America responded to Pearl Harbor by sending some Japanese Americans to internment camps

The last of a generation of Americans of Japanese ancestry to be forced into northeastern California's Tule Lake prison camp during World War II wants everyone to remember how quickly people can lose their precious civil rights.

Those still speaking out include Jim Tanimoto, who lives in Gridley. He said he doesn’t want what happened to him and his family during the war to ever happen again.

“There’s not many of us left now. This happened 81 years ago,” said Tanimoto, who celebrated his 100th birthday on June 3, shortly before speaking about his family's ordeal with the Record Searchlight.

What happened at Tule Lake?

Located in Modoc County near the Oregon border, an 84-mile drive through wilderness northeast of Weed, Tule Lake National Monument bears little of the splashy signage that tourists find at other national parks.

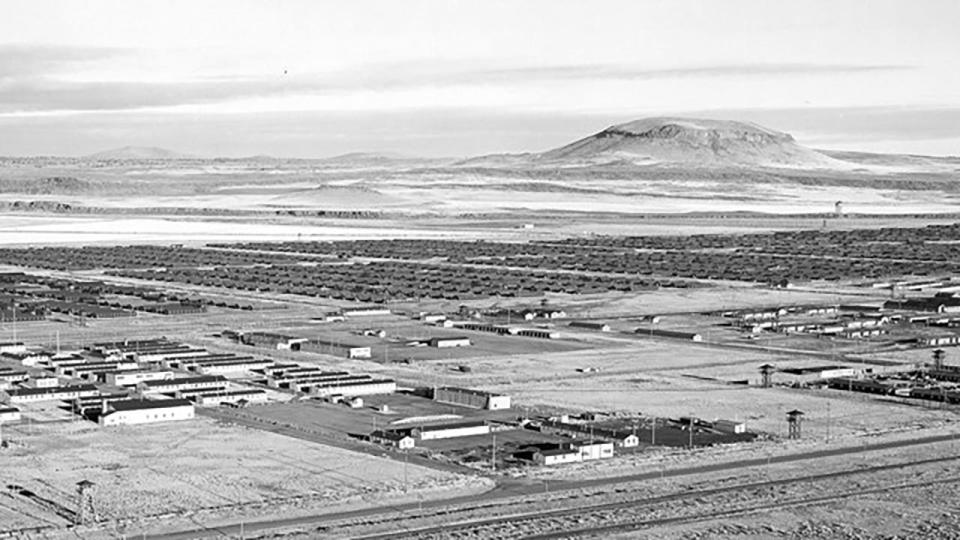

The Tule Lake Segregation Center was the largest of the nation’s 10 prison camps — formerly called internment centers.

From 1942 to 1946, Tule Lake housed 27,000 Japanese Americans, according to the National Parks Service. Two thirds of those held at at the North State detention center were American citizens.

The rest "were first-generation immigrants who, due to discriminatory immigration laws, were denied the right to become U.S. citizens” until 1952, according to Barbara Takei, a member of the Tule Lake Committee, a group working to collect and save survivors' stories that lobbies to preserve the camp’s site because of its historical significance.

Incarceration of Japanese Americans in detention camps was deemed necessary “to protect the country from potential acts of espionage or sabotage that might be committed by someone of Japanese ancestry," according to a study published by the American Psychological Association in 2019. However, a government investigation in 1980 found no evidence to support that fear, calling the mass incarceration "a grave injustice fueled by racism and war hysteria," the association's study said.

Over the four years the detention camp operated, 331 adults and children being held at Tule Lake died there, said Takei.

People who protested or were accused of protesting at any of the camps ended up at the Tule Lake Segregation Center's maximum-security facility for dissidents, which was equipped with a stockade and jail on the grounds, according to the National Parks Service.

After being released at the war's end, some prisoners spoke out about having been held against their will. But most were so traumatized by their experience in the camps that they kept their stories to themselves. Some even blamed themselves for not being “more American" and felt humiliation and shame, the American Psychological Association study said.

Takei called their race-based detention “a hateful response to fear and anxiety that was also used by political leaders during World War II, a rationale to strip the entire Japanese American population on the West Coast of rights, property and freedom and to forcibly remove them to concentration camps.”

While incarcerated, many Tule Lake survivors lost their homes and properties. After the camps were disbanded, those survivors would meet periodically with other prison camp survivors over the years for social support, first in San Francisco and Sacramento — and then at Tule Lake.

The Tule Lake Committee still hosts gatherings every two years at the camp for survivors and their families.

How Pearl Harbor led to the imprisoning of 27,000 Japanese Americans in far Northern California

With Congress’ passage of the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, survivors said many of those who had been detained felt compelled to finally share their stories in schools, books and news outlets. The 1988 law acknowledged the injustice of internment, apologized for it and provided a $20,000 cash payment — equivalent to just over $51,000 today — to each person who was incarcerated, according to the National Archives.

