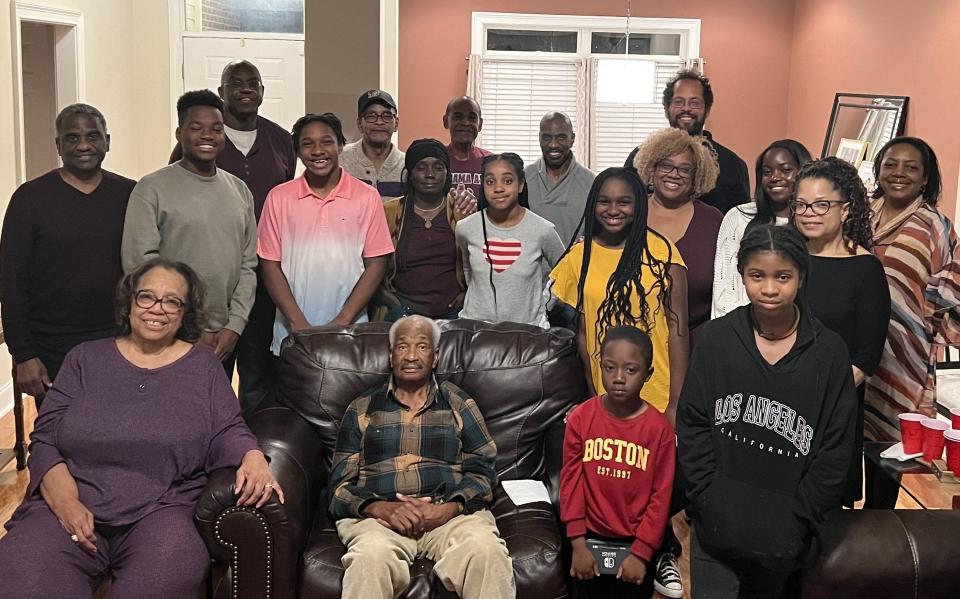

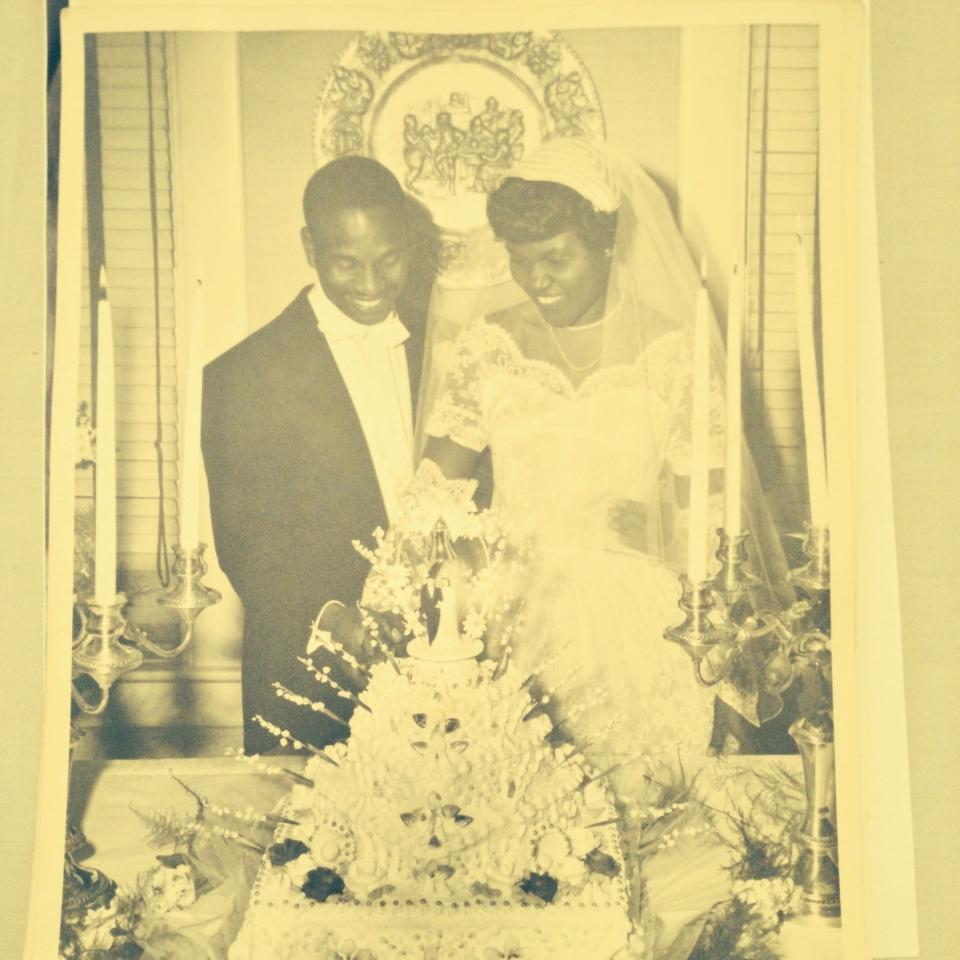

Williams and his wife, Mildred, passed on their values to their four sons, seven grandkids and four great-grandchildren. Mildred died in 1982. Williams later married Mattie Walthall, who died in 2019.

“I don’t know of anybody that was along with me, that grew up along with me, that are still here," Williams said.

The day after his 100th birthday, Williams said that he didn't expect to live a century, especially growing up at a time when he remembered people dying at 50.

“I enjoyed everything and so forth. I’m just thankful. I never thought I would see 100 years, but the Lord has blessed me."

Surviving the siege

When the Freedom Riders arrived in Montgomery in 1961, they were greeted with violence at the bus station. The Ku Klux Klan then bombed four churches in the early morning hours. That evening, Williams was sitting in First Baptist Church, where King was holding a meeting. The congregants heard an explosion outside. The attack became known as "the siege of First Baptist," where the Freedom Riders sought shelter.

More: First Baptist 150 years: The legacy of First Baptist Church

King reassured the congregation, and the people there stayed for most of the night. The FBI eventually surrounded the church, allowing the attendees to walk home in groups.

Williams recalled worrying about getting back to his oldest son, who was just a baby at the time, and his pregnant wife. He was nervous he would not get to work on time. But for the most part, he said he was not scared. Part of that was because of King.

“Shoot, I’m telling you, you would walk a mile just to listen to him," Williams said about King. "He had a booming, eloquent voice. When he spoke, you were just sitting there with your mouth open. I never heard a man who could speak like that."

Williams said he went to go hear King speak as often as he could.

Serving in WWII

