100 years ago Springfield was a union stronghold of the Midwest. Could it be again?

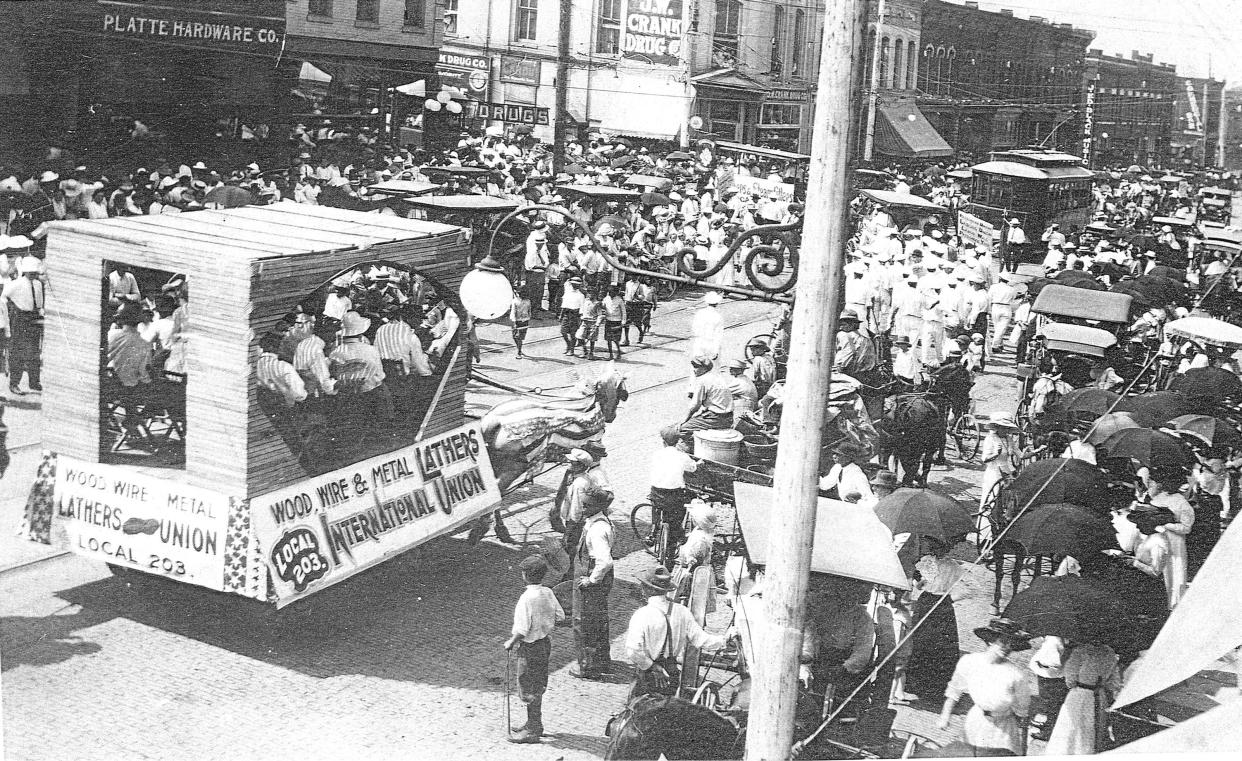

Several years in the first decade of the 20th century an estimated 5,000 unionized laborers marched through the streets of Springfield with reportedly more than 10,000 onlookers cheering them on.

Just over 100 years ago, the decade represented the zenith of labor power in the Queen City of the Ozarks — even rivaling famously powerful unions in Kansas City and St. Louis. But Springfield's history as a labor stronghold in the Midwest has largely faded in the memory of Ozarkers as the latter decades of the 20th century saw the decimation of unions across the United States.

Many Springfield unions organized today were founded in the dawn of last century, said current Springfield Central Labor Council President Justin McCarty — himself a fifth generation laborer in Springfield's Local 178 Plumbers and Pipefitters Union.

"What they fought for then is the same thing we're fighting for now. And that's workers, right? Making sure we have benefits, making sure workers aren't exploited and taken advantage of by unscrupulous business owners. Those are the same fights we fight today," McCarty told the News-Leader just before this year's Labor Day.

"That generation there is the reason why we have the 40 hour workweek, why we have weekends, why there's a retirement structure set up. Those battles were fought in the early 1900s. And we get to enjoy that now. But a hundred years later, we're still trying to advance rights for workers and all our labor organizations are doing is making sure people are protected, that they're getting a fair living wage, and they can be able to provide for their family."