Now, decades after the internment camps closed, just a few detainees are left to educate people who are unaware of what happened there, Takei said.

With the FBI reporting that race-based attacks against people of Asian heritage are on the rise in the U.S., some Tule Lake survivors and their families worry that history could repeat itself.

Note to readers: If you appreciate the community journalism we do here at the Redding Record Searchlight, please consider subscribing yourself for giving the gift of a subscription to someone you know.

To those who doubt Americans could again be denied freedoms due to their race, Tanimoto said: “I say look at the Black people. Look at the (Native Americans). All were denied due process of the law.”

Imprisoned at Tule Lake: Under armed guard, with 'a view of Mt. Shasta'

Tanimoto was born in 1923 in Marysville, the son of Japanese parents who migrated from Hiroshima in the early 1900s.

Like most Japanese immigrants, his family farmed, said Tanimoto, who grew up with four brothers and two sisters in the family's home in Gridley in Butte County. They grew peaches for a local cannery, he said.

The 1913 Alien Land Law prohibited Asian immigrants from owning land. They were forbidden citizenship, based on their race.

In the 1920s, California law also barred American-born children of Asian immigrants from leasing or buying land. So the family bought their farm in the name of a trusted friend who was an American citizen, Tanimoto said.

On Dec. 7, 1941, the day after the Japanese military attacked Pearl Harbor in Hawaii, Congress declared war, entering World War II.

Tanimoto and his family were automatically declared enemies of the United States. American troops came for them in July, 1942, including his older sister’s four young children, Tanimoto said.

“When we left, it was a few days before” 1,000 tons of peaches “were ready for harvest,” he said. With the family gone, the fruit fell to the ground and rotted, he said.

Guards bussed the family to Tule Lake, said Tanimoto. Block 42 became his home. He and his four brothers lived in a 16-foot by 20-foot room in military barracks covered with tar paper.

“We were behind a barbed wire fence and guard towers. There were American soldiers with rifles and machine guns" patrolling the camp, Tanimoto said.

Searchlights "shined on us every night," he said.

Temperatures soared over 100 degrees in summer, then dropped below zero in winter.

“Dry weather would form cracks in the floorboards” and wind blew dust and dirt under the walls, coating the few personal items the family was allowed to bring with them to the camp, Tanimoto said. He and his family battled dust devils, whirlwinds, scorpions, mosquitoes and rattlesnakes.

The camp was exposed to the sun in an area so barren, Tanimoto said he had "a view of Mt. Shasta," more than 70 miles to the southwest.

People held at the camp did what they could to keep their children educated and their families fed. They grew their vegetables over acres of drained lake bottom, eating what they farmed, according to Tanimoto.

“The camp was like a city," he said. "We had post offices, we had banks, we had schools. Each morning, the school children would recite the Pledge of Allegiance while circling the American flag."

He and some other prisoners earned permits allowing them to leave the Tule Lake camp for short periods. Tanimoto said he would walk a mile to Castle Rock, an 800-foot bluff that was once an island in the drained lake.

“When you’re up on top, you can see the geese flying under you," Tanimoto said.

A replica of a cross placed there by those incarcerated at Tule Lake stands on Castle Rock in the Tule Lake National Wildlife Refuge.

How Pearl Harbor led to the internment of 27,000 Japanese Americans in the North State

Tanimoto returns home

After the U.S. government released Tanimoto and most of his family from the camp on Feb. 26, 1944, the vice principal of Tule Lake High School drove them back to Gridley in his station wagon. "We were home in five hours,” Tanimoto recalled.

While they were away, a family of Portuguese immigrants intent on helping the family during their ordeal harvested their 1943 peach crop, then leased the farm, Tanimoto said. They kept the Tanimoto’s farm well tended.

Not everyone held in the camps was as fortunate. Many families renting or making mortgage payments lost their homes and properties while imprisoned, Tanimoto said.

For several decades, Tanimoto joined pilgrimages to Tule Lake to rekindle friendships with other former prisoners. His wife, Haruko — also imprisoned at Tule Lake ― accompanied him until her death in 1998.

Months after his release, Tanimoto went back to pick up his then-fiancée, still at Tule Lake. She was released and “we were married at the camp," he said. They were married for 53 years.

Jessica Skropanic is a features reporter for the Record Searchlight/USA Today Network. She covers science, arts, social issues and news stories. Follow her on Twitter @RS_JSkropanic and on Facebook. Join Jessica in the Get Out! Nor Cal recreation Facebook group. To support and sustain this work, please subscribe today. Thank you.

This article originally appeared on Redding Record Searchlight: How America reacted to Pearl Harbor attacks with internment camps