Prior to fighting for equality in the United States, Williams served in the Navy, which remained segregated throughout his assignment in World War II. He shipped off to the South Pacific in 1944 and remained there until the end of the war.

His youngest son Damund said that buddies in the Navy reported back that he did not curse, gamble or drink. Throughout his time in service, he also continually sent money home to his family.

Williams said his biggest fear was being buried at sea.

“I always wanted to get back home to see my family," Williams said.

More: She was 13 when a beaten John Lewis arrived at her Montgomery family's home, seeking refuge

When he returned from overseas, he resumed his studies at Tennessee State University, where he graduated in 1947 and then returned to Montgomery, his home and birthplace.

In Montgomery, Williams led by example. In 1956, he became a deacon at Hutchinson Missionary Baptist Church. He also served as the secretary for the Board of Deacons for a span of 35 years.

“All of my life I’ve been active in church services," said Williams, who remains a deacon at the church in 2024.

In 1950, the church named him chairman of the trustee board. He helped with the construction of two buildings for Hutchinson. The creation of the highway destroyed the first church.

For the last century, the world was not always kind to Williams. The KKK chased him. The Postal Service assigned him the tough routes — the ones with dogs and difficult customers. He lived his first 40 years in segregated Alabama. Despite that, those who know him said he's always been quick to offer a smile and a kind word.

“I’m just grateful," Williams said. "I’m just so blessed."

Alex Gladden is the Montgomery Advertiser's public safety reporter. She can be reached at agladden@gannett.com or on Twitter @gladlyalex.

This article originally appeared on Montgomery Advertiser: Centenarian recalls bus boycott, siege of First Baptist, WWII