More: Springfield Labor Day parade returns after pandemic absence

When railroads first came to Springfield, so did its first union. In 1871, the city's railroad engineers organized into a union — followed by the city's cigar makers in 1879. At the time, Springfield boasted a population just over 5,000 but it was quickly growing, becoming the state's fifth largest city with more than 20,000 residents by the end of the century.

That time also saw an explosive growth in unionization. By 1892, there were 15 unions in the city, including six unions of the railway trades. Six different assemblies of the Knights of Labor also organized throughout the 1880s, a fraternal order and union that accepted laborers regardless of trade.

At its peak in 1886, Knights counted 1,353 members, including one assembly made up of Black laborers. These numbers made them an influential, if ultimately unsuccessful, block in city politics of the time.

Though never developing long-lasting electoral prowess, labor unions of the time “forced local political and business leaders to accommodate many of the demands of the city’s growing labor movement," according to Missouri State University History professor Stephen McIntyre in his article "'The City Belongs to the Local Unions: The Rise of the Springfield Labor Movement, 1871-1912."

At the time, unionists and their allies were concentrated in North Springfield, where the railway lines met the city and poverty was concentrated, as it remains so today.

By 1887, unions were putting forward their own candidates in local elections — running on a platform of an 8-hour workday for municipal employees, minimum wage laws, and increased funding for education and welfare.

Most of these candidates lost by a wide margin, but labor came closest to having a voice on city council in 1888 when labor's candidate came second in a three-way race with 34 percent of the vote in a northern ward of the city. That same year, labor narrowly won a citywide race for Springfield Assessor, running under the banner of the United Labor Party. Unlike today, Springfield municipal elections were then partisan.

In that race, Republicans nominated African-American J.H. McCracken and Democrats failed to run a candidate. Railroad engineer John Barry was able to coalesce opposition to Republicans and defeated McCracken in a 260 vote margin.

The 1890s saw a great decline of unionism in Springfield — beginning the decade with 16 unions and falling to just two by its end. But with the Progressive Movement fully in swing by the new century, labor unions saw a great resurgence across America in the early 1900s.

More: Springfield Starbucks votes to unionize amid nationwide labor movement, first in region

There were 32 unions and more than 2,000 unionized workers in the city by 1902. The quick growth led to renewed local influence and the massive Labor Day parades seen throughout the decade — the national holiday itself only little more than a decade old.

At the time, unionists organized in Springfield under the Socialist Party, which had recently formed under the leadership of famous union organizer Eugene Debs — who visited Springfield several times in the 1900s. Under the socialist banner, Debs infamously ran for president five times, even once in the confines of jail for his opposition to American involvement in World War I.

Perhaps because of the socialist label, the Socialist Party struggled electorally in Springfield — never polling above 10 percent in the decade's elections. But their presence as a spoiler made their voters highly sought after by the two major parties, who were loath to anger the union vote.

During depression of 1907, labor and socialists pressured the city to hire the unemployed to work on city streets. The day after the demand was made, Springfield city council voted to hire 100 such workers. Upon the creation of a new city charter in 1910, a provision was added mandating an 8-hour work day maximum for city employees and those who contracted with the city.

According to McCarty, there were more than 50 different unions in Springfield at the time. But such labor power did not last.

“Union membership continued to grow all the way up until the '70s. But when businesses changed their practices and started doing more union busting, there was a long decline in union membership across the country and in Springfield,” McCarty told the News-Leader. “But I think people are starting to realize that when they stand up for each other and look out for their brother and their sister instead of just themselves, it helps everybody.”

But McCarty sees a reassurance of labor power in Springfield, pointing to the recent unionization of a Springfield Starbucks and an affinity for unions among young people not seen in the previous generation.

"The newest generation of workers are looking out for everybody and not themselves. It makes me proud. They are not trying to step on the backs of other people to get up the corporate ladder,” he said. “Those Starbucks workers took their future into their own hands and I’m very encouraged by that.”

The Springfield Central Labor Council has no intent to run candidates like their forbearers did a century ago, but they do hope to increase heir influence with city government and change city policy. A current priority is for the city to enact a local preference for contractors and builders who receive city contracts or funds.

"We've outsourced in our community and dollars are going elsewhere. We need tax money going toward local providers,” McCarty said. “Then there’s what we’ve always fought for — higher wages. We need to ensure that people are making not a minimum wage, but a living wage where they're not bound to their employer like an indentured servant for the rest of their life. Where workers can have a life of their own."

Andrew Sullender is the local government reporter for the Springfield News-Leader. Follow him on Twitter @andrewsullender. Email tips and story ideas to asullender@gannett.com.

This article originally appeared on Springfield News-Leader: Could Springfield be a union stronghold of the Midwest again?